Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

27 Apr 2023

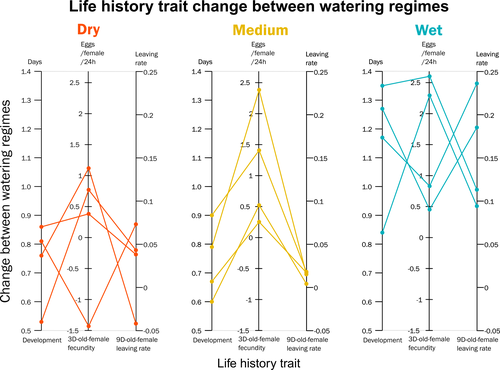

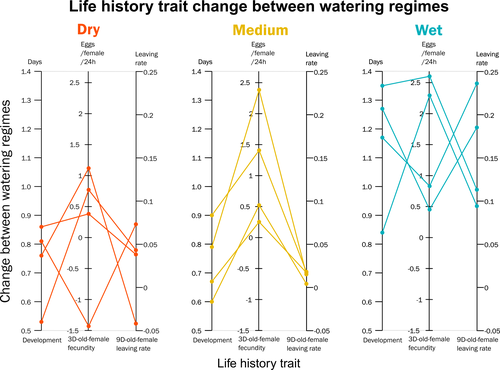

Climate of origin influences how a herbivorous mite responds to drought-stressed host plantsAlain Migeon, Philippe Auger, Odile Fossati-Gaschignard, Ruth A. Hufbauer, Maëva Miranda, Ghais Zriki, Maria Navajas https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.21.465244Not all spider-mites respond in the same way to droughtRecommended by Inês Fragata and Raul Costa-Pereira based on reviews by Bastien Castagneyrol and 2 anonymous reviewersBiotic interactions are often shaped by abiotic factors (Liu and Gaines 2022). Although this notion is not new in ecology and evolutionary biology, we are still far from a thorough understanding of how biotic interactions change along abiotic gradients in space and time. This is particularly challenging because abiotic factors can affect organisms and their interactions in multiple – direct or indirect – ways. For example, because abiotic conditions strongly determine how energy enters biological systems via producers, their effects can propagate through entire food webs, from the bottom to the top (O’Connor 2009, Gilbert et al 2019). Understanding how biological diversity - both within and across species - is shaped by the indirect effects of environmental conditions is a timely question as climate change and anthropogenic activities have been altering temperature and water availability across different ecosystems. Motivated by the current water crisis and severe droughts predicted for the near future worldwide (du Plessis 2019), Migeon et al. (2023) investigated how water limitation on producers scales up to affect life-history patterns of a widespread crop pest, the spider mite Tetranychus urticae. The authors sampled spider mite populations (n = 12) along a striking gradient of climatic conditions (>16 degrees of latitude) in Europe. After letting mites acclimate to lab conditions for several generations, the authors performed a common garden experiment to quantify how the life-history traits of mite populations from different locations respond to drought stress in their host plants. Curiously, the authors found that, when reared on drought-stressed plants, mites tended to develop faster, had higher fecundity and lower dispersion rates. This response was in line with some results obtained previously with Tetranychus species (e.g. Ximénez-Embun et al 2016). Importantly, despite some experimental caveats in the experimental design, which makes it difficult to completely disentangle the specific effects of location vs. environmental noise, results suggest the climate that populations originally experienced was also an important determinant of the plastic response in these herbivores. In fact, populations from wetter and colder regions showed a steeper change in drought response, while populations from arid climates showed a shallower response. This interesting result suggests the importance of intraspecific (between-populations) variation in the response to drought, which might be explained by the climatic heterogeneity in space throughout the evolutionary history of different populations. These results become even more important in our rapidly changing world, highlighting the importance of considering genetic variation (and conditions that generate it) when predicting plastic and evolutionary responses to stressful conditions. du Plessis, A. (2019). Current and Future Water Scarcity and Stress. In: Water as an Inescapable Risk. Springer Water. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03186-2 | Climate of origin influences how a herbivorous mite responds to drought-stressed host plants | Alain Migeon, Philippe Auger, Odile Fossati-Gaschignard, Ruth A. Hufbauer, Maëva Miranda, Ghais Zriki, Maria Navajas | <p style="text-align: justify;">Drought associated with climate change can stress plants, altering their interactions with phytophagous arthropods. Drought not only impacts cultivated plants but also their parasites, which in some cases are favore... |  | Acari, Ecology, Life histories | Inês Fragata | 2021-10-22 14:56:03 | View | |

