Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers▲ | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

03 Jul 2020

The 'Noble false widow' spider Steatoda nobilis is an emerging public health and ecological threatHambler, C. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/axbd4How the noble false widow spider Steatoda nobilis can turn out to be a rising public health and ecological concernRecommended by Etienne Bilgo based on reviews by Michel Dugon and 2 anonymous reviewers"The noble false widow spider Steatoda nobilis is an emerging public health and ecological threat" by Clive Hambler (2020) is an appealing article discussing important aspects of the ecology and distribution of a medically significant spider, and the health concerns it raises. References [1] Hambler, C. (2020). The “Noble false widow” spider Steatoda nobilis is an emerging public health and ecological threat. OSF Preprints, axbd4, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. doi: 10.31219/osf.io/axbd4 | The 'Noble false widow' spider Steatoda nobilis is an emerging public health and ecological threat | Hambler, C. | <p>*Steatoda nobilis*, the 'Noble false widow' spider, has undergone massive population growth in southern Britain and Ireland, at least since 1990. It is greatly under-recorded in Britain and possibly globally. Now often the dominant spider on an... |  | Arachnids, Behavior, Biogeography, Biological invasions, Conservation biology, Demography/population dynamics, Ecology, Medical entomology, Methodology, Pest management, Toxicology, Veterinary entomology | Etienne Bilgo | 2019-06-28 18:26:05 | View | |

10 Jan 2020

Culex saltanensis and Culex interfor (Diptera: Culicidae) are susceptible and competent to transmit St. Louis encephalitis virus (Flavivirus: Flaviviridae) in central ArgentinaBeranek MD, Quaglia AI, Peralta GC, Flores FS, Stein M, Diaz LA, Almirón WR and Contigiani MS https://doi.org/10.1101/722579Multiple vector species may be responsible for transmission of Saint Louis Encephalatis Virus in ArgentinaRecommended by Anna Cohuet based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersMedical and veterinary entomology is a discipline that deals with the role of insects on human and animal health. A primary objective is the identification of vectors that transmit pathogens. This is the aim of Beranek and co-authors in their study [1]. They focus on mosquito vector species responsible for transmission of St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV), an arbovirus that circulates in avian species but can incidentally occur in dead end mammal hosts such as humans, inducing symptoms and sometimes fatalities. Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus is known as the most common vector, but other species are suspected to also participate in transmission. Among them Culex saltanensis and Culex interfor have been found to be infected by the virus in the context of outbreaks. The fact that field collected mosquitoes carry virus particles is not evidence for their vector competence: indeed to be a competent vector, the mosquito must not only carry the virus, but also the virus must be able to replicate within the vector, overcome multiple barriers (until the salivary glands) and be present at sufficient titre within the saliva. This paper describes the experiments implemented to evaluate the vector competence of Cx. saltanensis and Cx. interfor from ingestion of SLEV to release within the saliva. Females emerged from field-collected eggs of Cx. pipiens quinquefasciatus, Cx. saltanensis and Cx. interfor were allowed to feed on SLEV infected chicks and viral development was measured by using (i) the infection rate (presence/absence of virus in the mosquito abdomen), (ii) the dissemination rate (presence/absence of virus in mosquito legs), and (iii) the transmission rate (presence/absence of virus in mosquito saliva). The sample size for each species is limited because of difficulties for collecting, feeding and maintaining large numbers of individuals from field populations, however the results are sufficient to show that this strain of SLEV is able to disseminate and be expelled in the saliva of mosquitoes of the three species at similar viral loads. This work therefore provides evidence that Cx saltanensis and Cx interfor are competent species for SLEV to complete its life-cycle. Vector competence does not directly correlate with the ability to transmit in real life as the actual vectorial capacity also depends on the contact between the infectious vertebrate hosts, the mosquito life expectancy and the extrinsic incubation period of the viruses. The present study does not deal with these characteristics, which remain to be investigated to complete the picture of the role of Cx saltanensis and Cx interfor in SLEV transmission. However, this study provides proof of principle that that SLEV can complete it’s life-cycle in Cx saltanensis and Cx interfor. Combined with previous knowledge on their feeding preference, this highlights their potential role as bridge vectors between birds and mammals. These results have important implications for epidemiological forecasting and disease management. Public health strategies should consider the diversity of vectors in surveillance and control of SLEV. References | Culex saltanensis and Culex interfor (Diptera: Culicidae) are susceptible and competent to transmit St. Louis encephalitis virus (Flavivirus: Flaviviridae) in central Argentina | Beranek MD, Quaglia AI, Peralta GC, Flores FS, Stein M, Diaz LA, Almirón WR and Contigiani MS | <p>Infectious diseases caused by mosquito-borne viruses constitute health and economic problems worldwide. St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV) is endemic and autochthonous in the American continent. Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus is the primary ur... |  | Medical entomology | Anna Cohuet | 2019-08-03 00:56:38 | View | |

