Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * ▲ | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

27 Apr 2023

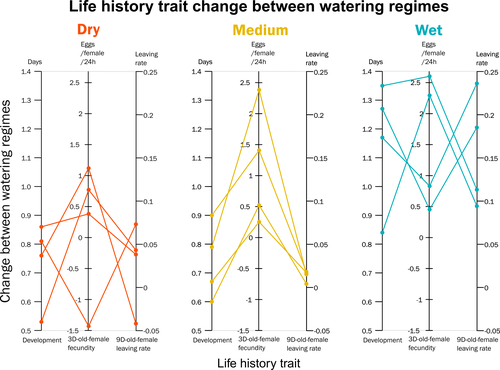

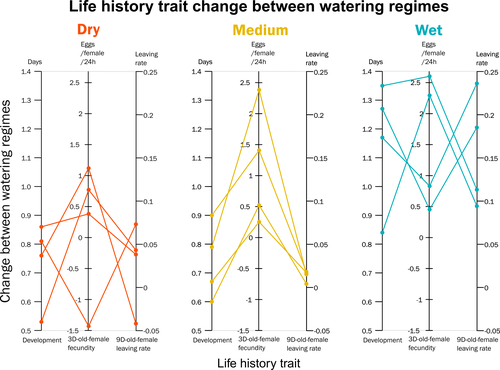

Climate of origin influences how a herbivorous mite responds to drought-stressed host plantsAlain Migeon, Philippe Auger, Odile Fossati-Gaschignard, Ruth A. Hufbauer, Maëva Miranda, Ghais Zriki, Maria Navajas https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.21.465244Not all spider-mites respond in the same way to droughtRecommended by Inês Fragata and Raul Costa-Pereira based on reviews by Bastien Castagneyrol and 2 anonymous reviewersBiotic interactions are often shaped by abiotic factors (Liu and Gaines 2022). Although this notion is not new in ecology and evolutionary biology, we are still far from a thorough understanding of how biotic interactions change along abiotic gradients in space and time. This is particularly challenging because abiotic factors can affect organisms and their interactions in multiple – direct or indirect – ways. For example, because abiotic conditions strongly determine how energy enters biological systems via producers, their effects can propagate through entire food webs, from the bottom to the top (O’Connor 2009, Gilbert et al 2019). Understanding how biological diversity - both within and across species - is shaped by the indirect effects of environmental conditions is a timely question as climate change and anthropogenic activities have been altering temperature and water availability across different ecosystems. Motivated by the current water crisis and severe droughts predicted for the near future worldwide (du Plessis 2019), Migeon et al. (2023) investigated how water limitation on producers scales up to affect life-history patterns of a widespread crop pest, the spider mite Tetranychus urticae. The authors sampled spider mite populations (n = 12) along a striking gradient of climatic conditions (>16 degrees of latitude) in Europe. After letting mites acclimate to lab conditions for several generations, the authors performed a common garden experiment to quantify how the life-history traits of mite populations from different locations respond to drought stress in their host plants. Curiously, the authors found that, when reared on drought-stressed plants, mites tended to develop faster, had higher fecundity and lower dispersion rates. This response was in line with some results obtained previously with Tetranychus species (e.g. Ximénez-Embun et al 2016). Importantly, despite some experimental caveats in the experimental design, which makes it difficult to completely disentangle the specific effects of location vs. environmental noise, results suggest the climate that populations originally experienced was also an important determinant of the plastic response in these herbivores. In fact, populations from wetter and colder regions showed a steeper change in drought response, while populations from arid climates showed a shallower response. This interesting result suggests the importance of intraspecific (between-populations) variation in the response to drought, which might be explained by the climatic heterogeneity in space throughout the evolutionary history of different populations. These results become even more important in our rapidly changing world, highlighting the importance of considering genetic variation (and conditions that generate it) when predicting plastic and evolutionary responses to stressful conditions. du Plessis, A. (2019). Current and Future Water Scarcity and Stress. In: Water as an Inescapable Risk. Springer Water. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03186-2 | Climate of origin influences how a herbivorous mite responds to drought-stressed host plants | Alain Migeon, Philippe Auger, Odile Fossati-Gaschignard, Ruth A. Hufbauer, Maëva Miranda, Ghais Zriki, Maria Navajas | <p style="text-align: justify;">Drought associated with climate change can stress plants, altering their interactions with phytophagous arthropods. Drought not only impacts cultivated plants but also their parasites, which in some cases are favore... |  | Acari, Ecology, Life histories | Inês Fragata | 2021-10-22 14:56:03 | View | |