27 Apr 2023

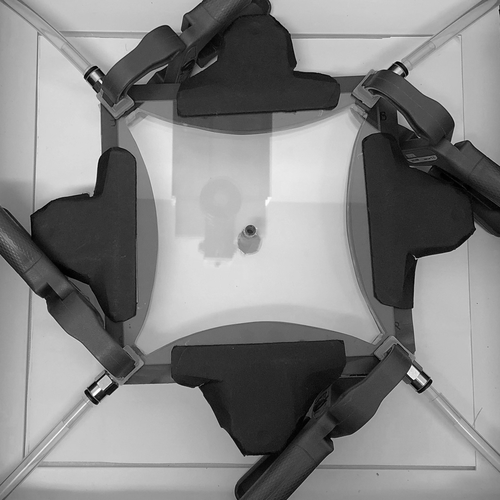

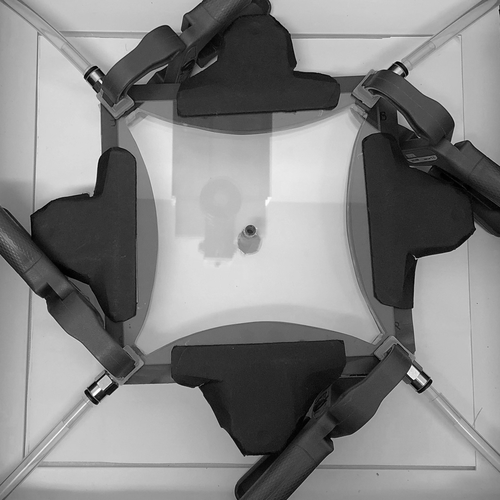

Brood thermoregulation effectivenessis positively linked to the amount of brood but not to the number of bees in honeybee coloniesUgoline Godeau, Maryline Pioz, Olivier Martin, Charlotte Rüger, Didier Crauser, Yves Le Conte, Mickael Henry, Cédric Alaux https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/9mwyePrecision and accuracy of honeybee thermoregulationRecommended by Michael Lattorff based on reviews by Jakob Wegener and Christopher Mayack based on reviews by Jakob Wegener and Christopher Mayack