22 Jul 2020

The open bar is closed: restructuration of a native parasitoid community following successful control of an invasive pest.David Muru, Nicolas Borowiec, Marcel Thaon, Nicolas Ris, Madalina Ionela Viciriuc, Sylvie Warot, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.20.884908Raise and fall of an invasive pest and consequences for native parasitoid communitiesRecommended by Stefaniya Kamenova based on reviews by Kévin Tougeron and Miguel González Ximénez de EmbúnHost-parasitoid interactions have been the focus of extensive ecological research for decades. One the of the major reasons is the importance host-parasitoid interactions play for the biological control of crop pests. Parasitoids are the main natural regulators for a large number of economically important pest insects, and in many cases they could be the only viable crop protection strategy. Parasitoids are also integral part of complex food webs whose structure and diversity display large spatio-temporal variations [1-3]. With the increasing globalization of human activities, the generalized spread and establishment of invasive species is a major cause of disruption in local community and food web spatio-temporal dynamics. In particular, the deliberate introduction of non-native parasitoids as part of biological control programs, aiming the suppression of established, and also highly invasive crop pests, is a common practice with potentially significant, yet poorly understood effects on local food web dynamics (e.g. [4]). References [1] Eveleigh ES, McCann KS, McCarthy PC, Pollock SJ, Lucarotti CJ, Morin B, McDougall GA, Strongman DB, Huber JT, Umbanhowar J, Faria LDB (2007). Fluctuations in density of an outbreak species drive diversity cascades in food webs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 16976-16981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704301104 | The open bar is closed: restructuration of a native parasitoid community following successful control of an invasive pest. | David Muru, Nicolas Borowiec, Marcel Thaon, Nicolas Ris, Madalina Ionela Viciriuc, Sylvie Warot, Elodie Vercken | <p>The rise of the Asian chestnut gall wasp *Dryocosmus kuriphilus* in France has benefited the native community of parasitoids originally associated with oak gall wasps by becoming an additional trophic subsidy and therefore perturbing population... |  | Biocontrol, Biological invasions, Ecology, Insecta | Stefaniya Kamenova | 2019-12-31 09:08:49 | View | |

