Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers▼ | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

02 Nov 2021

Cuckoo male bumblebees perform slower and longer flower visits than free-living male and worker bumblebeesAlessandro Fisogni, Gherardo Bogo, François Massol, Laura Bortolotti, Marta Galloni https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4489066Cuckoo bumblebee males might reduce plant fitnessRecommended by Michael Lattorff based on reviews by Patrick Lhomme, Silvio Erler and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Patrick Lhomme, Silvio Erler and 2 anonymous reviewers

In pollinator insects, especially bees, foraging is almost exclusively performed by females due to the close linkage with brood care. They collect pollen as a protein- and lipid-rich food to feed developing larvae in solitary and social species. Bees take carbohydrate-rich nectar in small quantities to fuel their flight and carry the pollen load. To optimise the foraging flight, they tend to be flower constant, reducing the flower handling time and time among individual inflorescences (Goulson, 1999). Males of pollinator species might be found on flowers as well. As they do not collect any pollen for brood care, their foraging flights and visits to flowers might not be shaped by the selective forces that optimise the foraging flights of females. They might stay longer in individual flowers, take up nectar if needed, but might unintentionally carry pollen on their body surface (Wolf & Moritz, 2014). | Cuckoo male bumblebees perform slower and longer flower visits than free-living male and worker bumblebees | Alessandro Fisogni, Gherardo Bogo, François Massol, Laura Bortolotti, Marta Galloni | <p>Cuckoo bumblebees are a monophyletic group within the genus Bombus and social parasites of free-living bumblebees, upon which they rely to rear their offspring. Cuckoo bumblebees lack the worker caste and visit flowers primarily for their own s... |  | Behavior, Biology, Ecology, Insecta, Invertebrates, Terrestrial | Michael Lattorff | Patrick Lhomme, Seth Barribeau , Silvio Erler, Denis Michez | 2021-02-02 01:41:35 | View |

27 Apr 2023

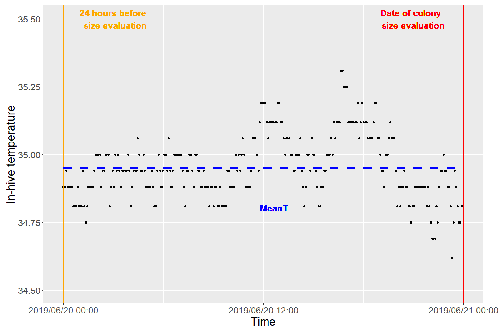

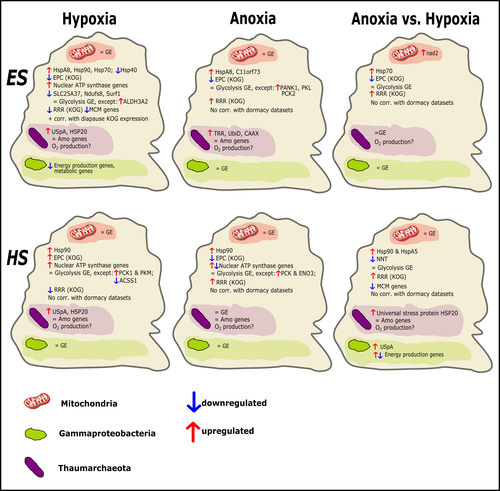

Brood thermoregulation effectivenessis positively linked to the amount of brood but not to the number of bees in honeybee coloniesUgoline Godeau, Maryline Pioz, Olivier Martin, Charlotte Rüger, Didier Crauser, Yves Le Conte, Mickael Henry, Cédric Alaux https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/9mwyePrecision and accuracy of honeybee thermoregulationRecommended by Michael Lattorff based on reviews by Jakob Wegener and Christopher Mayack based on reviews by Jakob Wegener and Christopher Mayack