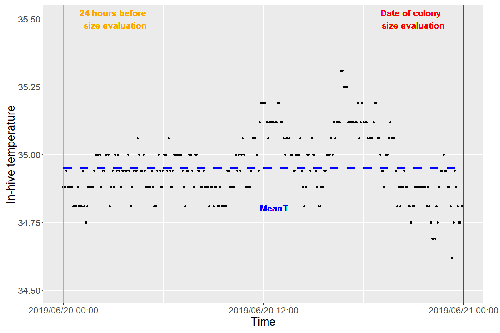

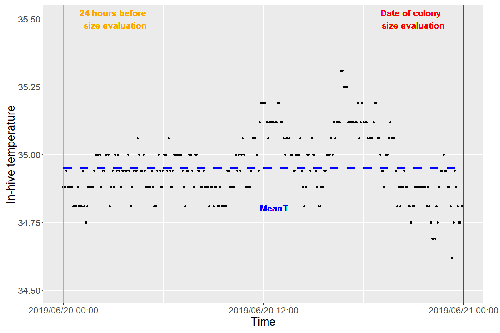

The Western honeybee, Apis mellifera L., is one of the best-studied social insects. It shows a reproductive division of labour, cooperative brood care, and age-related polyethism. Furthermore, honeybees regulate the temperature in the hive. Although bees are invertebrates that are usually ectothermic, this is still true for individual worker bees, but the colony maintains a very narrow range of temperature, especially within the brood nest. This is quite important as the development of individuals is dependent on ambient temperature, with higher temperatures resulting in accelerated development and vice versa. In honeybees, a feedback mechanism couples developmental temperature and the foraging behaviour of the colony and the future population development (Tautz et al., 2003). Bees raised under lower temperatures are more likely to perform in-hive tasks, while bees raised under higher temperatures are better foragers. To maintain optimal levels of worker population growth and foraging rates, it is adaptive to regulate temperature to ensure optimal levels of developing brood. Moreover, this allows honeybees to decouple the internal developmental processes from ambient temperatures enhancing the ecological success of the species. In every system of thermoregulation, whether it is endothermic under the utilization of energetic resources as in mammals or the honeybee or ectothermic as in lower vertebrates and invertebrates through differential exposure to varying environmental temperature gradients, there is a need for precision (low variability) and accuracy (hitting the target temperature). However, in honeybees, the temperature is regulated by workers through muscle contraction and fanning of the wings and thus, a higher number of workers could be better at achieving precise and accurate temperature within the brood nest. Alternatively, the amount of brood could trigger responses with more brood available, a need for more precise and accurate temperature control. The authors aimed at testing these two important factors on the precision and accuracy of within-colony temperature regulation by monitoring 28 colonies equipped with temperature sensors for two years (Godeau et al., 2023). They found that the number of brood cells predicted the mean temperature (accuracy of thermoregulation). Other environmental factors had a small effect. However, the model incorporating these factors was weak in predicting the temperature as it overestimated temperatures in lower ranges and underestimated temperatures in higher ranges. In contrast, the variability of the target temperature (precision of thermoregulation) was positively affected by the external temperature, while all other factors did not show a significant effect. Again, the model was weak in predicting the data. Overall colony size measured in categories of the number of workers and the number of brood cells did not show major differences in variability of the mean temperature, but a slight positive effect for the number of bees on the mean temperature. Unfortunately, the temperature was a poor predictor of colony size. The latter is important as the remote control of beehives using Internet of Things (IoT) technologies get more and more incorporated into beekeeping management. These IoT technologies and their success are dependent on good proxies for the control of the status of the colony. Amongst the factors to monitor, the colony size (number of bees and/or amount of brood) is extremely important, but temperature measurements alone will not allow us to predict colony sizes. Nevertheless, this study showed clearly that the number of brood cells is a crucial factor for the accuracy of thermoregulation in the beehive, while ambient temperature affects the precision of thermoregulation. In the view of climate change, the latter factor seems to be important, as more extreme environmental conditions in the future call for measures of mitigation to ensure the proper functioning of the bee colony, including the maintenance of homeostatic conditions inside of the nest to ensure the delivery of the ecosystem service of pollination. REFERENCES Godeau U, Pioz M, Martin O, Rüger C, Crauser D, Le Conte Y, Henry M, Alaux C (2023) Brood thermoregulation effectiveness is positively linked to the amount of brood but not to the number of bees in honeybee colonies. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/9mwye Tautz J, Maier S, Claudia Groh C, Wolfgang Rössler W, Brockmann A (2003) Behavioral performance in adult honey bees is influenced by the temperature experienced during their pupal development. PNAS 100: 7343–7347. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1232346100 | Brood thermoregulation effectivenessis positively linked to the amount of brood but not to the number of bees in honeybee colonies | Ugoline Godeau, Maryline Pioz, Olivier Martin, Charlotte Rüger, Didier Crauser, Yves Le Conte, Mickael Henry, Cédric Alaux | <p style="text-align: justify;">To ensure the optimal development of brood, a honeybee colony needs to regulate its temperature within a certain range of values (thermoregulation), regardless of environmental changes in biotic and abiotic factors.... |  | Biology, Conservation biology, Demography/population dynamics, Ecology, Insecta | Michael Lattorff | Mauricio Daniel Beranek | 2022-07-06 09:20:10 | View |