24 Jun 2022

Dopamine pathway characterization during the reproductive mode switch in the pea aphidGaël Le Trionnaire, Sylvie Hudaverdian, Gautier Richard, Sylvie Tanguy, Florence Gleonnec, Nathalie Prunier-Leterme, Jean-Pierre Gauthier, Denis Tagu https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.10.984989In search of the links between environmental signals and polyphenismRecommended by Mathieu Joron based on reviews by Antonia Monteiro and 2 anonymous reviewersPolyphenisms offer an opportunity to study the links between phenotype, development, and environment in a controlled genomic context (Simpson, Sword, & Lo, 2011). In organisms with short generation times, individuals living and developing in different seasons encounter different environmental conditions. Adaptive plasticity allows them to express different phenotypes in response to seasonal cues, such as temperature or photoperiod. Such phenotypes can be morphological variants, for instance displaying different wing patterns as seen in butterflies (Brakefield & Larsen, 1984; Nijhout, 1991; Windig, 1999), or physiological variants, characterized for instance by direct development vs winter diapause in temperate insects (Dalin & Nylin, 2012; Lindestad, Wheat, Nylin, & Gotthard, 2019; Shearer et al., 2016). Many aphids display cyclical parthenogenesis, a remarkable seasonal polyphenism for reproductive mode (Tagu, Sabater-Muñoz, & Simon, 2005), also sometimes coupled with wing polyphenism (Braendle, Friebe, Caillaud, & Stern, 2005), which allows them to switch between parthenogenesis during spring and summer to sexual reproduction and the production of diapausing eggs before winter. In the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum, photoperiod shortening results in the production, by parthenogenetic females, of embryos developing into the parthenogenetic mothers of sexual individuals. The link between parthenogenetic reproduction and sexual reproduction, therefore, occurs over two generations, changing from a parthenogenetic form producing parthenogenetic females (virginoparae), to a parthenogenetic form producing sexual offspring (sexuparae), and finally sexual forms producing overwintering eggs (Le Trionnaire et al., 2022). The molecular basis for the transduction of the environmental signal into reproductive changes is still unknown, but the dopamine pathway is an interesting candidate. Form-specific expression of certain genes in the dopamine pathway occurs downstream of the perception of the seasonal cue, notably with a marked decrease in the heads of embryos reared under short-day conditions and destined to become sexuparae. Dopamine has multiple roles during development, with one mode of action in cuticle melanization and sclerotization, and a neurological role as a synaptic neurotransmitter. Both modes of action might be envisioned to contribute functionally to the perception and transduction of environmental signals. In this study, Le Trionnaire and colleagues aim at clarifying this role in the pea aphid (Le Trionnaire et al., 2022). Using quantitative RT-PCR, RNA-seq, and in situ hybridization of RNA probes, they surveyed the timing and spatial patterns of expression of dopamine pathway genes during the development of different stages of embryo to larvae reared under long and short-day conditions, and destined to become virginoparae or sexuparae females, respectively. The genes involved in the synaptic release of dopamine generally did not show differences in expression between photoperiodic treatments. By contrast, pale and ddc, two genes acting upstream of dopamine production, generally tended to show a downregulation in sexuparare embryo, as well as genes involved in cuticle development and interacting with the dopamine pathway. The downregulation of dopamine pathway genes observed in the heads of sexuparare juveniles is already detectable at the embryonic stage, suggesting embryos might be sensing environmental cues leading them to differentiate into sexuparae females. The way pale and ddc expression differences could influence environmental sensitivity is still unclear. The results suggest that a cuticle phenotype specifically in the heads of larvae could be explored, perhaps in the form of a reduction in cuticle sclerotization and melanization which might allow photoperiod shortening to be perceived and act on development. Although its causality might be either way, such a link would be exciting to investigate, yet the existence of cuticle differences between the two reproductive types is still a hypothesis to be tested. The lack of differences in the expression of synaptic release genes for dopamine might seem to indicate that the plastic response to photoperiod is not mediated via neurological roles. Yet, this does not rule out the role of decreasing levels of dopamine in mediating this response in the central nervous system of embryos, even if the genes regulating synaptic release are equally expressed. To test for a direct role of ddc in regulating the reproductive fate of embryos, the authors have generated CrispR-Cas9 knockout mutants. Those mutants displayed egg cuticle melanization, but with lethal effects, precluding testing the effect of ddc at later stages in development. Gene manipulation becomes feasible in the pea aphid, opening up certain avenues for understanding the roles of other genes during development. This study adds nicely to our understanding of the intricate changes in gene expression involved in polyphenism. But it also shows the complexity of deciphering the links between environmental perception and changes in physiology, which mobilise multiple interacting gene networks. In the era of manipulative genetics, this study also stresses the importance of understanding the traits and phenotypes affected by individual genes, which now seems essential to piece the puzzle together. References Braendle C, Friebe I, Caillaud MC, Stern DL (2005) Genetic variation for an aphid wing polyphenism is genetically linked to a naturally occurring wing polymorphism. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 272, 657–664. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2004.2995 Brakefield PM, Larsen TB (1984) The evolutionary significance of dry and wet season forms in some tropical butterflies. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 22, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.1984.tb00795.x Dalin P, Nylin S (2012) Host-plant quality adaptively affects the diapause threshold: evidence from leaf beetles in willow plantations. Ecological Entomology, 37, 490–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2311.2012.01387.x Le Trionnaire G, Hudaverdian S, Richard G, Tanguy S, Gleonnec F, Prunier-Leterme N, Gauthier J-P, Tagu D (2022) Dopamine pathway characterization during the reproductive mode switch in the pea aphid. bioRxiv, 2020.03.10.984989, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.10.984989 Lindestad O, Wheat CW, Nylin S, Gotthard K (2019) Local adaptation of photoperiodic plasticity maintains life cycle variation within latitudes in a butterfly. Ecology, 100, e02550. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2550 Nijhout HF (1991). The development and evolution of butterfly wing patterns. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. Shearer PW, West JD, Walton VM, Brown PH, Svetec N, Chiu JC (2016) Seasonal cues induce phenotypic plasticity of Drosophila suzukii to enhance winter survival. BMC Ecology, 16, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-016-0070-3 Simpson SJ, Sword GA, Lo N (2011) Polyphenism in Insects. Current Biology, 21, R738–R749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.006 Tagu D, Sabater-Muñoz B, Simon J-C (2005) Deciphering reproductive polyphenism in aphids. Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, 48, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2005.9652172 Windig JJ (1999) Trade-offs between melanization, development time and adult size in Inachis io and Araschnia levana (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae)? Heredity, 82, 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6884510 | Dopamine pathway characterization during the reproductive mode switch in the pea aphid | Gaël Le Trionnaire, Sylvie Hudaverdian, Gautier Richard, Sylvie Tanguy, Florence Gleonnec, Nathalie Prunier-Leterme, Jean-Pierre Gauthier, Denis Tagu | <p>Aphids are major pests of most of the crops worldwide. Such a success is largely explained by the remarkable plasticity of their reproductive mode. They reproduce efficiently by viviparous parthenogenesis during spring and summer generating imp... |  | Development, Genetics/Genomics, Insecta, Molecular biology | Mathieu Joron | 2020-03-13 13:01:44 | View | |

05 Jan 2021

Do substrate roughness and gap distance impact gap-bridging strategies in arboreal chameleons?Allison M. Luger, Vincent Vermeylen, Anthony Herrel, Dominique Adriaens https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.260596Gap-bridging strategies in arboreal chameleonsRecommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Simon Baeckens and 2 anonymous reviewersUntil now, very little is known about the tail use and functional performance in tail prehensile animals. Luger et al. (2020) are the first to provide explorative observations on trait related modulation of tail use, despite the lack of a sufficiently standardized data set to allow statistical testing. They described whether gap distance, perch diameter, and perch roughness influence tail use and overall locomotor behavior of the species Chamaeleo calyptratus. References Luger, A.M., Vermeylen, V., Herrel, A. and Adriaens, D. (2020) Do substrate roughness and gap distance impact gap-bridging strategies in arboreal chameleons? bioRxiv, 2020.08.21.260596, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.260596 | Do substrate roughness and gap distance impact gap-bridging strategies in arboreal chameleons? | Allison M. Luger, Vincent Vermeylen, Anthony Herrel, Dominique Adriaens | <p>Chameleons are well-equipped for an arboreal lifestyle, having ‘zygodactylous’ hands and feet as well as a fully prehensile tail. However, to what degree tail use is preferred over autopod prehension has been largely neglected. Using an indoor ... |  | Behavior, Biology, Herpetology, Reptiles, Vertebrates | Ellen Decaestecker | 2020-08-25 10:06:42 | View | |