The Western honeybee, Apis mellifera L., is one of the best-studied social insects. It shows a reproductive division of labour, cooperative brood care, and age-related polyethism. Furthermore, honeybees regulate the temperature in the hive. Although bees are invertebrates that are usually ectothermic, this is still true for individual worker bees, but the colony maintains a very narrow range of temperature, especially within the brood nest. This is quite important as the development of individuals is dependent on ambient temperature, with higher temperatures resulting in accelerated development and vice versa. In honeybees, a feedback mechanism couples developmental temperature and the foraging behaviour of the colony and the future population development (Tautz et al., 2003). Bees raised under lower temperatures are more likely to perform in-hive tasks, while bees raised under higher temperatures are better foragers. To maintain optimal levels of worker population growth and foraging rates, it is adaptive to regulate temperature to ensure optimal levels of developing brood. Moreover, this allows honeybees to decouple the internal developmental processes from ambient temperatures enhancing the ecological success of the species. In every system of thermoregulation, whether it is endothermic under the utilization of energetic resources as in mammals or the honeybee or ectothermic as in lower vertebrates and invertebrates through differential exposure to varying environmental temperature gradients, there is a need for precision (low variability) and accuracy (hitting the target temperature). However, in honeybees, the temperature is regulated by workers through muscle contraction and fanning of the wings and thus, a higher number of workers could be better at achieving precise and accurate temperature within the brood nest. Alternatively, the amount of brood could trigger responses with more brood available, a need for more precise and accurate temperature control. The authors aimed at testing these two important factors on the precision and accuracy of within-colony temperature regulation by monitoring 28 colonies equipped with temperature sensors for two years (Godeau et al., 2023). They found that the number of brood cells predicted the mean temperature (accuracy of thermoregulation). Other environmental factors had a small effect. However, the model incorporating these factors was weak in predicting the temperature as it overestimated temperatures in lower ranges and underestimated temperatures in higher ranges. In contrast, the variability of the target temperature (precision of thermoregulation) was positively affected by the external temperature, while all other factors did not show a significant effect. Again, the model was weak in predicting the data. Overall colony size measured in categories of the number of workers and the number of brood cells did not show major differences in variability of the mean temperature, but a slight positive effect for the number of bees on the mean temperature. Unfortunately, the temperature was a poor predictor of colony size. The latter is important as the remote control of beehives using Internet of Things (IoT) technologies get more and more incorporated into beekeeping management. These IoT technologies and their success are dependent on good proxies for the control of the status of the colony. Amongst the factors to monitor, the colony size (number of bees and/or amount of brood) is extremely important, but temperature measurements alone will not allow us to predict colony sizes. Nevertheless, this study showed clearly that the number of brood cells is a crucial factor for the accuracy of thermoregulation in the beehive, while ambient temperature affects the precision of thermoregulation. In the view of climate change, the latter factor seems to be important, as more extreme environmental conditions in the future call for measures of mitigation to ensure the proper functioning of the bee colony, including the maintenance of homeostatic conditions inside of the nest to ensure the delivery of the ecosystem service of pollination. REFERENCES Godeau U, Pioz M, Martin O, Rüger C, Crauser D, Le Conte Y, Henry M, Alaux C (2023) Brood thermoregulation effectiveness is positively linked to the amount of brood but not to the number of bees in honeybee colonies. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/9mwye Tautz J, Maier S, Claudia Groh C, Wolfgang Rössler W, Brockmann A (2003) Behavioral performance in adult honey bees is influenced by the temperature experienced during their pupal development. PNAS 100: 7343–7347. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1232346100 | Brood thermoregulation effectivenessis positively linked to the amount of brood but not to the number of bees in honeybee colonies | Ugoline Godeau, Maryline Pioz, Olivier Martin, Charlotte Rüger, Didier Crauser, Yves Le Conte, Mickael Henry, Cédric Alaux | <p style="text-align: justify;">To ensure the optimal development of brood, a honeybee colony needs to regulate its temperature within a certain range of values (thermoregulation), regardless of environmental changes in biotic and abiotic factors.... |  | Biology, Conservation biology, Demography/population dynamics, Ecology, Insecta | Michael Lattorff | Mauricio Daniel Beranek | 2022-07-06 09:20:10 | View |

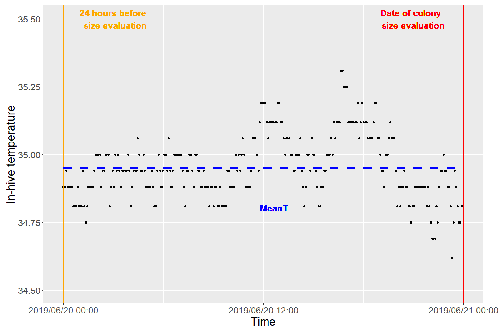

14 Dec 2023

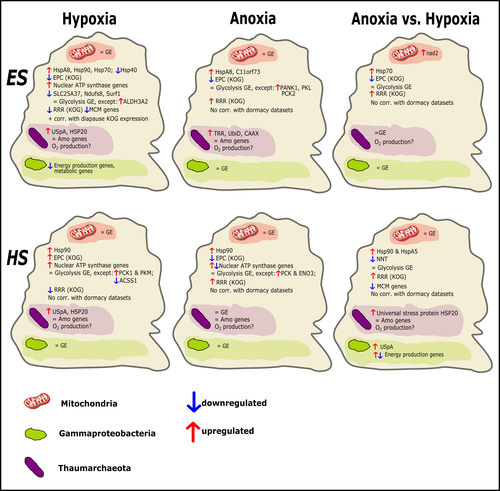

Transcriptomic responses of sponge holobionts to in situ, seasonal anoxia and hypoxiaBrian W Strehlow, Astrid Schuster, Warren R Francis, Lisa Eckford-Soper, Beate Kraft, Rob McAllen, Ronni Nielsen, Susanne Mandrup, Donald E Canfield https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.27.530229Future oceanic conditions could leave sponge holobionts breathless – but they won’t let that stop themRecommended by Loïc N. Michel based on reviews by Maria Lopez Acosta and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Maria Lopez Acosta and 2 anonymous reviewers

It is now widely accepted that anthropogenic climate change is a severe threat to biodiversity, ecosystem function and associated ecosystem services. Assessing the vulnerability of species and predicting their response to future changes has become a priority for environmental biology (Williams et al. 2020). Over the last few decades, oxygen concentrations in both the open ocean and coastal waters have been declining steadily as the result of multiple anthropogenic activities. This global trends towards hypoxia is expected to continue in the future, causing a host of negative effects on marine ecosystems. Oxygen is indeed crucial to many biological processes in the ocean, and its decrease could have strong impacts on biogeochemical cycles, and therefore on marine productivity and biodiversity (Breitburg et al. 2018). Whenever facing such drastic environmental changes, all organisms are expected to have some intrinsic ability to adapt. At shorter than evolutionary timescales, ecological plasticity and the eco-physiological processes that sustain it could constitute important adaptive mechanisms (Williams et al. 2020) Marine sponges seem particularly well-adapted to oxygen deficiency, as some species can survive seasonal anoxia for several months. This paper by Strehlow et al. (2023) examines the mechanisms allowing this exceptional tolerance. Focusing on two species of sponges, they used transcriptomics to assess how gene expression by sponges, by their mitochondria, or by their unique and species-specific microbiome could facilitate this trait. Their results suggest that sponge holobionts maintain metabolic activity under anoxic conditions while displaying shock response, therefore not supporting the hypothesis of sponge dormancy. Furthermore, hypoxia and anoxia seemed to influence gene expression in different ways, highlighting the complexity of sponge response to deoxygenation. As often, their exciting results raise as many questions as they provide answers and pave the way for more research regarding how anoxia tolerance in marine sponges could give them an advantage in future oceanic environmental conditions. References Breitburg et al. (2018): Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters. Science 359, eaam7240. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aam7240 Strehlow et al. (2023): Transcriptomic responses of sponge holobionts to in situ, seasonal anoxia and hypoxia. bioRxiv, 2023.02.27.530229, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.27.530229 Williams et al. (2008) Towards an Integrated Framework for Assessing the Vulnerability of Species to Climate Change. PLOS Biology 6(12): e325. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0060325 Williams et al. (2020): Research priorities for natural ecosystems in a changing global climate. Global Change Biology 26: 410–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14856 | Transcriptomic responses of sponge holobionts to in situ, seasonal anoxia and hypoxia | Brian W Strehlow, Astrid Schuster, Warren R Francis, Lisa Eckford-Soper, Beate Kraft, Rob McAllen, Ronni Nielsen, Susanne Mandrup, Donald E Canfield | <p>Deoxygenation can be fatal for many marine animals; however, some sponge species are tolerant of hypoxia and anoxia. Indeed, two sponge species, <em>Eurypon </em>sp. 2 and <em>Hymeraphia stellifera</em>, survive seasonal anoxia for months at a ... |  | Biology, Ecology, Genetics/Genomics, Invertebrates, Marine, Symbiosis | Loïc N. Michel | Maria Lopez Acosta | 2023-05-12 16:22:47 | View |

25 Aug 2021

Up and to the light: intra- and interspecific variability of photo- and geo-tactic oviposition preferences in genus TrichogrammaBurte, V., Perez, G., Ayed, F. , Groussier, G., Mailleret, L., van Oudenhove, L. and Calcagno, V. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.30.437671New insights into oviposition preference of 5 Trichogramma speciesRecommended by Joël Meunier based on reviews by Kévin Tougeron and Eveline C. Verhulst based on reviews by Kévin Tougeron and Eveline C. Verhulst

Insects exhibit a great diversity of life-history traits that often vary not only between species but also between populations of the same species (Flatt and Heyland, 2011). A better understanding of the variation in these traits can be of paramount importance when it comes to species of economic and agricultural interest (Wilby and Thomas, 2002). In particular, the control of the development and expansion of agricultural pests generally requires a good understanding of the parameters that favour the reproduction of these pests and/or the reproduction of the species used to control them (Bianchi et al., 2013; Gäde and Goldsworthy, 2003). Parasitoid wasps of the genus Trichogramma are a classic example of insects involved in pest control (Smith, 1996). This genus comprises over 200 species worldwide, which have been used to control populations of a wide range of lepidopteran pests since the 1900s (Flanders, 1930; Hassan, 1993). Despite its common use, the egg-laying preference of this genus is only partially known. For example, all Trichogramma species are often thought to have positive phototaxis (or negative geotaxis) (e.g. Brower & Cline, 1984; van Atta et al., 2015), but comprehensive studies simultaneously testing this (or other) parameter among Trichogramma species and populations remain rare. This is exactly the aim of the present study (Burte et al., 2021). Using a new experimental approach based on automatic image analysis, the authors compared the photo- and geo-tactic oviposition preference among 5 Trichogramma species from 25 populations. Their results first confirm that most Trichogramma species and populations prefer light to shade, and higher to lower positions for oviposition. Interestingly, they also reveal that the levels of preference for light and gravity show inter- and intraspecific variation (probably due to local adaptation to different strata) and that both preferences tend to relax over time. Overall, this study provides important information for improving the use of Trichogramma species as biological agents. For example, it may help to establish breeding lines adapted to the microhabitat and/or growing parts of plants on which agricultural pests lay eggs most. Similarly, it suggests that the use of multiple strains with different microhabitat selection preferences could lead to better coverage of host plants, as well as a reduction in intraspecific competition in the preferred parts. Finally, this study provides a new methodology to efficiently and automatically study oviposition preferences in Trichogramma, which could be used in other insects with a particularly small size. References Bianchi, F. J. J. A., Schellhorn, N. A. and Cunningham, S. A. (2013). Habitat functionality for the ecosystem service of pest control: reproduction and feeding sites of pests and natural enemies. Agricultural and Forest Entomology, 15, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-9563.2012.00586.x Burte V., Perez G., Ayed F., Groussier G., Mailleret L, van Oudenhove L. and Calcagno V. (2021). Up and to the light: intra- and interspecific variability of photo-and geo-tactic oviposition preferences in genus Trichogramma. bioRxiv, 2021.03.30.437671, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.30.437671 Brower, J. H. and Cline, L. D. (1984). Response of Trichogramma pretiosum and T. evanescens to Whitelight, Blacklight or NoLight Suction Traps. The Florida Entomologist, 67, 262–268. https://doi.org/10.2307/3493947 Flanders, S. E. (1930). Mass production of egg parasites of the genus Trichogramma. Hilgardia, 4, 465–501. https://doi.org/10.3733/hilg.v04n16p465 Flatt, T. and Heyland, A. (2011). Mechanisms of life history evolution: the genetics and physiology of life history traits and trade-offs. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199568765.001.0001 Gäde, G. and Goldsworthy, G. J. (2003). Insect peptide hormones: a selective review of their physiology and potential application for pest control. Pest Management Science, 59, 1063–1075. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.755 Hassan, S. A. (1993). The mass rearing and utilization of Trichogramma to control lepidopterous pests: Achievements and outlook. Pesticide Science, 37, 387–391. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.2780370412 Smith, S. M. (1996). Biological Control with Trichogramma : Advances, Successes, and Potential of Their Use. Annual Review of Entomology, 41, 375–406. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.41.010196.002111 van Atta, K. J., Potter, K. A. and Woods, H. A. (2015). Effects of UV-B on Environmental Preference and Egg Parasitization by Trichogramma Wasps (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae). Journal of Entomological Science, 50, 318–325. https://doi.org/10.18474/JES15-09.1 Wilby, A. and Thomas, M. B. (2002). Natural enemy diversity and pest control: patterns of pest emergence with agricultural intensification. Ecology Letters, 5, 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2002.00331.x | Up and to the light: intra- and interspecific variability of photo- and geo-tactic oviposition preferences in genus Trichogramma | Burte, V., Perez, G., Ayed, F. , Groussier, G., Mailleret, L., van Oudenhove, L. and Calcagno, V. | <p>Trichogramma are parasitic microwasps much used as biological control agents. The genus is known to harbor tremendous diversity, at both inter- and intra-specific levels. The successful selection of Trichogramma strains for biocontrol depends o... |  | Behavior, Biocontrol, Biodiversity, Ecology, Insecta, Parasitology, Pest management, Systematics, Terrestrial | Joël Meunier | Kévin Tougeron, Eveline C. Verhulst | 2021-04-02 16:10:28 | View |