02 Nov 2021

Cuckoo male bumblebees perform slower and longer flower visits than free-living male and worker bumblebeesAlessandro Fisogni, Gherardo Bogo, François Massol, Laura Bortolotti, Marta Galloni https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4489066Cuckoo bumblebee males might reduce plant fitnessRecommended by Michael Lattorff based on reviews by Patrick Lhomme, Silvio Erler and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Patrick Lhomme, Silvio Erler and 2 anonymous reviewers

In pollinator insects, especially bees, foraging is almost exclusively performed by females due to the close linkage with brood care. They collect pollen as a protein- and lipid-rich food to feed developing larvae in solitary and social species. Bees take carbohydrate-rich nectar in small quantities to fuel their flight and carry the pollen load. To optimise the foraging flight, they tend to be flower constant, reducing the flower handling time and time among individual inflorescences (Goulson, 1999). Males of pollinator species might be found on flowers as well. As they do not collect any pollen for brood care, their foraging flights and visits to flowers might not be shaped by the selective forces that optimise the foraging flights of females. They might stay longer in individual flowers, take up nectar if needed, but might unintentionally carry pollen on their body surface (Wolf & Moritz, 2014). | Cuckoo male bumblebees perform slower and longer flower visits than free-living male and worker bumblebees | Alessandro Fisogni, Gherardo Bogo, François Massol, Laura Bortolotti, Marta Galloni | <p>Cuckoo bumblebees are a monophyletic group within the genus Bombus and social parasites of free-living bumblebees, upon which they rely to rear their offspring. Cuckoo bumblebees lack the worker caste and visit flowers primarily for their own s... |  | Behavior, Biology, Ecology, Insecta, Invertebrates, Terrestrial | Michael Lattorff | Patrick Lhomme, Seth Barribeau , Silvio Erler, Denis Michez | 2021-02-02 01:41:35 | View |

05 Jan 2021

Do substrate roughness and gap distance impact gap-bridging strategies in arboreal chameleons?Allison M. Luger, Vincent Vermeylen, Anthony Herrel, Dominique Adriaens https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.260596Gap-bridging strategies in arboreal chameleonsRecommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Simon Baeckens and 2 anonymous reviewersUntil now, very little is known about the tail use and functional performance in tail prehensile animals. Luger et al. (2020) are the first to provide explorative observations on trait related modulation of tail use, despite the lack of a sufficiently standardized data set to allow statistical testing. They described whether gap distance, perch diameter, and perch roughness influence tail use and overall locomotor behavior of the species Chamaeleo calyptratus. References Luger, A.M., Vermeylen, V., Herrel, A. and Adriaens, D. (2020) Do substrate roughness and gap distance impact gap-bridging strategies in arboreal chameleons? bioRxiv, 2020.08.21.260596, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.260596 | Do substrate roughness and gap distance impact gap-bridging strategies in arboreal chameleons? | Allison M. Luger, Vincent Vermeylen, Anthony Herrel, Dominique Adriaens | <p>Chameleons are well-equipped for an arboreal lifestyle, having ‘zygodactylous’ hands and feet as well as a fully prehensile tail. However, to what degree tail use is preferred over autopod prehension has been largely neglected. Using an indoor ... |  | Behavior, Biology, Herpetology, Reptiles, Vertebrates | Ellen Decaestecker | 2020-08-25 10:06:42 | View | |