28 Apr 2021

Inference of the worldwide invasion routes of the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus using approximate Bayesian computation analysisSophie Mallez, Chantal Castagnone, Eric Lombaert, Philippe Castagnone-Sereno, Thomas Guillemaud https://doi.org/10.1101/452326Extracting the maximum historical information on pine wood nematode worldwide invasion from genetic dataRecommended by Stéphane Dupas based on reviews by Aude Gilabert and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Aude Gilabert and 1 anonymous reviewer

Redistribution of domesticated and non domesticated species by humans profoundly affected earth biogeography and in return human activities. This process accelerated exponentially since human expansion out of Africa, leading to the modern global, highly connected and homogenized, agriculture and trade system (Mack et al. 2000, Jaksic and Castro 2021), that threatens biological diversity and genetic resources. To accompany quarantine and control effort, the reconstruction of invasion routes provides valuable information that help identifying critical nodes and edges in the global networks (Estoup and Guillemaud 2010, Cristescu 2015). Historical records and genetic markers are the two major sources of information of this corpus of knowledge on Anthropocene historical phylogeography. With the advances of molecular genetics tools, the genealogy of these introductions events could be revisited and empowered. Due to their idiosyncrasy and intimate association with the contingency of human trades and activities, understanding the invasion and domestication routes require particular statistical tools (Fraimout et al. 2017). Because it encompasses all these theoretical, ecological and economical implications, I am pleased to recommend the readers of PCI Zoology this article by Mallez et al. (2021) on pine wood nematode invasion route inference from genetic markers using Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) methods. Economically and ecologically, this pest, is responsible for killing millions of pines worldwide each year. The results show these damages and the global genetic patterns are due to few events of successful introductions. The authors consider that this low probability of introductions success reinforces the idea that quarantine measures are efficient. This is illustrated in Europe where the pine-worm has been quarantined successfully in the Iberian Peninsula since 1999. Another relevant conclusion is that hybridization between invasive populations have not been observed and implied in the invasion process. Finally the present study reinforced the role of Asiatic bridgehead populations in invasion process including in Europe. Methodologically, for the first time, ABC was applied to this species. A total of 310 individual sequences were added to the Mallez et al. (2015) microsatellite dataset. Fraimoult et al. (2017) showed the interest to apply random forest to improve scenario selection in ABC framework. This method, implemented in the DiYABC software (Collin et al. 2020) for invasion route scenario selection allows to handle more complex scenario alternatives and was used in this study. In this article by Mallez et al. (2021), you will also find a clear illustration of the step-by-step approach to select scenario using ABC techniques (Lombaert et al. 2014). The rationale is to reduce number of scenario to be tested by assuming that most recent invasions cannot be the source of the most ancient invasions and to use posterior results on most ancient routes as prior hypothesis to distinguish following invasions. The other simplification is to perform classical population genetic analysis to characterize genetic units and representative populations prior to invasion routes scenarios selection by ABC. Yet, even when using the most advanced Bayesian inference methods, it is recognized by the authors that the method can be pushed to its statistical power limits. The method is appropriate when population show strong inter-population genetic structure. But the high number of differentiated populations in native area can be problematic since it is generally associated to incomplete sampling scheme. The hypothesis of ghost populations source allowed to bypass this difficulty, but the authors consider simulation studies are needed to assess the joint effect of genetic diversity and number of genetic markers on the inference results in such situation. Also the need to use a stepwise approach to reduce the number of scenario to test has to be considered with caution. Scenarios that are not selected but have non negligible posterior, cannot be ruled out in the constitution of next step scenarios hypotheses. Due to its interest to understand this major facet of Anthropocene, reconstruction of invasion routes should be more considered as a guide to damper biological homogenization process. References Collin, F.-D., Durif, G., Raynal, L., Lombaert, E., Gautier, M., Vitalis, R., Marin, J.-M. and Estoup, A. (2020) Extending Approximate Bayesian Computation with Supervised Machine Learning to infer demographic history from genetic polymorphisms using DIYABC Random Forest. Authorea. doi: https://doi.org/10.22541/au.159480722.26357192 Cristescu, M.E. (2015) Genetic reconstructions of invasion history. Molecular Ecology, 24, 2212–2225. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.13117 Estoup, A. and Guillemaud, T., (2010) Reconstructing routes of invasion using genetic data: Why, how and so what? Molecular Ecology, 9, 4113-4130. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04773.x Fraimout, A., Debat, V., Fellous, S., Hufbauer, R.A., Foucaud, J., Pudlo, P., Marin, J.M., Price, D.K., Cattel, J., Chen, X., Deprá, M., Duyck, P.F., Guedot, C., Kenis, M., Kimura, M.T., Loeb, G., Loiseau, A., Martinez-Sañudo, I., Pascual, M., Richmond, M.P., Shearer, P., Singh, N., Tamura, K., Xuéreb, A., Zhang, J., Estoup, A. and Nielsen, R. (2017) Deciphering the routes of invasion of Drosophila suzukii by Means of ABC Random Forest. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 34, 980-996. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msx050 Jaksic, F.M. and Castro, S.A. (2021). Biological Invasions in the Anthropocene, in: Jaksic, F.M., Castro, S.A. (Eds.), Biological Invasions in the South American Anthropocene: Global Causes and Local Impacts. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 19-47. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56379-0_2 Lombaert, E., Guillemaud, T., Lundgren, J., Koch, R., Facon, B., Grez, A., Loomans, A., Malausa, T., Nedved, O., Rhule, E., Staverlokk, A., Steenberg, T. and Estoup, A. (2014) Complementarity of statistical treatments to reconstruct worldwide routes of invasion: The case of the Asian ladybird Harmonia axyridis. Molecular Ecology, 23, 5979-5997. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12989 Mack, R.N., Simberloff, D., Lonsdale, M.W., Evans, H., Clout, M., Bazzaz, F.A. (2000) Biotic Invasions : Causes , Epidemiology , Global Consequences , and Control. Ecological Applications, 10, 689-710. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[0689:BICEGC]2.0.CO;2 Mallez, S., Castagnone, C., Lombaert, E., Castagnone-Sereno, P. and Guillemaud, T. (2021) Inference of the worldwide invasion routes of the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus using approximate Bayesian computation analysis. bioRxiv, 452326, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Zoology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/452326 | Inference of the worldwide invasion routes of the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus using approximate Bayesian computation analysis | Sophie Mallez, Chantal Castagnone, Eric Lombaert, Philippe Castagnone-Sereno, Thomas Guillemaud | <p>Population genetics have been greatly beneficial to improve knowledge about biological invasions. Model-based genetic inference methods, such as approximate Bayesian computation (ABC), have brought this improvement to a higher level and are now... |  | Biogeography, Biological invasions, Ecology, Evolution, Genetics/Genomics, Herbivores, Invertebrates, Molecular biology, Nematology | Stéphane Dupas | 2020-09-15 10:59:41 | View | |