21 Mar 2023

Population genetics of Glossina fuscipes fuscipes from southern ChadSophie Ravel, Mahamat Hissène Mahamat, Adeline Ségard, Rafael Argiles-Herrero, Jérémy Bouyer, Jean-Baptiste Rayaisse, Philippe Solano, Brahim Guihini Mollo, Mallaye Pèka, Justin Darnas, Adrien Marie Gaston Belem, Wilfrid Yoni, Camille Noûs, Thierry de Meeûs https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7763870Population genetics of tsetse, the vector of African Trypanosomiasis, helps informing strategies for control programsRecommended by Michael Lattorff based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT), or sleeping sickness, is caused by trypanosome parasites. In sub-Saharan Africa, two forms are present, Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and T. b. rhodesiense, the former responsible for 95% of reported cases. The parasites are transmitted through a vector, Genus Glossina, also known as tsetse, which means fly in Tswana, a language from southern Africa. Through a blood meal, tsetse picks up the parasite from infected humans or animals (in animals, the parasite causes Animal African Trypanosomiasis or nagana disease). Through medical interventions and vector control programs, the burden of the disease has drastically reduced over the past two decades, so the WHO neglected tropical diseases road map targets the interruption of transmission (zero cases) for 2030 (WHO 2022). Meaningful vector control programs utilize traps for the removal of animals and for surveillance, along with different methods of spraying insecticides. However, in existing HAT risk areas, it will be essential to understand the ecology of the vector species to implement control programs in a way that areas cleared from the vector will not be reinvaded from other populations. Thus, it will be crucial to understand basic population genetics parameters related to population structure and subdivision, migration frequency and distances, population sizes, and the potential for sex-biased dispersal. The authors utilize genotyping using nine highly polymorphic microsatellite markers of samples from Chad collected in differently affected regions and at different time points (Ravel et al., 2023). Two major HAT zones exist that are targeted by vector control programs, namely Madoul and Maro, while two other areas, Timbéri and Dokoutou, are free of trypanosomes. Samples were taken before vector control programs started. The sex ratio was female-biased, most strongly in Mandoul and Maro, the zones with the lowest population density. This could be explained by resource limitation, which could be the hosts for a blood meal or the sites for larviposition. Limited resources mean that females must fly further, increasing the chance that more females are caught in traps. The effective population densities of Mandoul and Maro were low. However, there was a convergence of population density and trapping density, which might be explained by the higher preservation of flies in the high-density areas of Timbéri and Dokoutou after the first round of sampling, which can only be tested using a second sampling. The dispersal distances are the highest recorded so far, especially in Mandoul and Maro, with 20-30 km per generation. However, in Timbéri and Dokoutou, which are 50 km apart, very little exchange occurs (approx. 1-2 individuals every six months). A major contributor to this is the massive destruction of habitat that started in the early 1990s and left patchily distributed and fragmented habitats. The Mandoul zone might be safe from reinvasion after eradication, as for a successful re-establishment, either a pair of a female and male or a pregnant female are required. As the trypanosome prevalence amongst humans was 0.02 and of tsetse 0.06 (Ibrahim et al., 2021) before interventions began, medical interventions and vector control might have further reduced these levels, making a reinvasion and subsequent re-establishment of HAT very unlikely. Maro is close to the border of the Central African Republic, and the area has not been well investigated concerning refugee populations of tsetse, which could contribute to a reinvasion of the Maro zone. The higher level of genetic heterogeneity of the Maro population indicates that invasions from neighboring populations are already ongoing. This immigration could also be the reason for not detecting the bottleneck signature in the Maro population. The two HAT areas need different levels of attention while implementing vector eradication programs. While Madoul is relatively safe against reinvasion, Maro needs another type of attention, as frequent and persistent immigration might counteract eradication efforts. Thus, it is recommended that continuous tsetse suppression needs to be implemented in Maro. This study shows nicely that an in-depth knowledge of the processes within and between populations is needed to understand how these populations behave. This can be used to extrapolate, make predictions, and inform the organisations implementing vector control programs to include valuable adjustments, as in the case of Maro. Such integrative approaches can help prevent the failure of programs, potentially saving costs and preventing infections of humans and animals who might die if not treated. References Ibrahim MAM, Weber JS, Ngomtcho SCH, Signaboubo D, Berger P, Hassane HM, Kelm S (2021) Diversity of trypanosomes in humans and cattle in the HAT foci Mandoul and Maro, Southern Chad- Southern Chad-A matter of concern for zoonotic potential? PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 15, e000 323. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0009323 Ravel S, Mahamat MH, Ségard A, Argiles-Herrero R, Bouyer J, Rayaisse JB, Solano P, Mollo BG, Pèka M, Darnas J, Belem AMG, Yoni W, Noûs C, de Meeûs T (2023) Population genetics of Glossina fuscipes fuscipes from southern Chad. Zenodo, ver. 9 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7763870 WHO (2022) Trypanosomiasis, human African (sleeping sickness). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/trypanosomiasis-human-african-(sleeping-sickness), retrieved 17. March 2023 | Population genetics of Glossina fuscipes fuscipes from southern Chad | Sophie Ravel, Mahamat Hissène Mahamat, Adeline Ségard, Rafael Argiles-Herrero, Jérémy Bouyer, Jean-Baptiste Rayaisse, Philippe Solano, Brahim Guihini Mollo, Mallaye Pèka, Justin Darnas, Adrien Marie Gaston Belem, Wilfrid Yoni, Camille Noûs, Thierr... | <p>In Subsaharan Africa, tsetse flies (genus Glossina) are vectors of trypanosomes causing Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT) and Animal African Trypanosomosis (AAT). Some foci of HAT persist in Southern Chad, where a program of tsetse control wa... | Biology, Ecology, Evolution, Genetics/Genomics, Insecta, Medical entomology, Parasitology, Pest management, Veterinary entomology | Michael Lattorff | Audrey Bras | 2022-04-22 11:25:24 | View | |

01 Jul 2020

Sub-lethal insecticide exposure affects host biting efficiency of Kdr-resistant Anopheles gambiaeMalal Mamadou Diop, Fabrice Chandre, Marie Rossignol, Angelique Porciani, Mathieu Chateau, Nicolas Moiroux, Cedric Pennetier https://doi.org/10.1101/653980kdr homozygous resistant An. gambiae displayed enhanced feeding success when exposed to permethrin Insect-Treated NetsRecommended by Adrian Diaz based on reviews by Thomas Guillemaud, Niels Verhulst, Etienne Bilgo and 1 anonymous reviewerMalaria is a vector-borne parasitic disease found in 91 countries with an estimated of 228 million cases occurred worldwide during 2018. The 93% (213 million) of those cases were reported in the African Region (WHO 2019). Six species of Plasmodium parasites can produce the disease but only P. falciparum and P. vivax are the predominant species globally. More than 40 species of Anopheles mosquitoes are important malaria vectors (Asley et al. 2018). Intrinsic (genetic background, parasite susceptibility) and extrinsic (feeding host preference, host diversity and availability, mosquito abundance) factors affect the capacity of mosquitoes to vector the disease (Macdonald 1952). Malaria is prevented by chemoprophylaxis, vaccination, bite-avoidance and vector-control measures. The mainstays of vector control are long-lasting insecticide (pyrethroid) treated nets and indoor residual spraying with insecticides (Asley et al. 2018). The widespread use of pyrethroid insecticides forced the emergence of insecticide resistance in malaria vectors reducing the insecticidal effect. Mosquitoes can modify their behaviour avoiding insecticide contact and so potentially reducing vector control tools efficacy. In this sense, Diop et al. (2020) investigated whether pre-exposure to an Insecticide-Treated Net (ITN) modulates the mosquito ability to take a blood meal in Anopheles gambiae. By means of video recording experiments the authors analyzed how the feeding/bitting behaviour was affected by kdr mutation genotypes (homozygous susceptible – SS-, heterozygotes -RS- and homozygous resistant -RR-) when exposed to two different insecticides (permethrin and deltamethrin). According to the results, the blood-feeding success did not differ between the three genotypes in the absence of insecticide exposure. However, authors observed differences in the feeding duration and blood meal size. In example, RR mosquitoes spent less time taking their blood meal than RS and SS. On the other hand, RS mosquitoes took higher blood volumes than RR females. These differences can affect the mosquito fitness by decreasing/increasing the likelihood to be killed by the host defensive behavior or increase the oogenesis so enhancing fecundity. Regarding the effect of exposition to insecticides authors detected a strong relationship between kdr genotype and Knock Down (KD) phenotype when mosquitoes were exposed to Permethrin. Previously, the authors have evidenced that RR mosquitoes prefer a host protected by a permethrin-treated net rather than an untreated net and that heterozygotes RS mosquitoes have a remarkable ability to find a hole into a bet net (Diop et al. 2015, Porciani et al. 2017). With data here obtained, they demonstrated that kdr homozygous resistant An. gambiae displayed enhanced feeding success when exposed to permethrin ITN. The changes observed in the feeding/biting mosquito behaviour can affect their fitness shaping the evolution of the insecticide resistance in mosquitoes’ natural populations. Moreover, this may also alter parasite transmission dynamics by modifying vector/host interactions and so vector capacity. References World Health Organization (2019). World malaria report 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. ISBN 978-92-4-156572-1 | Sub-lethal insecticide exposure affects host biting efficiency of Kdr-resistant Anopheles gambiae | Malal Mamadou Diop, Fabrice Chandre, Marie Rossignol, Angelique Porciani, Mathieu Chateau, Nicolas Moiroux, Cedric Pennetier | <p>The massive use of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) has drastically changed the environment for malaria vector mosquitoes, challenging their host-seeking behaviour and biting success. Here, we investigated the effect of a brief exposure to an IT... |  | Behavior, Ecology, Evolution, Medical entomology, Pesticide resistance | Adrian Diaz | Anonymous | 2019-05-29 19:40:25 | View |

03 Jul 2020

The 'Noble false widow' spider Steatoda nobilis is an emerging public health and ecological threatHambler, C. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/axbd4How the noble false widow spider Steatoda nobilis can turn out to be a rising public health and ecological concernRecommended by Etienne Bilgo based on reviews by Michel Dugon and 2 anonymous reviewers"The noble false widow spider Steatoda nobilis is an emerging public health and ecological threat" by Clive Hambler (2020) is an appealing article discussing important aspects of the ecology and distribution of a medically significant spider, and the health concerns it raises. References [1] Hambler, C. (2020). The “Noble false widow” spider Steatoda nobilis is an emerging public health and ecological threat. OSF Preprints, axbd4, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. doi: 10.31219/osf.io/axbd4 | The 'Noble false widow' spider Steatoda nobilis is an emerging public health and ecological threat | Hambler, C. | <p>*Steatoda nobilis*, the 'Noble false widow' spider, has undergone massive population growth in southern Britain and Ireland, at least since 1990. It is greatly under-recorded in Britain and possibly globally. Now often the dominant spider on an... |  | Arachnids, Behavior, Biogeography, Biological invasions, Conservation biology, Demography/population dynamics, Ecology, Medical entomology, Methodology, Pest management, Toxicology, Veterinary entomology | Etienne Bilgo | 2019-06-28 18:26:05 | View | |

10 Jan 2020

Culex saltanensis and Culex interfor (Diptera: Culicidae) are susceptible and competent to transmit St. Louis encephalitis virus (Flavivirus: Flaviviridae) in central ArgentinaBeranek MD, Quaglia AI, Peralta GC, Flores FS, Stein M, Diaz LA, Almirón WR and Contigiani MS https://doi.org/10.1101/722579Multiple vector species may be responsible for transmission of Saint Louis Encephalatis Virus in ArgentinaRecommended by Anna Cohuet based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersMedical and veterinary entomology is a discipline that deals with the role of insects on human and animal health. A primary objective is the identification of vectors that transmit pathogens. This is the aim of Beranek and co-authors in their study [1]. They focus on mosquito vector species responsible for transmission of St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV), an arbovirus that circulates in avian species but can incidentally occur in dead end mammal hosts such as humans, inducing symptoms and sometimes fatalities. Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus is known as the most common vector, but other species are suspected to also participate in transmission. Among them Culex saltanensis and Culex interfor have been found to be infected by the virus in the context of outbreaks. The fact that field collected mosquitoes carry virus particles is not evidence for their vector competence: indeed to be a competent vector, the mosquito must not only carry the virus, but also the virus must be able to replicate within the vector, overcome multiple barriers (until the salivary glands) and be present at sufficient titre within the saliva. This paper describes the experiments implemented to evaluate the vector competence of Cx. saltanensis and Cx. interfor from ingestion of SLEV to release within the saliva. Females emerged from field-collected eggs of Cx. pipiens quinquefasciatus, Cx. saltanensis and Cx. interfor were allowed to feed on SLEV infected chicks and viral development was measured by using (i) the infection rate (presence/absence of virus in the mosquito abdomen), (ii) the dissemination rate (presence/absence of virus in mosquito legs), and (iii) the transmission rate (presence/absence of virus in mosquito saliva). The sample size for each species is limited because of difficulties for collecting, feeding and maintaining large numbers of individuals from field populations, however the results are sufficient to show that this strain of SLEV is able to disseminate and be expelled in the saliva of mosquitoes of the three species at similar viral loads. This work therefore provides evidence that Cx saltanensis and Cx interfor are competent species for SLEV to complete its life-cycle. Vector competence does not directly correlate with the ability to transmit in real life as the actual vectorial capacity also depends on the contact between the infectious vertebrate hosts, the mosquito life expectancy and the extrinsic incubation period of the viruses. The present study does not deal with these characteristics, which remain to be investigated to complete the picture of the role of Cx saltanensis and Cx interfor in SLEV transmission. However, this study provides proof of principle that that SLEV can complete it’s life-cycle in Cx saltanensis and Cx interfor. Combined with previous knowledge on their feeding preference, this highlights their potential role as bridge vectors between birds and mammals. These results have important implications for epidemiological forecasting and disease management. Public health strategies should consider the diversity of vectors in surveillance and control of SLEV. References | Culex saltanensis and Culex interfor (Diptera: Culicidae) are susceptible and competent to transmit St. Louis encephalitis virus (Flavivirus: Flaviviridae) in central Argentina | Beranek MD, Quaglia AI, Peralta GC, Flores FS, Stein M, Diaz LA, Almirón WR and Contigiani MS | <p>Infectious diseases caused by mosquito-borne viruses constitute health and economic problems worldwide. St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV) is endemic and autochthonous in the American continent. Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus is the primary ur... |  | Medical entomology | Anna Cohuet | 2019-08-03 00:56:38 | View | |

22 Jul 2020

The open bar is closed: restructuration of a native parasitoid community following successful control of an invasive pest.David Muru, Nicolas Borowiec, Marcel Thaon, Nicolas Ris, Madalina Ionela Viciriuc, Sylvie Warot, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.20.884908Raise and fall of an invasive pest and consequences for native parasitoid communitiesRecommended by Stefaniya Kamenova based on reviews by Kévin Tougeron and Miguel González Ximénez de EmbúnHost-parasitoid interactions have been the focus of extensive ecological research for decades. One the of the major reasons is the importance host-parasitoid interactions play for the biological control of crop pests. Parasitoids are the main natural regulators for a large number of economically important pest insects, and in many cases they could be the only viable crop protection strategy. Parasitoids are also integral part of complex food webs whose structure and diversity display large spatio-temporal variations [1-3]. With the increasing globalization of human activities, the generalized spread and establishment of invasive species is a major cause of disruption in local community and food web spatio-temporal dynamics. In particular, the deliberate introduction of non-native parasitoids as part of biological control programs, aiming the suppression of established, and also highly invasive crop pests, is a common practice with potentially significant, yet poorly understood effects on local food web dynamics (e.g. [4]). References [1] Eveleigh ES, McCann KS, McCarthy PC, Pollock SJ, Lucarotti CJ, Morin B, McDougall GA, Strongman DB, Huber JT, Umbanhowar J, Faria LDB (2007). Fluctuations in density of an outbreak species drive diversity cascades in food webs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 16976-16981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704301104 | The open bar is closed: restructuration of a native parasitoid community following successful control of an invasive pest. | David Muru, Nicolas Borowiec, Marcel Thaon, Nicolas Ris, Madalina Ionela Viciriuc, Sylvie Warot, Elodie Vercken | <p>The rise of the Asian chestnut gall wasp *Dryocosmus kuriphilus* in France has benefited the native community of parasitoids originally associated with oak gall wasps by becoming an additional trophic subsidy and therefore perturbing population... |  | Biocontrol, Biological invasions, Ecology, Insecta | Stefaniya Kamenova | 2019-12-31 09:08:49 | View | |