26 Apr 2023

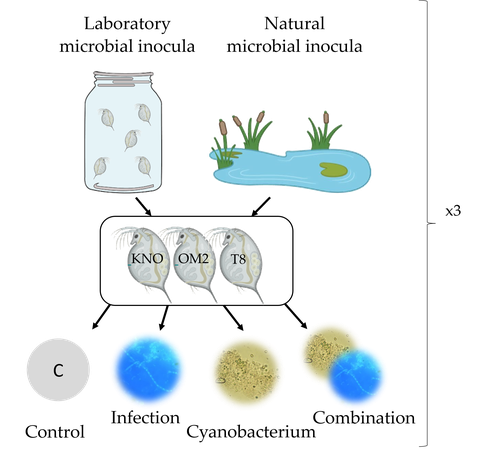

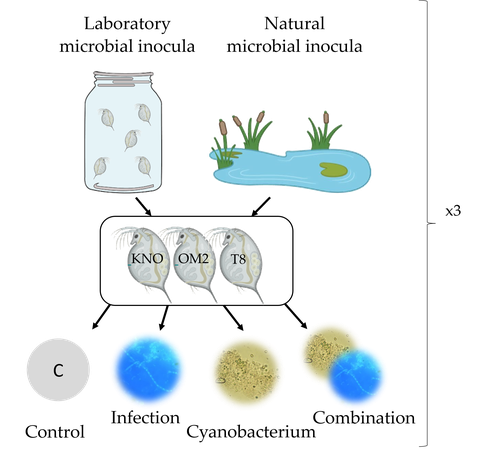

Microbiome mediated tolerance to biotic stressors: a case study of the interaction between a toxic cyanobacterium and an oomycete-like infection in Daphnia magnaShira Houwenhuyse*, Lore Bulteel*, Isabel Vanoverberghe, Anna Krzynowek, Naina Goel, Manon Coone, Silke Van den Wyngaert, Arne Sinnesael, Robby Stoks & Ellen Decaestecker https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/9n4mgMulti-stress responses depend on the microbiome in the planktonic crustacean DaphniaRecommended by Bertanne Visser and Mathilde Scheifler based on reviews by Natacha Kremer and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Natacha Kremer and 2 anonymous reviewers

The critical role that gut microbiota play in many aspects of an animal’s life, including pathogen resistance, detoxification, digestion, and nutritional physiology, is becoming more and more apparent (Engel and Moran 2013; Lindsay et al., 2020). Gut microbiota recruitment and maintenance can be largely affected by the surrounding environment (Chandler et al., 2011; Callens et al., 2020). The environment may thus dictate gut microbiota composition and diversity, which in turn can affect organismal responses to stress. Only few studies have, however, taken the gut microbiota into account to estimate life histories in response to multiple stressors in aquatic systems (Macke et al., 2016). Houwenhuyse et al., investigate how the microbiome affects life histories in response to ecologically relevant single and multiple biotic stressors (an oomycete-like parasite, and a toxic cyanobacterium) in Daphnia magna (Houwenhuyse et al., 2023). Daphnia is an excellent model, because this aquatic system lends itself extremely well for gut microbiota transplantation and manipulation. This is due to the possibility to sterilize eggs (making them free of bacteria), horizontal transmission of bacteria from the environment, and the relative ease of culturing genetically similar Daphnia clones in large numbers. The authors use an elegant experimental design to show that the Daphnia gut microbial community differs when derived from a laboratory versus natural inoculum, the latter being more diverse. The authors subsequently show that key life history traits (survival, fecundity, and body size) depend on the stressors (and combination thereof), the microbiota (structure and diversity), and Daphnia genotype. A key finding is that Daphnia exposed to both biotic stressors show an antagonistic interaction effect on survival (being higher), but only in individuals containing laboratory gut microbiota. The exact mechanism remains to be determined, but the authors propose several interesting hypotheses as to why Daphnia with more diverse gut microbiota do less well. This could be due, for example, to increased inter-microbe competition or an increased chance of contracting opportunistic, parasitic bacteria. For Daphnia with less diverse laboratory gut microbiota, a monopolizing species may be particularly beneficial for stress tolerance. Alongside these interesting findings, the paper also provides extensive information about the gut microbiota composition (available in the supplementary files), which is a very useful resource for other researchers. Overall, this study reveals that multiple, interacting factors affect the performance of Daphnia under stressful conditions. Of importance is that laboratory studies may be based on simpler microbiota systems, meaning that stress responses measured in the laboratory may not accurately reflect what is happening in nature. REFERENCES Callens M, De Meester L, Muylaert K, Mukherjee S, Decaestecker E. The bacterioplankton community composition and a host genotype dependent occurrence of taxa shape the Daphnia magna gut bacterial community. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2020;96(8):fiaa128. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiaa128 Chandler JA, Lang JM, Bhatnagar S, Eisen JA, Kopp A. Bacterial communities of diverse Drosophila species: ecological context of a host-microbe model system. PLOS Genetics. 2011;7(9):e1002272. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002272 Engel P, Moran NA. The gut microbiota of insects - diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2013;37(5):699-735. https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6976.12025 Houwenhuyse S, Bulteel L, Vanoverberghe I, Krzynowek A, Goel N et al. Microbiome mediated tolerance to biotic stressors: a case study of the interaction between a toxic cyanobacterium and an oomycete-like infection in Daphnia magna. 2023. OSF, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/9n4mg Lindsay EC, Metcalfe NB, Llewellyn MS. The potential role of the gut microbiota in shaping host energetics and metabolic rate. Journal of Animal Ecology. 2020;89(11):2415-2426. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13327 Macke E, Tasiemski A, Massol F, Callens M, Decaestecker E. Life history and eco-evolutionary dynamics in light of the gut microbiota. Oikos. 2017;126(4):508-531. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.03900 | Microbiome mediated tolerance to biotic stressors: a case study of the interaction between a toxic cyanobacterium and an oomycete-like infection in *Daphnia magna* | Shira Houwenhuyse*, Lore Bulteel*, Isabel Vanoverberghe, Anna Krzynowek, Naina Goel, Manon Coone, Silke Van den Wyngaert, Arne Sinnesael, Robby Stoks & Ellen Decaestecker | <p style="text-align: justify;">Organisms are increasingly facing multiple, potentially interacting stressors in natural populations. The ability of populations coping with combined stressors depends on their tolerance to individual stressors and ... |  | Aquatic, Biology, Crustacea, Ecology, Life histories, Symbiosis | Bertanne Visser | 2021-05-17 16:18:18 | View | |

21 Mar 2023

Population genetics of Glossina fuscipes fuscipes from southern ChadSophie Ravel, Mahamat Hissène Mahamat, Adeline Ségard, Rafael Argiles-Herrero, Jérémy Bouyer, Jean-Baptiste Rayaisse, Philippe Solano, Brahim Guihini Mollo, Mallaye Pèka, Justin Darnas, Adrien Marie Gaston Belem, Wilfrid Yoni, Camille Noûs, Thierry de Meeûs https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7763870Population genetics of tsetse, the vector of African Trypanosomiasis, helps informing strategies for control programsRecommended by Michael Lattorff based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT), or sleeping sickness, is caused by trypanosome parasites. In sub-Saharan Africa, two forms are present, Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and T. b. rhodesiense, the former responsible for 95% of reported cases. The parasites are transmitted through a vector, Genus Glossina, also known as tsetse, which means fly in Tswana, a language from southern Africa. Through a blood meal, tsetse picks up the parasite from infected humans or animals (in animals, the parasite causes Animal African Trypanosomiasis or nagana disease). Through medical interventions and vector control programs, the burden of the disease has drastically reduced over the past two decades, so the WHO neglected tropical diseases road map targets the interruption of transmission (zero cases) for 2030 (WHO 2022). Meaningful vector control programs utilize traps for the removal of animals and for surveillance, along with different methods of spraying insecticides. However, in existing HAT risk areas, it will be essential to understand the ecology of the vector species to implement control programs in a way that areas cleared from the vector will not be reinvaded from other populations. Thus, it will be crucial to understand basic population genetics parameters related to population structure and subdivision, migration frequency and distances, population sizes, and the potential for sex-biased dispersal. The authors utilize genotyping using nine highly polymorphic microsatellite markers of samples from Chad collected in differently affected regions and at different time points (Ravel et al., 2023). Two major HAT zones exist that are targeted by vector control programs, namely Madoul and Maro, while two other areas, Timbéri and Dokoutou, are free of trypanosomes. Samples were taken before vector control programs started. The sex ratio was female-biased, most strongly in Mandoul and Maro, the zones with the lowest population density. This could be explained by resource limitation, which could be the hosts for a blood meal or the sites for larviposition. Limited resources mean that females must fly further, increasing the chance that more females are caught in traps. The effective population densities of Mandoul and Maro were low. However, there was a convergence of population density and trapping density, which might be explained by the higher preservation of flies in the high-density areas of Timbéri and Dokoutou after the first round of sampling, which can only be tested using a second sampling. The dispersal distances are the highest recorded so far, especially in Mandoul and Maro, with 20-30 km per generation. However, in Timbéri and Dokoutou, which are 50 km apart, very little exchange occurs (approx. 1-2 individuals every six months). A major contributor to this is the massive destruction of habitat that started in the early 1990s and left patchily distributed and fragmented habitats. The Mandoul zone might be safe from reinvasion after eradication, as for a successful re-establishment, either a pair of a female and male or a pregnant female are required. As the trypanosome prevalence amongst humans was 0.02 and of tsetse 0.06 (Ibrahim et al., 2021) before interventions began, medical interventions and vector control might have further reduced these levels, making a reinvasion and subsequent re-establishment of HAT very unlikely. Maro is close to the border of the Central African Republic, and the area has not been well investigated concerning refugee populations of tsetse, which could contribute to a reinvasion of the Maro zone. The higher level of genetic heterogeneity of the Maro population indicates that invasions from neighboring populations are already ongoing. This immigration could also be the reason for not detecting the bottleneck signature in the Maro population. The two HAT areas need different levels of attention while implementing vector eradication programs. While Madoul is relatively safe against reinvasion, Maro needs another type of attention, as frequent and persistent immigration might counteract eradication efforts. Thus, it is recommended that continuous tsetse suppression needs to be implemented in Maro. This study shows nicely that an in-depth knowledge of the processes within and between populations is needed to understand how these populations behave. This can be used to extrapolate, make predictions, and inform the organisations implementing vector control programs to include valuable adjustments, as in the case of Maro. Such integrative approaches can help prevent the failure of programs, potentially saving costs and preventing infections of humans and animals who might die if not treated. References Ibrahim MAM, Weber JS, Ngomtcho SCH, Signaboubo D, Berger P, Hassane HM, Kelm S (2021) Diversity of trypanosomes in humans and cattle in the HAT foci Mandoul and Maro, Southern Chad- Southern Chad-A matter of concern for zoonotic potential? PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 15, e000 323. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0009323 Ravel S, Mahamat MH, Ségard A, Argiles-Herrero R, Bouyer J, Rayaisse JB, Solano P, Mollo BG, Pèka M, Darnas J, Belem AMG, Yoni W, Noûs C, de Meeûs T (2023) Population genetics of Glossina fuscipes fuscipes from southern Chad. Zenodo, ver. 9 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7763870 WHO (2022) Trypanosomiasis, human African (sleeping sickness). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/trypanosomiasis-human-african-(sleeping-sickness), retrieved 17. March 2023 | Population genetics of Glossina fuscipes fuscipes from southern Chad | Sophie Ravel, Mahamat Hissène Mahamat, Adeline Ségard, Rafael Argiles-Herrero, Jérémy Bouyer, Jean-Baptiste Rayaisse, Philippe Solano, Brahim Guihini Mollo, Mallaye Pèka, Justin Darnas, Adrien Marie Gaston Belem, Wilfrid Yoni, Camille Noûs, Thierr... | <p>In Subsaharan Africa, tsetse flies (genus Glossina) are vectors of trypanosomes causing Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT) and Animal African Trypanosomosis (AAT). Some foci of HAT persist in Southern Chad, where a program of tsetse control wa... | Biology, Ecology, Evolution, Genetics/Genomics, Insecta, Medical entomology, Parasitology, Pest management, Veterinary entomology | Michael Lattorff | Audrey Bras | 2022-04-22 11:25:24 | View | |

09 Feb 2023

A novel nematode species from the Siberian permafrost shares adaptive mechanisms for cryptobiotic survival with C. elegans dauer larvaAnastasia Shatilovich, Vamshidhar R. Gade, Martin Pippel, Tarja T. