LATTORFF Michael

- School of Life Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

- Behavior, Biodiversity, Biology, Ecology, Ecosystems, Evolution, Genetics/Genomics, Insecta, Life histories, Molecular biology, Parasitology, Physiology, Terrestrial

- recommender

Recommendations: 4

Reviews: 0

Recommendations: 4

Brood thermoregulation effectivenessis positively linked to the amount of brood but not to the number of bees in honeybee colonies

Precision and accuracy of honeybee thermoregulation

Recommended by Michael Lattorff based on reviews by Jakob Wegener and Christopher MayackThe Western honeybee, Apis mellifera L., is one of the best-studied social insects. It shows a reproductive division of labour, cooperative brood care, and age-related polyethism. Furthermore, honeybees regulate the temperature in the hive. Although bees are invertebrates that are usually ectothermic, this is still true for individual worker bees, but the colony maintains a very narrow range of temperature, especially within the brood nest. This is quite important as the development of individuals is dependent on ambient temperature, with higher temperatures resulting in accelerated development and vice versa. In honeybees, a feedback mechanism couples developmental temperature and the foraging behaviour of the colony and the future population development (Tautz et al., 2003). Bees raised under lower temperatures are more likely to perform in-hive tasks, while bees raised under higher temperatures are better foragers. To maintain optimal levels of worker population growth and foraging rates, it is adaptive to regulate temperature to ensure optimal levels of developing brood. Moreover, this allows honeybees to decouple the internal developmental processes from ambient temperatures enhancing the ecological success of the species.

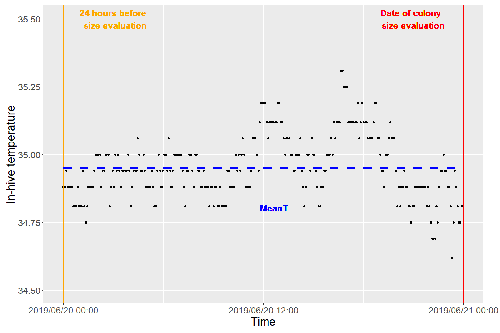

In every system of thermoregulation, whether it is endothermic under the utilization of energetic resources as in mammals or the honeybee or ectothermic as in lower vertebrates and invertebrates through differential exposure to varying environmental temperature gradients, there is a need for precision (low variability) and accuracy (hitting the target temperature). However, in honeybees, the temperature is regulated by workers through muscle contraction and fanning of the wings and thus, a higher number of workers could be better at achieving precise and accurate temperature within the brood nest. Alternatively, the amount of brood could trigger responses with more brood available, a need for more precise and accurate temperature control. The authors aimed at testing these two important factors on the precision and accuracy of within-colony temperature regulation by monitoring 28 colonies equipped with temperature sensors for two years (Godeau et al., 2023).

They found that the number of brood cells predicted the mean temperature (accuracy of thermoregulation). Other environmental factors had a small effect. However, the model incorporating these factors was weak in predicting the temperature as it overestimated temperatures in lower ranges and underestimated temperatures in higher ranges. In contrast, the variability of the target temperature (precision of thermoregulation) was positively affected by the external temperature, while all other factors did not show a significant effect. Again, the model was weak in predicting the data. Overall colony size measured in categories of the number of workers and the number of brood cells did not show major differences in variability of the mean temperature, but a slight positive effect for the number of bees on the mean temperature.

Unfortunately, the temperature was a poor predictor of colony size. The latter is important as the remote control of beehives using Internet of Things (IoT) technologies get more and more incorporated into beekeeping management. These IoT technologies and their success are dependent on good proxies for the control of the status of the colony. Amongst the factors to monitor, the colony size (number of bees and/or amount of brood) is extremely important, but temperature measurements alone will not allow us to predict colony sizes. Nevertheless, this study showed clearly that the number of brood cells is a crucial factor for the accuracy of thermoregulation in the beehive, while ambient temperature affects the precision of thermoregulation. In the view of climate change, the latter factor seems to be important, as more extreme environmental conditions in the future call for measures of mitigation to ensure the proper functioning of the bee colony, including the maintenance of homeostatic conditions inside of the nest to ensure the delivery of the ecosystem service of pollination.

REFERENCES

Godeau U, Pioz M, Martin O, Rüger C, Crauser D, Le Conte Y, Henry M, Alaux C (2023) Brood thermoregulation effectiveness is positively linked to the amount of brood but not to the number of bees in honeybee colonies. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/9mwye

Tautz J, Maier S, Claudia Groh C, Wolfgang Rössler W, Brockmann A (2003) Behavioral performance in adult honey bees is influenced by the temperature experienced during their pupal development. PNAS 100: 7343–7347. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1232346100

Population genetics of Glossina fuscipes fuscipes from southern Chad

Population genetics of tsetse, the vector of African Trypanosomiasis, helps informing strategies for control programs

Recommended by Michael Lattorff based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersHuman African Trypanosomiasis (HAT), or sleeping sickness, is caused by trypanosome parasites. In sub-Saharan Africa, two forms are present, Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and T. b. rhodesiense, the former responsible for 95% of reported cases. The parasites are transmitted through a vector, Genus Glossina, also known as tsetse, which means fly in Tswana, a language from southern Africa. Through a blood meal, tsetse picks up the parasite from infected humans or animals (in animals, the parasite causes Animal African Trypanosomiasis or nagana disease). Through medical interventions and vector control programs, the burden of the disease has drastically reduced over the past two decades, so the WHO neglected tropical diseases road map targets the interruption of transmission (zero cases) for 2030 (WHO 2022).

Meaningful vector control programs utilize traps for the removal of animals and for surveillance, along with different methods of spraying insecticides. However, in existing HAT risk areas, it will be essential to understand the ecology of the vector species to implement control programs in a way that areas cleared from the vector will not be reinvaded from other populations. Thus, it will be crucial to understand basic population genetics parameters related to population structure and subdivision, migration frequency and distances, population sizes, and the potential for sex-biased dispersal. The authors utilize genotyping using nine highly polymorphic microsatellite markers of samples from Chad collected in differently affected regions and at different time points (Ravel et al., 2023). Two major HAT zones exist that are targeted by vector control programs, namely Madoul and Maro, while two other areas, Timbéri and Dokoutou, are free of trypanosomes. Samples were taken before vector control programs started.

The sex ratio was female-biased, most strongly in Mandoul and Maro, the zones with the lowest population density. This could be explained by resource limitation, which could be the hosts for a blood meal or the sites for larviposition. Limited resources mean that females must fly further, increasing the chance that more females are caught in traps.

The effective population densities of Mandoul and Maro were low. However, there was a convergence of population density and trapping density, which might be explained by the higher preservation of flies in the high-density areas of Timbéri and Dokoutou after the first round of sampling, which can only be tested using a second sampling.

The dispersal distances are the highest recorded so far, especially in Mandoul and Maro, with 20-30 km per generation. However, in Timbéri and Dokoutou, which are 50 km apart, very little exchange occurs (approx. 1-2 individuals every six months). A major contributor to this is the massive destruction of habitat that started in the early 1990s and left patchily distributed and fragmented habitats. The Mandoul zone might be safe from reinvasion after eradication, as for a successful re-establishment, either a pair of a female and male or a pregnant female are required. As the trypanosome prevalence amongst humans was 0.02 and of tsetse 0.06 (Ibrahim et al., 2021) before interventions began, medical interventions and vector control might have further reduced these levels, making a reinvasion and subsequent re-establishment of HAT very unlikely. Maro is close to the border of the Central African Republic, and the area has not been well investigated concerning refugee populations of tsetse, which could contribute to a reinvasion of the Maro zone. The higher level of genetic heterogeneity of the Maro population indicates that invasions from neighboring populations are already ongoing. This immigration could also be the reason for not detecting the bottleneck signature in the Maro population.

The two HAT areas need different levels of attention while implementing vector eradication programs. While Madoul is relatively safe against reinvasion, Maro needs another type of attention, as frequent and persistent immigration might counteract eradication efforts. Thus, it is recommended that continuous tsetse suppression needs to be implemented in Maro.

This study shows nicely that an in-depth knowledge of the processes within and between populations is needed to understand how these populations behave. This can be used to extrapolate, make predictions, and inform the organisations implementing vector control programs to include valuable adjustments, as in the case of Maro. Such integrative approaches can help prevent the failure of programs, potentially saving costs and preventing infections of humans and animals who might die if not treated.

References

Ibrahim MAM, Weber JS, Ngomtcho SCH, Signaboubo D, Berger P, Hassane HM, Kelm S (2021) Diversity of trypanosomes in humans and cattle in the HAT foci Mandoul and Maro, Southern Chad- Southern Chad-A matter of concern for zoonotic potential? PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 15, e000 323. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0009323

Ravel S, Mahamat MH, Ségard A, Argiles-Herrero R, Bouyer J, Rayaisse JB, Solano P, Mollo BG, Pèka M, Darnas J, Belem AMG, Yoni W, Noûs C, de Meeûs T (2023) Population genetics of Glossina fuscipes fuscipes from southern Chad. Zenodo, ver. 9 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7763870

WHO (2022) Trypanosomiasis, human African (sleeping sickness). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/trypanosomiasis-human-african-(sleeping-sickness), retrieved 17. March 2023

A simple procedure to detect, test for the presence of stuttering, and cure stuttered data with spreadsheet programs

Improved population genetics parameters through control for microsatellite stuttering

Recommended by Michael Lattorff based on reviews by Thibaut Malausa, Fabien Halkett and Thierry RigaudMolecular markers have drastically changed and improved our understanding of biological processes. In combination with PCR, markers revolutionized the study of all organisms, even tiny insects, and eukaryotic pathogens amongst others. Microsatellite markers were the most prominent and successful ones. Their success started in the early 1990s. They were used for population genetic studies, mapping of genes and genomes, and paternity testing and inference of relatedness. Their popularity is based on some of their characteristics as codominance, the high polymorphism information content, and their ease of isolation (Schlötterer 2004). Still, microsatellites are the marker of choice for a range of non-model organisms as next-generation sequencing technologies produce a huge amount of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), but often at expense of sample size and higher costs.

The high level of polymorphism of microsatellite markers, which consist of one to six base-pair nucleotide motifs replicated up to 10 or 20 times, results from slippage events during DNA replication. Short hairpin loops might shorten the template strand or extend the new strand. However, such slippage events might occur during PCR amplification resulting in additional bands or peaks. Such stutter alleles often appear to differ by one repeat unit and might be hard to interpret but definitively reduce automated scoring of microsatellite results.

A standalone software package available to handle stuttering is Microchecker (van Oosterhout et al., 2004, which nowadays faces incompatibilities with updated versions of different operating systems. Thus, de Meeûs and Noûs (2022), in their manuscript, tackled the stuttering issue by developing an OS-independent analysis pipeline based on standard spreadsheet software such as Microsoft Office (Excel) or Apache Open Office (Calc). The authors use simulated populations differing in the mating system (pangamic, selfing (30%), clonal) and a different number of subpopulations and individuals per subpopulation to test for differences among the null model (no stuttering), a test population with 2 out of 20 loci (10%) with stuttering, and the latter with stuttering cured. Further to this, the authors also re-analyse data from previous studies utilising organisms differing in the mating system to understand whether control of stuttering changes major parameter estimates and conclusions of those studies.

Stuttering of microsatellite loci might result in increased heterozygote deficits. The authors utilise the FIS (inbreeding coefficient) as a tool to compare the different treatments of the simulated populations. Their method detected stuttering in pangamic and selfing populations, while the detection of stuttering in clonal organisms is more difficult. The cure for stuttering resulted in FIS values similar to those populations lacking stuttering. The re-analysis of four previously published studies indicated that the new method presented here is more accurate than Microchecker (van Oosterhout et al., 2004) in a direct comparison. For the Lyme disease-transmitting tick Ixodes scapularis (De Meeûs et al., 2021), three loci showed stuttering and curing these resulted in data that are in good agreement with pangamic reproduction. In the tsetse fly Glossina palpalis palpalis (Berté et al., 2019), two out of seven loci were detected as stuttering. Curing them resulted in decreased FIS for one locus, while the other showed an increased FIS, an indication of other problems such as the occurrence of null alleles. Overall, in dioecious pangamic populations, the method works well, and the cure of stuttering improves population genetic parameter estimates, although FST and FIS might be slightly overestimated. In monoecious selfers, the detection and cure work well, if other factors such as null alleles do not interfere. In clonal organisms, only loci with extremely high FIS might need a cure to improve parameter estimates.

This spreadsheet-based method helps to automate microsatellite analysis at very low costs and thus improves the accuracy of parameter estimates. This might certainly be very useful for a range of non-model organisms, parasites, and their vectors, for which microsatellites are still the marker of choice.

References

Berté D, De Meeus T, Kaba D, Séré M, Djohan V, Courtin F, N'Djetchi KM, Koffi M, Jamonneau V, Ta BTD, Solano P, N’Goran EK, Ravel S (2019) Population genetics of Glossina palpalis palpalis in sleeping sickness foci of Côte d'Ivoire before and after vector control. Infection Genetics and Evolution 75, 103963. https://doi.org/0.1016/j.meegid.2019.103963

de Meeûs T, Chan CT, Ludwig JM, Tsao JI, Patel J, Bhagatwala J, Beati L (2021) Deceptive combined effects of short allele dominance and stuttering: an example with Ixodes scapularis, the main vector of Lyme disease in the U.S.A. Peer Community Journal 1, e40. https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.34

de Meeûs T, Noûs C (2022) A simple procedure to detect, test for the presence of stuttering, and cure stuttered data with spreadsheet programs. Zenodo, v5, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7029324

Schlötterer C (2004) The evolution of molecular markers - just a matter of fashion? Nature Reviews Genetics 5, 63-69. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg1249

van Oosterhout C, Hutchinson WF, Wills DPM, Shipley P (2004) MICRO-CHECKER: software for identifying and correcting genotyping errors in microsatellite data. Molecular Ecology Notes 4, 535-538. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-8286.2004.00684.x

Cuckoo male bumblebees perform slower and longer flower visits than free-living male and worker bumblebees

Cuckoo bumblebee males might reduce plant fitness

Recommended by Michael Lattorff based on reviews by Patrick Lhomme, Silvio Erler and 2 anonymous reviewersIn pollinator insects, especially bees, foraging is almost exclusively performed by females due to the close linkage with brood care. They collect pollen as a protein- and lipid-rich food to feed developing larvae in solitary and social species. Bees take carbohydrate-rich nectar in small quantities to fuel their flight and carry the pollen load. To optimise the foraging flight, they tend to be flower constant, reducing the flower handling time and time among individual inflorescences (Goulson, 1999). Males of pollinator species might be found on flowers as well. As they do not collect any pollen for brood care, their foraging flights and visits to flowers might not be shaped by the selective forces that optimise the foraging flights of females. They might stay longer in individual flowers, take up nectar if needed, but might unintentionally carry pollen on their body surface (Wolf & Moritz, 2014).

Bumblebees are excellent pollinators (Goulson, 2010), and a few species are exploited commercially for their delivery of pollination services (Velthuis & van Doorn, 2006). However, a monophyletic group of socially parasitic species – cuckoo bumblebees – has evolved amongst the bumblebees, lacking a worker caste. Cuckoo bee gynes usurp nests of free-living bumblebees, kill the resident queen, and forces the host workers to rear their offspring consisting of gynes and males (Lhomme & Hines, 2019). The level of affected colonies in an area can be up to 42% (Erler & Lattorff, 2010).

The behaviour of the cuckoo bumblebees, especially that of the males, has been rarely studied. The present study by Fisogni et al. (2021) has targeted the flower-visiting behaviour of workers and males of free-living bumblebees and males of the cuckoo species. They used behavioural observations of flower-visiting insects on Gentiana lutea, a plant from south-eastern Europe with yellow flowers arranged in whorls. While all three groups of bees visited the same number of plants, males of both types visited more flowers within a whorl, but cuckoo males spent more time on flowers within a whorl and the whole plant than the free-living bumblebees.

The flower visits of bumblebee workers are optimised, aiming at collecting as much pollen as possible within a short time frame. This, in turn, has consequences for the pollination process by enhancing cross-pollination between different plants. By contrast, males and especially cuckoo bumblebee males, are not selected for an optimised foraging pattern. Instead, they spend more time on flowers, eventually resulting in higher levels of pollen transfer within a plant (geitonogamy), which might lead to reduced plant fitness. This is the first study to relate the foraging behaviour of cuckoo bumblebees to pollination and plant fitness.

References

Erler, S., & Lattorff, H. M. G. (2010). The degree of parasitism of the bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) by cuckoo bumblebees (Bombus (Psithyrus) vestalis). Insectes sociaux, 57(4), 371-377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-010-0093-2

Fisogni, A., Bogo, G., Massol, F., Bortolotti, L., Galloni, M. (2021). Cuckoo male bumblebees perform slower and longer flower visits than free-living male and worker bumblebees. Zenodo, 10.5281/zenodo.4489066, ver. 1.2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4489066

Goulson, D. (1999). Foraging strategies of insects for gathering nectar and pollen, and implications for plant ecology and evolution. Perspectives in plant ecology, evolution and systematics, 2(2), 185-209. https://doi.org/10.1078/1433-8319-00070

Goulson, D. (2010). Bumblebees. Behaviour, Ecology, and Conservation, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Lhomme, P., Hines, H. M. (2019). Ecology and evolution of cuckoo bumble bees. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 112, 122-140. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/say031

Velthuis, H. H. W., van Doorn, A. (2006). A century of advances in bumblebee domestication and the economic and environmental aspects of its commercialization for pollination. Apidologie, 37, 421-451. https://doi.org/10.1051/apido:2006019

Wolf, S., Moritz, R. F. A. (2014). The pollination potential of free-foraging bumblebee (Bombus spp.) males (Hymenoptera. Apidae). Apidologie, 45, 440-450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-013-0259-9