24 Jun 2022

Dopamine pathway characterization during the reproductive mode switch in the pea aphidGaël Le Trionnaire, Sylvie Hudaverdian, Gautier Richard, Sylvie Tanguy, Florence Gleonnec, Nathalie Prunier-Leterme, Jean-Pierre Gauthier, Denis Tagu https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.10.984989In search of the links between environmental signals and polyphenismRecommended by Mathieu Joron based on reviews by Antonia Monteiro and 2 anonymous reviewersPolyphenisms offer an opportunity to study the links between phenotype, development, and environment in a controlled genomic context (Simpson, Sword, & Lo, 2011). In organisms with short generation times, individuals living and developing in different seasons encounter different environmental conditions. Adaptive plasticity allows them to express different phenotypes in response to seasonal cues, such as temperature or photoperiod. Such phenotypes can be morphological variants, for instance displaying different wing patterns as seen in butterflies (Brakefield & Larsen, 1984; Nijhout, 1991; Windig, 1999), or physiological variants, characterized for instance by direct development vs winter diapause in temperate insects (Dalin & Nylin, 2012; Lindestad, Wheat, Nylin, & Gotthard, 2019; Shearer et al., 2016). Many aphids display cyclical parthenogenesis, a remarkable seasonal polyphenism for reproductive mode (Tagu, Sabater-Muñoz, & Simon, 2005), also sometimes coupled with wing polyphenism (Braendle, Friebe, Caillaud, & Stern, 2005), which allows them to switch between parthenogenesis during spring and summer to sexual reproduction and the production of diapausing eggs before winter. In the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum, photoperiod shortening results in the production, by parthenogenetic females, of embryos developing into the parthenogenetic mothers of sexual individuals. The link between parthenogenetic reproduction and sexual reproduction, therefore, occurs over two generations, changing from a parthenogenetic form producing parthenogenetic females (virginoparae), to a parthenogenetic form producing sexual offspring (sexuparae), and finally sexual forms producing overwintering eggs (Le Trionnaire et al., 2022). The molecular basis for the transduction of the environmental signal into reproductive changes is still unknown, but the dopamine pathway is an interesting candidate. Form-specific expression of certain genes in the dopamine pathway occurs downstream of the perception of the seasonal cue, notably with a marked decrease in the heads of embryos reared under short-day conditions and destined to become sexuparae. Dopamine has multiple roles during development, with one mode of action in cuticle melanization and sclerotization, and a neurological role as a synaptic neurotransmitter. Both modes of action might be envisioned to contribute functionally to the perception and transduction of environmental signals. In this study, Le Trionnaire and colleagues aim at clarifying this role in the pea aphid (Le Trionnaire et al., 2022). Using quantitative RT-PCR, RNA-seq, and in situ hybridization of RNA probes, they surveyed the timing and spatial patterns of expression of dopamine pathway genes during the development of different stages of embryo to larvae reared under long and short-day conditions, and destined to become virginoparae or sexuparae females, respectively. The genes involved in the synaptic release of dopamine generally did not show differences in expression between photoperiodic treatments. By contrast, pale and ddc, two genes acting upstream of dopamine production, generally tended to show a downregulation in sexuparare embryo, as well as genes involved in cuticle development and interacting with the dopamine pathway. The downregulation of dopamine pathway genes observed in the heads of sexuparare juveniles is already detectable at the embryonic stage, suggesting embryos might be sensing environmental cues leading them to differentiate into sexuparae females. The way pale and ddc expression differences could influence environmental sensitivity is still unclear. The results suggest that a cuticle phenotype specifically in the heads of larvae could be explored, perhaps in the form of a reduction in cuticle sclerotization and melanization which might allow photoperiod shortening to be perceived and act on development. Although its causality might be either way, such a link would be exciting to investigate, yet the existence of cuticle differences between the two reproductive types is still a hypothesis to be tested. The lack of differences in the expression of synaptic release genes for dopamine might seem to indicate that the plastic response to photoperiod is not mediated via neurological roles. Yet, this does not rule out the role of decreasing levels of dopamine in mediating this response in the central nervous system of embryos, even if the genes regulating synaptic release are equally expressed. To test for a direct role of ddc in regulating the reproductive fate of embryos, the authors have generated CrispR-Cas9 knockout mutants. Those mutants displayed egg cuticle melanization, but with lethal effects, precluding testing the effect of ddc at later stages in development. Gene manipulation becomes feasible in the pea aphid, opening up certain avenues for understanding the roles of other genes during development. This study adds nicely to our understanding of the intricate changes in gene expression involved in polyphenism. But it also shows the complexity of deciphering the links between environmental perception and changes in physiology, which mobilise multiple interacting gene networks. In the era of manipulative genetics, this study also stresses the importance of understanding the traits and phenotypes affected by individual genes, which now seems essential to piece the puzzle together. References Braendle C, Friebe I, Caillaud MC, Stern DL (2005) Genetic variation for an aphid wing polyphenism is genetically linked to a naturally occurring wing polymorphism. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 272, 657–664. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2004.2995 Brakefield PM, Larsen TB (1984) The evolutionary significance of dry and wet season forms in some tropical butterflies. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 22, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.1984.tb00795.x Dalin P, Nylin S (2012) Host-plant quality adaptively affects the diapause threshold: evidence from leaf beetles in willow plantations. Ecological Entomology, 37, 490–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2311.2012.01387.x Le Trionnaire G, Hudaverdian S, Richard G, Tanguy S, Gleonnec F, Prunier-Leterme N, Gauthier J-P, Tagu D (2022) Dopamine pathway characterization during the reproductive mode switch in the pea aphid. bioRxiv, 2020.03.10.984989, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.10.984989 Lindestad O, Wheat CW, Nylin S, Gotthard K (2019) Local adaptation of photoperiodic plasticity maintains life cycle variation within latitudes in a butterfly. Ecology, 100, e02550. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2550 Nijhout HF (1991). The development and evolution of butterfly wing patterns. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. Shearer PW, West JD, Walton VM, Brown PH, Svetec N, Chiu JC (2016) Seasonal cues induce phenotypic plasticity of Drosophila suzukii to enhance winter survival. BMC Ecology, 16, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-016-0070-3 Simpson SJ, Sword GA, Lo N (2011) Polyphenism in Insects. Current Biology, 21, R738–R749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.006 Tagu D, Sabater-Muñoz B, Simon J-C (2005) Deciphering reproductive polyphenism in aphids. Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, 48, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2005.9652172 Windig JJ (1999) Trade-offs between melanization, development time and adult size in Inachis io and Araschnia levana (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae)? Heredity, 82, 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6884510 | Dopamine pathway characterization during the reproductive mode switch in the pea aphid | Gaël Le Trionnaire, Sylvie Hudaverdian, Gautier Richard, Sylvie Tanguy, Florence Gleonnec, Nathalie Prunier-Leterme, Jean-Pierre Gauthier, Denis Tagu | <p>Aphids are major pests of most of the crops worldwide. Such a success is largely explained by the remarkable plasticity of their reproductive mode. They reproduce efficiently by viviparous parthenogenesis during spring and summer generating imp... |  | Development, Genetics/Genomics, Insecta, Molecular biology | Mathieu Joron | 2020-03-13 13:01:44 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Dominique Adriaens

Ellen Decaestecker

Benoit Facon

Isabelle Schon

Emmanuel Toussaint

Bertanne Visser