09 Feb 2023

A novel nematode species from the Siberian permafrost shares adaptive mechanisms for cryptobiotic survival with C. elegans dauer larvaAnastasia Shatilovich, Vamshidhar R. Gade, Martin Pippel, Tarja T. Hoffmeyer, Alexei V. Tchesunov, Lewis Stevens, Sylke Winkler, Graham M. Hughes, Sofia Traikov, Michael Hiller, Elizaveta Rivkina, Philipp H. Schiffer, Eugene W Myers, Teymuras V. Kurzchalia https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.28.478251A novel nematode species from the Siberian permafrost shares adaptive mechanisms for cryptobiotic survival with C. elegans dauer larvaRecommended by Isa Schon based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThis article [1] investigated two nematode genera, Panagrolaimus and Plectus, from the Siberian permafrost to unravel the adaptations allowing them to survive cryptobiosis; radio carbon dating showed that the individuals of Panagrolaimus had been in cryobiosis in Siberia for as long as 46,000 years! I was impressed by the multidisciplinary approach of this study, including morphological as well as phylogenetic and -genomic analyses to describe a new species. In triploids as some of the species studied here, it is quite challenging to assemble a novel genome. The authors furthermore not only managed to successfully reanimate the Siberian specimens but could also expose them to repeated freezing and desiccation in the lab, not an easy task. This study reports some amazing discoveries - comparing the molecular toolkits between C. elegans and Panagrolaimus and Plectus revealed that several components were orthologues. Likewise, some of the biochemical mechanisms for surviving freezing in the lab turned out to be similar for C. elegans and the Siberian nematodes. This study thus provides strong evidence that nematodes developed specific mechanisms allowing them to stay in cryobiosis over very long times. A surprising additional experimental result concerns the well-studied C. elegans - dauer larvae of this species can stay viable much longer after periods of animated suspension than previously thought. I highly recommend this article as it is an important contribution to the fields of evolution and molecular biology. This study greatly advanced our understanding of how nematodes could have adapted to cryobiosis. The applied techniques could also be useful for studying similar research questions in other organisms. Reference [1] Shatilovich A, Gade VR, Pippel M, Hoffmeyer TT, Tchesunov AV, Stevens L, Winkler S, Hughes GM, Traikov S, Hiller M, Rivkina E, Schiffer PH, Myers EW, Kurzchalia TV (2023) A novel nematode species from the Siberian permafrost shares adaptive mechanisms for cryptobiotic survival with C. elegans dauer larva. bioRxiv, 2022.01.28.478251, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.28.478251 | A novel nematode species from the Siberian permafrost shares adaptive mechanisms for cryptobiotic survival with C. elegans dauer larva | Anastasia Shatilovich, Vamshidhar R. Gade, Martin Pippel, Tarja T. Hoffmeyer, Alexei V. Tchesunov, Lewis Stevens, Sylke Winkler, Graham M. Hughes, Sofia Traikov, Michael Hiller, Elizaveta Rivkina, Philipp H. Schiffer, Eugene W Myers, Teymuras V. K... | <p style="text-align: justify;">Some organisms in nature have developed the ability to enter a state of suspended metabolism called cryptobiosis1 when environmental conditions are unfavorable. This state-transition requires the execution of comple... |  | Ecology, Evolution, Genetics/Genomics | Isa Schon | 2022-05-20 14:32:02 | View | |

10 Jan 2020

Culex saltanensis and Culex interfor (Diptera: Culicidae) are susceptible and competent to transmit St. Louis encephalitis virus (Flavivirus: Flaviviridae) in central ArgentinaBeranek MD, Quaglia AI, Peralta GC, Flores FS, Stein M, Diaz LA, Almirón WR and Contigiani MS https://doi.org/10.1101/722579Multiple vector species may be responsible for transmission of Saint Louis Encephalatis Virus in ArgentinaRecommended by Anna Cohuet based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersMedical and veterinary entomology is a discipline that deals with the role of insects on human and animal health. A primary objective is the identification of vectors that transmit pathogens. This is the aim of Beranek and co-authors in their study [1]. They focus on mosquito vector species responsible for transmission of St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV), an arbovirus that circulates in avian species but can incidentally occur in dead end mammal hosts such as humans, inducing symptoms and sometimes fatalities. Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus is known as the most common vector, but other species are suspected to also participate in transmission. Among them Culex saltanensis and Culex interfor have been found to be infected by the virus in the context of outbreaks. The fact that field collected mosquitoes carry virus particles is not evidence for their vector competence: indeed to be a competent vector, the mosquito must not only carry the virus, but also the virus must be able to replicate within the vector, overcome multiple barriers (until the salivary glands) and be present at sufficient titre within the saliva. This paper describes the experiments implemented to evaluate the vector competence of Cx. saltanensis and Cx. interfor from ingestion of SLEV to release within the saliva. Females emerged from field-collected eggs of Cx. pipiens quinquefasciatus, Cx. saltanensis and Cx. interfor were allowed to feed on SLEV infected chicks and viral development was measured by using (i) the infection rate (presence/absence of virus in the mosquito abdomen), (ii) the dissemination rate (presence/absence of virus in mosquito legs), and (iii) the transmission rate (presence/absence of virus in mosquito saliva). The sample size for each species is limited because of difficulties for collecting, feeding and maintaining large numbers of individuals from field populations, however the results are sufficient to show that this strain of SLEV is able to disseminate and be expelled in the saliva of mosquitoes of the three species at similar viral loads. This work therefore provides evidence that Cx saltanensis and Cx interfor are competent species for SLEV to complete its life-cycle. Vector competence does not directly correlate with the ability to transmit in real life as the actual vectorial capacity also depends on the contact between the infectious vertebrate hosts, the mosquito life expectancy and the extrinsic incubation period of the viruses. The present study does not deal with these characteristics, which remain to be investigated to complete the picture of the role of Cx saltanensis and Cx interfor in SLEV transmission. However, this study provides proof of principle that that SLEV can complete it’s life-cycle in Cx saltanensis and Cx interfor. Combined with previous knowledge on their feeding preference, this highlights their potential role as bridge vectors between birds and mammals. These results have important implications for epidemiological forecasting and disease management. Public health strategies should consider the diversity of vectors in surveillance and control of SLEV. References | Culex saltanensis and Culex interfor (Diptera: Culicidae) are susceptible and competent to transmit St. Louis encephalitis virus (Flavivirus: Flaviviridae) in central Argentina | Beranek MD, Quaglia AI, Peralta GC, Flores FS, Stein M, Diaz LA, Almirón WR and Contigiani MS | <p>Infectious diseases caused by mosquito-borne viruses constitute health and economic problems worldwide. St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV) is endemic and autochthonous in the American continent. Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus is the primary ur... |  | Medical entomology | Anna Cohuet | 2019-08-03 00:56:38 | View | |

14 Dec 2023

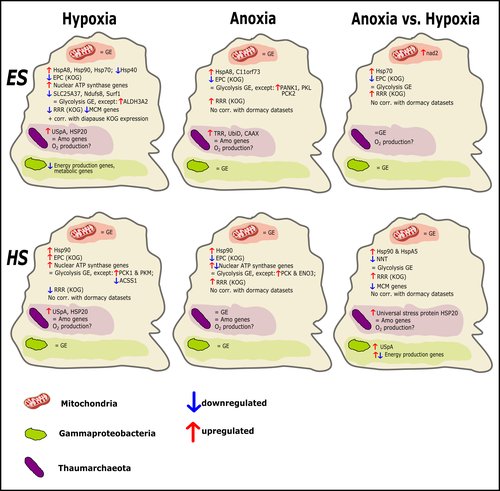

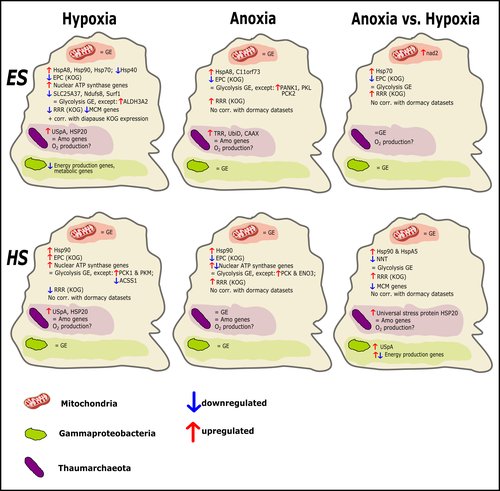

Transcriptomic responses of sponge holobionts to in situ, seasonal anoxia and hypoxiaBrian W Strehlow, Astrid Schuster, Warren R Francis, Lisa Eckford-Soper, Beate Kraft, Rob McAllen, Ronni Nielsen, Susanne Mandrup, Donald E Canfield https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.27.530229Future oceanic conditions could leave sponge holobionts breathless – but they won’t let that stop themRecommended by Loïc N. Michel based on reviews by Maria Lopez Acosta and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Maria Lopez Acosta and 2 anonymous reviewers

It is now widely accepted that anthropogenic climate change is a severe threat to biodiversity, ecosystem function and associated ecosystem services. Assessing the vulnerability of species and predicting their response to future changes has become a priority for environmental biology (Williams et al. 2020). Over the last few decades, oxygen concentrations in both the open ocean and coastal waters have been declining steadily as the result of multiple anthropogenic activities. This global trends towards hypoxia is expected to continue in the future, causing a host of negative effects on marine ecosystems. Oxygen is indeed crucial to many biological processes in the ocean, and its decrease could have strong impacts on biogeochemical cycles, and therefore on marine productivity and biodiversity (Breitburg et al. 2018). Whenever facing such drastic environmental changes, all organisms are expected to have some intrinsic ability to adapt. At shorter than evolutionary timescales, ecological plasticity and the eco-physiological processes that sustain it could constitute important adaptive mechanisms (Williams et al. 2020) Marine sponges seem particularly well-adapted to oxygen deficiency, as some species can survive seasonal anoxia for several months. This paper by Strehlow et al. (2023) examines the mechanisms allowing this exceptional tolerance. Focusing on two species of sponges, they used transcriptomics to assess how gene expression by sponges, by their mitochondria, or by their unique and species-specific microbiome could facilitate this trait. Their results suggest that sponge holobionts maintain metabolic activity under anoxic conditions while displaying shock response, therefore not supporting the hypothesis of sponge dormancy. Furthermore, hypoxia and anoxia seemed to influence gene expression in different ways, highlighting the complexity of sponge response to deoxygenation. As often, their exciting results raise as many questions as they provide answers and pave the way for more research regarding how anoxia tolerance in marine sponges could give them an advantage in future oceanic environmental conditions. References Breitburg et al. (2018): Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters. Science 359, eaam7240. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aam7240 Strehlow et al. (2023): Transcriptomic responses of sponge holobionts to in situ, seasonal anoxia and hypoxia. bioRxiv, 2023.02.27.530229, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.27.530229 Williams et al. (2008) Towards an Integrated Framework for Assessing the Vulnerability of Species to Climate Change. PLOS Biology 6(12): e325. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0060325 Williams et al. (2020): Research priorities for natural ecosystems in a changing global climate. Global Change Biology 26: 410–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14856 | Transcriptomic responses of sponge holobionts to in situ, seasonal anoxia and hypoxia | Brian W Strehlow, Astrid Schuster, Warren R Francis, Lisa Eckford-Soper, Beate Kraft, Rob McAllen, Ronni Nielsen, Susanne Mandrup, Donald E Canfield | <p>Deoxygenation can be fatal for many marine animals; however, some sponge species are tolerant of hypoxia and anoxia. Indeed, two sponge species, <em>Eurypon </em>sp. 2 and <em>Hymeraphia stellifera</em>, survive seasonal anoxia for months at a ... |  | Biology, Ecology, Genetics/Genomics, Invertebrates, Marine, Symbiosis | Loïc N. Michel | Maria Lopez Acosta | 2023-05-12 16:22:47 | View |

25 Aug 2021

Up and to the light: intra- and interspecific variability of photo- and geo-tactic oviposition preferences in genus TrichogrammaBurte, V., Perez, G., Ayed, F. , Groussier, G., Mailleret, L., van Oudenhove, L. and Calcagno, V. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.30.437671New insights into oviposition preference of 5 Trichogramma speciesRecommended by Joël Meunier based on reviews by Kévin Tougeron and Eveline C. Verhulst based on reviews by Kévin Tougeron and Eveline C. Verhulst

Insects exhibit a great diversity of life-history traits that often vary not only between species but also between populations of the same species (Flatt and Heyland, 2011). A better understanding of the variation in these traits can be of paramount importance when it comes to species of economic and agricultural interest (Wilby and Thomas, 2002). In particular, the control of the development and expansion of agricultural pests generally requires a good understanding of the parameters that favour the reproduction of these pests and/or the reproduction of the species used to control them (Bianchi et al., 2013; Gäde and Goldsworthy, 2003). Parasitoid wasps of the genus Trichogramma are a classic example of insects involved in pest control (Smith, 1996). This genus comprises over 200 species worldwide, which have been used to control populations of a wide range of lepidopteran pests since the 1900s (Flanders, 1930; Hassan, 1993). Despite its common use, the egg-laying preference of this genus is only partially known. For example, all Trichogramma species are often thought to have positive phototaxis (or negative geotaxis) (e.g. Brower & Cline, 1984; van Atta et al., 2015), but comprehensive studies simultaneously testing this (or other) parameter among Trichogramma species and populations remain rare. This is exactly the aim of the present study (Burte et al., 2021). Using a new experimental approach based on automatic image analysis, the authors compared the photo- and geo-tactic oviposition preference among 5 Trichogramma species from 25 populations. Their results first confirm that most Trichogramma species and populations prefer light to shade, and higher to lower positions for oviposition. Interestingly, they also reveal that the levels of preference for light and gravity show inter- and intraspecific variation (probably due to local adaptation to different strata) and that both preferences tend to relax over time. Overall, this study provides important information for improving the use of Trichogramma species as biological agents. For example, it may help to establish breeding lines adapted to the microhabitat and/or growing parts of plants on which agricultural pests lay eggs most. Similarly, it suggests that the use of multiple strains with different microhabitat selection preferences could lead to better coverage of host plants, as well as a reduction in intraspecific competition in the preferred parts. Finally, this study provides a new methodology to efficiently and automatically study oviposition preferences in Trichogramma, which could be used in other insects with a particularly small size. References Bianchi, F. J. J. A., Schellhorn, N. A. and Cunningham, S. A. (2013). Habitat functionality for the ecosystem service of pest control: reproduction and feeding sites of pests and natural enemies. Agricultural and Forest Entomology, 15, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-9563.2012.00586.x Burte V., Perez G., Ayed F., Groussier G., Mailleret L, van Oudenhove L. and Calcagno V. (2021). Up and to the light: intra- and interspecific variability of photo-and geo-tactic oviposition preferences in genus Trichogramma. bioRxiv, 2021.03.30.437671, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.30.437671 Brower, J. H. and Cline, L. D. (1984). Response of Trichogramma pretiosum and T. evanescens to Whitelight, Blacklight or NoLight Suction Traps. The Florida Entomologist, 67, 262–268. https://doi.org/10.2307/3493947 Flanders, S. E. (1930). Mass production of egg parasites of the genus Trichogramma. Hilgardia, 4, 465–501. https://doi.org/10.3733/hilg.v04n16p465 Flatt, T. and Heyland, A. (2011). Mechanisms of life history evolution: the genetics and physiology of life history traits and trade-offs. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199568765.001.0001 Gäde, G. and Goldsworthy, G. J. (2003). Insect peptide hormones: a selective review of their physiology and potential application for pest control. Pest Management Science, 59, 1063–1075. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.755 Hassan, S. A. (1993). The mass rearing and utilization of Trichogramma to control lepidopterous pests: Achievements and outlook. Pesticide Science, 37, 387–391. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.2780370412 Smith, S. M. (1996). Biological Control with Trichogramma : Advances, Successes, and Potential of Their Use. Annual Review of Entomology, 41, 375–406. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.41.010196.002111 van Atta, K. J., Potter, K. A. and Woods, H. A. (2015). Effects of UV-B on Environmental Preference and Egg Parasitization by Trichogramma Wasps (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae). Journal of Entomological Science, 50, 318–325. https://doi.org/10.18474/JES15-09.1 Wilby, A. and Thomas, M. B. (2002). Natural enemy diversity and pest control: patterns of pest emergence with agricultural intensification. Ecology Letters, 5, 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2002.00331.x | Up and to the light: intra- and interspecific variability of photo- and geo-tactic oviposition preferences in genus Trichogramma | Burte, V., Perez, G., Ayed, F. , Groussier, G., Mailleret, L., van Oudenhove, L. and Calcagno, V. | <p>Trichogramma are parasitic microwasps much used as biological control agents. The genus is known to harbor tremendous diversity, at both inter- and intra-specific levels. The successful selection of Trichogramma strains for biocontrol depends o... |  | Behavior, Biocontrol, Biodiversity, Ecology, Insecta, Parasitology, Pest management, Systematics, Terrestrial | Joël Meunier | Kévin Tougeron, Eveline C. Verhulst | 2021-04-02 16:10:28 | View |

21 Jun 2023

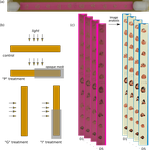

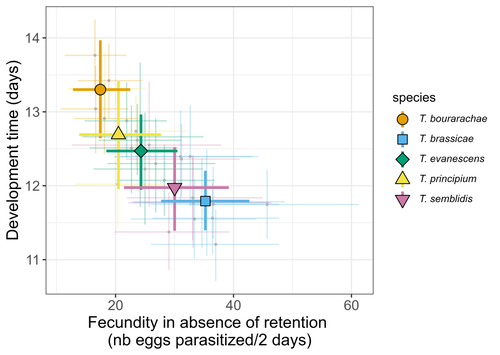

Life-history traits, pace of life and dispersal among and within five species of Trichogramma wasps: a comparative analysisChloé Guicharnaud, Géraldine Groussier, Erwan Beranger, Laurent Lamy, Elodie Vercken, Maxime Dahirel https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.24.525360The relationship between dispersal and pace-of-life at different scalesRecommended by Jacques Deere based on reviews by Mélanie Thierry and 1 anonymous reviewerThe sorting of organisms along a fast-slow continuum through correlations between life history traits is a long-standing framework (Stearns 1983) and corresponds to the pace-of-life axis. This axis represents the variation in a continuum of life-history strategies, from fast-reproducing short-lived species to slow-reproducing long-lived species. The pace-of-life axis has been the focus of much research largely in mammals, birds, reptiles and plants but less so in invertebrates (Salguero-Gómez et al. 2016; Araya-Ajoy et al. 2018; Healy et al. 2019; Bakewell et al. 2020). Outcomes from this research have highlighted variation across taxa on this axis and mixed support for, and against, patterns expected of the pace-of-life continuum. Given this, a greater understanding of the variation of the pace-of-life across-, and within, taxa are needed. Indeed, Guicharnard et al. (2023) highlight several points regarding our broader understanding of pace-of-life. In general, invertebrates are poorly represented, the variation of pace-of-life across taxonomic scales is less well understood and the relationship between pace-of-life and dispersal, a key life history, requires more attention. Here, Guicharnard et al. (2023) provide a first attempt at addressing the relationship between dispersal and pace-of-life at different scales. The authors, under controlled conditions, investigated how life-history traits and effective dispersal covary for 28 lines from five species of endoparasitoid wasps from the genus Trichogramma. At the species level negative correlations were found between development time and fecundity, matching pace-of-life axis predictions. Although this correlation was not found to be significant among lines, within species, a similar pattern of a negative correlation was observed. This outcome matches previous findings that consistent pace-of-life axes become more difficult to find at lower taxonomic levels. Unlike the other life-history traits measured, effective dispersal showed no evidence of differences between species or between lines. The authors also found no correlation between effective dispersal and other-life history traits which suggests no dispersal/life-history syndromes in the species investigated. One aspect that was not assessed was the impact of density dependence on pace-of-life and effective dispersal, largely as this was a first step in assessing relationship of dispersal with pace-of-life at different scales. However, the authors do acknowledge the importance of future studies incorporating density dependence and that such studies could potentially lead to more generalizable understanding of pace-of-life and dispersal within Trichogramma. A pleasant addition was the link to potential implications for biocontrol. This addition showed an awareness by the authors of how insights into pace-of-life can have an applied component. The results of the study highlighted that selecting for specific lines of a species, to maximise a trait of interest at the cost of another, may not be as effective as selecting different species when implementing biocontrol. This is especially important as often single, established species used in biocontrol are favoured without consideration of the potential of other species which can lead to more efficient biocontrol. REFERENCES Araya-Ajoy, Y.G., Bolstad, G.H., Brommer, J., Careau, V., Dingemanse, N.J. & Wright, J. (2018). Demographic measures of an individual's "pace of life": fecundity rate, lifespan, generation time, or a composite variable? Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 72, 75. | Life-history traits, pace of life and dispersal among and within five species of *Trichogramma* wasps: a comparative analysis | Chloé Guicharnaud, Géraldine Groussier, Erwan Beranger, Laurent Lamy, Elodie Vercken, Maxime Dahirel | <p>Major traits defining the life history of organisms are often not independent from each other, with most of their variation aligning along key axes such as the pace-of-life axis. We can define a pace-of-life axis structuring reproduction and de... |  | Biology, Ecology, Insecta, Invertebrates, Life histories | Jacques Deere | 2023-01-25 18:15:20 | View | |

22 Jul 2020

The open bar is closed: restructuration of a native parasitoid community following successful control of an invasive pest.David Muru, Nicolas Borowiec, Marcel Thaon, Nicolas Ris, Madalina Ionela Viciriuc, Sylvie Warot, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.20.884908Raise and fall of an invasive pest and consequences for native parasitoid communitiesRecommended by Stefaniya Kamenova based on reviews by Kévin Tougeron and Miguel González Ximénez de EmbúnHost-parasitoid interactions have been the focus of extensive ecological research for decades. One the of the major reasons is the importance host-parasitoid interactions play for the biological control of crop pests. Parasitoids are the main natural regulators for a large number of economically important pest insects, and in many cases they could be the only viable crop protection strategy. Parasitoids are also integral part of complex food webs whose structure and diversity display large spatio-temporal variations [1-3]. With the increasing globalization of human activities, the generalized spread and establishment of invasive species is a major cause of disruption in local community and food web spatio-temporal dynamics. In particular, the deliberate introduction of non-native parasitoids as part of biological control programs, aiming the suppression of established, and also highly invasive crop pests, is a common practice with potentially significant, yet poorly understood effects on local food web dynamics (e.g. [4]). References [1] Eveleigh ES, McCann KS, McCarthy PC, Pollock SJ, Lucarotti CJ, Morin B, McDougall GA, Strongman DB, Huber JT, Umbanhowar J, Faria LDB (2007). Fluctuations in density of an outbreak species drive diversity cascades in food webs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 16976-16981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704301104 | The open bar is closed: restructuration of a native parasitoid community following successful control of an invasive pest. | David Muru, Nicolas Borowiec, Marcel Thaon, Nicolas Ris, Madalina Ionela Viciriuc, Sylvie Warot, Elodie Vercken | <p>The rise of the Asian chestnut gall wasp *Dryocosmus kuriphilus* in France has benefited the native community of parasitoids originally associated with oak gall wasps by becoming an additional trophic subsidy and therefore perturbing population... |  | Biocontrol, Biological invasions, Ecology, Insecta | Stefaniya Kamenova | 2019-12-31 09:08:49 | View | |

25 Aug 2022

Improving species conservation plans under IUCN's One Plan Approach using quantitative genetic methodsDrew Sauve, Jane Hudecki, Jessica Steiner, Hazel Wheeler, Colleen Lynch, Amy A. Chabot https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/n3zxpQuantitative genetics for a more qualitative conservationRecommended by Peter Galbusera based on reviews by Timothée Bonnet and 1 anonymous reviewerGenetic (bio)diversity is one of three recognised levels of biodiversity, besides species and ecosystem diversity. Its importance for species survival and adaptation is increasingly highlighted and its monitoring recommended (e.g. O’Brien et al 2022). Especially the management of ex-situ populations has a long history of taking into account genetic aspects (through pedigree analysis but increasingly also by applying molecular tools). As in-situ and ex-situ efforts are nowadays often aligned (in a One-Plan-Approach), genetic management is becoming more the standard (supported by quickly developing genomic techniques). However, rarely quantitative genetic aspects are raised in this issue, while its relevance cannot be underestimated. Hence, the current manuscript by Sauve et al (2022) is a welcome contribution, in order to improve conservation efforts. The authors give a clear overview on how quantitative genetic analysis can aid the measurement, monitoring, prediction and management of adaptive genetic variation. The main tools are pedigrees (mainly of ex-situ populations) and the Animal Model. The main goal is to prevent adaption to captivity and altered genetics in general (in reintroduction projects). The confounding factors to take into account (like inbreeding, population structure, differences between facilities, sample size and parental/social effects) are well described by the authors. As such, I fully recommend this manuscript for publication, hoping increased interest in quantitative analysis will benefit the quality of species conservation management. References O'Brien D, Laikre L, Hoban S, Bruford MW et al. (2022) Bringing together approaches to reporting on within species genetic diversity. Journal of Applied Ecology, 00, 1–7. https://doi/10.1111/1365-2664.14225 Sauve D., Spero J., Steiner J., Wheeler H., Lynch C., Chabot A.A. (2022) Improving species conservation plans under IUCN’s One Plan Approach using quantitative genetic methods. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 9 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/n3zxp | Improving species conservation plans under IUCN's One Plan Approach using quantitative genetic methods | Drew Sauve, Jane Hudecki, Jessica Steiner, Hazel Wheeler, Colleen Lynch, Amy A. Chabot | <p>Human activities are resulting in altered environmental conditions that are impacting the demography and evolution of species globally. If we wish to prevent anthropogenic extinction and extirpation, we need to improve our ability to restore wi... |  | Conservation biology, Ecology, Evolution, Genetics/Genomics | Peter Galbusera | 2022-02-21 10:45:22 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Dominique Adriaens

Ellen Decaestecker

Benoit Facon

Isabelle Schon

Emmanuel Toussaint

Bertanne Visser