09 Jul 2021

First detection of herpesvirus and mycoplasma in free-ranging Hermann tortoises (Testudo hermanni), and in potential pet vectorsJean-marie Ballouard, Xavier Bonnet, Julie Jourdan, Albert Martinez-Silvestre, Stephane Gagno, Brieuc Fertard, Sebastien Caron https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.22.427726Welfare threatened speciesRecommended by Peter Galbusera based on reviews by Francis Vercammen and Maria Luisa MarenzoniWildlife is increasingly threatened by drops in number of individuals and populations, and eventually by extinction. Besides loss of habitat, persecution, pet trade,… a decrease in individual health status is an important factor to consider. In this article, Ballouard et al (2021) perform a thorough analysis on the prevalence of two pathogens (herpes virus and mycoplasma) in (mainly) Western Hermann’s tortoises in south-east France. This endangered species was suspected to suffer from infections obtained through released/escaped pet tortoises. By incorporating samples of captive as well as wild tortoises, they convincingly confirm this and identify some possible ‘pet’ vectors. In February this year, a review paper on health assessments in wildlife was published (Kophamel et al 2021). Amongst others, it shows reptilia/chelonia are relatively well-represented among publications. It also contains a useful conceptual framework, in order to improve the quality of the assessments to better facilitate conservation planning. The recommended manuscript (Ballouard et al 2021) adheres to many aspects of this framework (e.g. minimum sample size, risk status, …) while others might need more (future) attention. For example, climate/environmental changes are likely to increase stress levels, which could lead to more disease symptoms. So, follow-up studies should consider conducting endocrinological investigations to estimate/monitor stress levels. Kophamel et al (2021) also stress the importance of strategic international collaboration, which may allow more testing of Eastern Hermann’s Tortoise, as these were shown to be infected by mycoplasma. The genetic health of individuals/populations shouldn’t be forgotten in health/stress assessments. As noted by Ballouard et al (2021), threatened species often have low genetic diversity which makes them more vulnerable to diseases. So, it would be interesting to link the infection data with (individual) genetic characteristics. In future research, the samples collected for this paper could fit that purpose. Finally, it is expected that this paper will contribute to the conservation management strategy of the Hermann’s tortoises. As such, it will be interesting to see how the results of the current paper will be implemented in the ‘field’. As the infections are likely caused by releases/escaped pets and as treating the wild animals is difficult, preventing them from getting infected through pets seems a priority. Awareness building among pet holders and monitoring/treating pets should be highly effective. References Ballouard J-M, Bonnet X, Jourdan J, Martinez-Silvestre A, Gagno S, Fertard B, Caron S (2021) First detection of herpesvirus and mycoplasma in free-ranging Hermann’s tortoises (Testudo hermanni), and in potential pet vectors. bioRxiv, 2021.01.22.427726, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.22.427726 Kophamel S, Illing B, Ariel E, Difalco M, Skerratt LF, Hamann M, Ward LC, Méndez D, Munns SL (2021), Importance of health assessments for conservation in noncaptive wildlife. Conservation Biology. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13724 | First detection of herpesvirus and mycoplasma in free-ranging Hermann tortoises (Testudo hermanni), and in potential pet vectors | Jean-marie Ballouard, Xavier Bonnet, Julie Jourdan, Albert Martinez-Silvestre, Stephane Gagno, Brieuc Fertard, Sebastien Caron | <p style="text-align: justify;">Two types of pathogens cause highly contagious upper respiratory tract diseases (URTD) in Chelonians: testudinid herpesviruses (TeHV) and a mycoplasma (<em>Mycoplasma agassizii</em>). In captivity, these infections ... | Parasitology, Reptiles | Peter Galbusera | 2021-01-25 17:25:34 | View | ||

26 Apr 2023

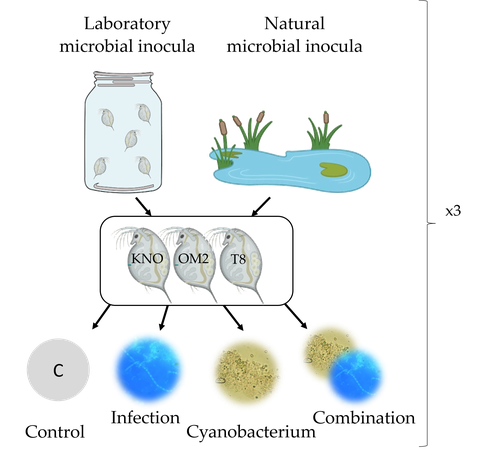

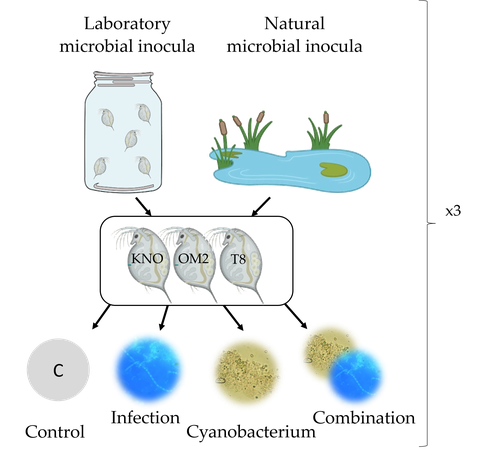

Microbiome mediated tolerance to biotic stressors: a case study of the interaction between a toxic cyanobacterium and an oomycete-like infection in Daphnia magnaShira Houwenhuyse*, Lore Bulteel*, Isabel Vanoverberghe, Anna Krzynowek, Naina Goel, Manon Coone, Silke Van den Wyngaert, Arne Sinnesael, Robby Stoks & Ellen Decaestecker https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/9n4mgMulti-stress responses depend on the microbiome in the planktonic crustacean DaphniaRecommended by Bertanne Visser and Mathilde Scheifler based on reviews by Natacha Kremer and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Natacha Kremer and 2 anonymous reviewers

The critical role that gut microbiota play in many aspects of an animal’s life, including pathogen resistance, detoxification, digestion, and nutritional physiology, is becoming more and more apparent (Engel and Moran 2013; Lindsay et al., 2020). Gut microbiota recruitment and maintenance can be largely affected by the surrounding environment (Chandler et al., 2011; Callens et al., 2020). The environment may thus dictate gut microbiota composition and diversity, which in turn can affect organismal responses to stress. Only few studies have, however, taken the gut microbiota into account to estimate life histories in response to multiple stressors in aquatic systems (Macke et al., 2016). Houwenhuyse et al., investigate how the microbiome affects life histories in response to ecologically relevant single and multiple biotic stressors (an oomycete-like parasite, and a toxic cyanobacterium) in Daphnia magna (Houwenhuyse et al., 2023). Daphnia is an excellent model, because this aquatic system lends itself extremely well for gut microbiota transplantation and manipulation. This is due to the possibility to sterilize eggs (making them free of bacteria), horizontal transmission of bacteria from the environment, and the relative ease of culturing genetically similar Daphnia clones in large numbers. The authors use an elegant experimental design to show that the Daphnia gut microbial community differs when derived from a laboratory versus natural inoculum, the latter being more diverse. The authors subsequently show that key life history traits (survival, fecundity, and body size) depend on the stressors (and combination thereof), the microbiota (structure and diversity), and Daphnia genotype. A key finding is that Daphnia exposed to both biotic stressors show an antagonistic interaction effect on survival (being higher), but only in individuals containing laboratory gut microbiota. The exact mechanism remains to be determined, but the authors propose several interesting hypotheses as to why Daphnia with more diverse gut microbiota do less well. This could be due, for example, to increased inter-microbe competition or an increased chance of contracting opportunistic, parasitic bacteria. For Daphnia with less diverse laboratory gut microbiota, a monopolizing species may be particularly beneficial for stress tolerance. Alongside these interesting findings, the paper also provides extensive information about the gut microbiota composition (available in the supplementary files), which is a very useful resource for other researchers. Overall, this study reveals that multiple, interacting factors affect the performance of Daphnia under stressful conditions. Of importance is that laboratory studies may be based on simpler microbiota systems, meaning that stress responses measured in the laboratory may not accurately reflect what is happening in nature. REFERENCES Callens M, De Meester L, Muylaert K, Mukherjee S, Decaestecker E. The bacterioplankton community composition and a host genotype dependent occurrence of taxa shape the Daphnia magna gut bacterial community. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2020;96(8):fiaa128. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiaa128 Chandler JA, Lang JM, Bhatnagar S, Eisen JA, Kopp A. Bacterial communities of diverse Drosophila species: ecological context of a host-microbe model system. PLOS Genetics. 2011;7(9):e1002272. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002272 Engel P, Moran NA. The gut microbiota of insects - diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2013;37(5):699-735. https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6976.12025 Houwenhuyse S, Bulteel L, Vanoverberghe I, Krzynowek A, Goel N et al. Microbiome mediated tolerance to biotic stressors: a case study of the interaction between a toxic cyanobacterium and an oomycete-like infection in Daphnia magna. 2023. OSF, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/9n4mg Lindsay EC, Metcalfe NB, Llewellyn MS. The potential role of the gut microbiota in shaping host energetics and metabolic rate. Journal of Animal Ecology. 2020;89(11):2415-2426. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13327 Macke E, Tasiemski A, Massol F, Callens M, Decaestecker E. Life history and eco-evolutionary dynamics in light of the gut microbiota. Oikos. 2017;126(4):508-531. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.03900 | Microbiome mediated tolerance to biotic stressors: a case study of the interaction between a toxic cyanobacterium and an oomycete-like infection in *Daphnia magna* | Shira Houwenhuyse*, Lore Bulteel*, Isabel Vanoverberghe, Anna Krzynowek, Naina Goel, Manon Coone, Silke Van den Wyngaert, Arne Sinnesael, Robby Stoks & Ellen Decaestecker | <p style="text-align: justify;">Organisms are increasingly facing multiple, potentially interacting stressors in natural populations. The ability of populations coping with combined stressors depends on their tolerance to individual stressors and ... |  | Aquatic, Biology, Crustacea, Ecology, Life histories, Symbiosis | Bertanne Visser | 2021-05-17 16:18:18 | View | |

08 Feb 2022

The initial response of females towards congeneric males matches the propensity to hybridise in OphthalmotilapiaMaarten Van Steenberge, Noemie Jublier, Loic Kever, Sophie Gresham, Sofie Derycke, Jos Snoeks, Eric Parmentier, Pascal Poncin, Erik Verheyen https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.07.455508Experimental evidence for asymmetrical species recognition in East African Ophthalmotilapia cichlidsRecommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by George Turner and 2 anonymous reviewersI recommend the Van Steenberge et al. study. With over 2000 endemic species, the East African cichlids are a well-established model system in speciation research (Salzburger 2018) and several models have been proposed and tested to explain how these radiations formed (Kocher 2004). Hybridization was shown to be a main driver of the rapid speciation and adaptive radiations of the East African Cichlid fishes (Seehausen 2004). However, it is obvious that unrestrained hybridization also has the potential to reduce taxonomic diversity by erasing species barriers. In the classical model of cichlid evolution, special emphasis was placed on mate preference (Kocher 2004). However, no attention was placed on species recognition, which was implicitly assumed. There is, however, more research needed on what species recognition means, especially in radiating lineages such as cichlids. In a previous study, Nevado et al. 2011 found traces of asymmetrical hybridization between members of the Lake Tanganyika radiation: the genus Ophthalmotilapia. This recommended study by Van Steenberge et al. is based on Nevado et al. (2011), which detected that in one genus of Ophthalmotilapia mitochondrial DNA ‘typical’ for one of the four species (O. nasuta) was also found in three other species (O. ventralis, O. heterodonta, and O. boops). The authors suggested that this could be explained by the fact that females of the three other species accepted O. nasuta males, but that O. nasuta females were more selective and accepted only conspecifc males. This could hence be due to asymmetric mate preferences, or by asymmetric abilities for species recognition. This is exactly what the current study by Van Steenberge et al. did. They tested the latter hypothesis by presenting females of two different Ophthalmotilapia species with con- and heterospecific males. This was tested through experiments, making use of wild specimens of two species: O. nasuta and O. ventralis. The authors assumed that if they performed classical “choice-experiments”, they would not notice the recognition effects, given that females would just select preferred, most likely conspecific, males. Instead, specimens were only briefly presented to other fishes since the authors wanted to compare differences in the ability for ‘species recognition’. In this, the authors followed Mendelson and Shaw (2012) who used “a measurable difference in behavioural response towards conspecifics as compared to heterospecifics’’ as a definition for recognition. Instead of the focus on selection/preference, they investigated if females of different species behaved differently, and hence detected the difference between conspecific and heterospecific males. This was tested by a short (15 minutes) exposure to another fish in an isolated part of the aquarium. Recognition was defined as the ‘difference in a particular behaviour between the two conditions’. What was monitored was the swimming behaviour and trajectory (1 image per second) together with known social behaviours of this genus. The selection of these behaviours was further facilitated based on experimental set-ups of reproductive behaviour or the same species previously described by the same research team (Kéver et al. 2018). The result was that O. nasuta females, for which it was expected that they would not hybridize, showed a different behaviour towards a con- or a heterospecific male. They interacted less with males of the other species. What was unexpected is that there was no difference in behaviour of the females whether they recognized a male or (control) female of their own species. This suggests that they did not detect differences in reproductive behaviour, but rather in the interactions between conspecifics. For females of O. ventralis, for which there are indications for hybridization in the wild, they did not find a difference in behaviour. Females of this species behaved identically with respect to the right and wrong males as well as towards the control females. Interestingly is thus that a complex pattern between species in the wild could be (partially) explained by the behaviour/interaction at first impression of the individuals of these species. References Kéver L, Parmentier E, Derycke S, Verheyen E, Snoeks J, Van Steenberge M, Poncin P (2018) Limited possibilities for prezygotic barriers in the reproductive behaviour of sympatric Ophthalmotilapia species (Teleostei, Cichlidae). Zoology, 126, 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zool.2017.12.001 Kocher TD (2004) Adaptive evolution and explosive speciation: the cichlid fish model. Nature Reviews Genetics, 5, 288–298. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg1316 Mendelson TC, Shaw KL (2012) The (mis)concept of species recognition. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 27, 421–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2012.04.001 Nevado B, Fazalova V, Backeljau T, Hanssens M, Verheyen E (2011) Repeated Unidirectional Introgression of Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA Between Four Congeneric Tanganyikan Cichlids. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 28, 2253–2267. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msr043 Salzburger W (2018) Understanding explosive diversification through cichlid fish genomics. Nature Reviews Genetics, 19, 705–717. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-018-0043-9 Seehausen O (2004) Hybridization and adaptive radiation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 19, 198–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2004.01.003 Steenberge MV, Jublier N, Kéver L, Gresham S, Derycke S, Snoeks J, Parmentier E, Poncin P, Verheyen E (2022) The initial response of females towards congeneric males matches the propensity to hybridise in Ophthalmotilapia. bioRxiv, 2021.08.07.455508, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.07.455508 | The initial response of females towards congeneric males matches the propensity to hybridise in Ophthalmotilapia | Maarten Van Steenberge, Noemie Jublier, Loic Kever, Sophie Gresham, Sofie Derycke, Jos Snoeks, Eric Parmentier, Pascal Poncin, Erik Verheyen | <p style="text-align: justify;">Cichlid radiations often harbour closely related species with overlapping niches and distribution ranges. Such species sometimes hybridise in nature, which raises the question how can they coexist. This also holds f... |  | Aquatic, Behavior, Evolution, Fish, Vertebrates, Veterinary entomology | Ellen Decaestecker | 2021-08-09 12:22:49 | View | |

10 Mar 2022

Analyses of symbiotic bacterial communities in the plant pest Bemisia tabaci reveal high prevalence of Candidatus Hemipteriphilus asiaticus on the African continentLaurence Mouton, Helene Henri, Rahim Romba, Zainab Belgaidi, Olivier Gnankine, Fabrice Vavre https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.06.463217Cross-continents whitefly secondary symbiont revealed by metabarcodingRecommended by Yuval Gottlieb based on reviews by François Renoz, Vincent Hervé and 1 anonymous reviewerWhiteflies are serious global pests that feed on phloem sap of many agricultural crop plants. Like other phloem feeders, whiteflies rely on a primary-symbiont to supply their poor, sugar-based diet. Over time, the genomes of primary-symbionts become degraded, and they are either been replaced or complemented by co-hosted secondary-symbionts (McCutcheon and Moran 2012). In Bemisia tabaci species complex, the primary-symbiont is Candidatus Portiera aleyrodidarium, with seven secondary-symbionts that have been described to date. The prevalence and dynamics of these secondary-symbionts have been studied in various whitefly populations and genetic groups around the world, and certain combinations are determined under specific biotic and environmental factors (Zchori-Fein et al. 2014). To understand the potential metabolic or other interactions of various secondary-symbionts with Ca. Portiera aleyrodidarium and the hosts, Mouton et al. used metabarcoding approach and diagnostic PCR confirmation, to describe symbiont compositions in a collection of whiteflies from eight populations with four genetic groups in Burkina Faso. They found that one of the previously recorded secondary-symbiont from Asian whitefly populations, Candidatus Hemipteriphilus asiaticus, is also found in the tested African whiteflies. The newly identified Ca. Hemipteriphilus asiaticus forms a different strain than the ones described in Asia, and is found in high prevalence in six of the tested populations and in three genetic groups. They also showed that Portiera densities are not affected by the presence of Ca. Hemipteriphilus asiaticus. The authors suggest that based on its high prevalence, Ca. Hemipteriphilus asiaticus may benefit certain whitefly populations, however, there is no attempt to test this assumption or to relate it to environmental factors, or to identify the source of introduction. Mouton et al. bring new perspectives to the study of complex hemipteran symbioses, emphasizing the need to use both unbiased approaches such as metabarcoding, together with a priori methods such as PCR, in order to receive a complete description of symbiont population structures. Their findings are awaiting future screens for this secondary-symbiont, as well as its functional genomics and experimental manipulations to clarify its role. Discoveries on whitefly-symbionts delicate interactions are required to develop alternative control strategies for this worldly devastating pest. References McCutcheon JP, Moran NA (2012) Extreme genome reduction in symbiotic bacteria. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 10, 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2670 Mouton L, Henri H, Romba R, Belgaidi Z, Gnankiné O, Vavre F (2022) Analyses of symbiotic bacterial communities in the plant pest Bemisia tabaci reveal high prevalence of Candidatus Hemipteriphilus asiaticus on the African continent. bioRxiv, 2021.10.06.463217, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.06.463217 Zchori-Fein E, Lahav T, Freilich S (2014) Variations in the identity and complexity of endosymbiont combinations in whitefly hosts. Frontiers in Microbiology, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00310 | Analyses of symbiotic bacterial communities in the plant pest Bemisia tabaci reveal high prevalence of Candidatus Hemipteriphilus asiaticus on the African continent | Laurence Mouton, Helene Henri, Rahim Romba, Zainab Belgaidi, Olivier Gnankine, Fabrice Vavre | <p style="text-align: justify;">Microbial symbionts are widespread in insects and some of them have been associated to adaptive changes. Primary symbionts (P-symbionts) have a nutritional role that allows their hosts to feed on unbalanced diets (p... |  | Biological invasions, Pest management, Symbiosis | Yuval Gottlieb | 2021-10-11 17:45:22 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Dominique Adriaens

Ellen Decaestecker

Benoit Facon

Isabelle Schon

Emmanuel Toussaint

Bertanne Visser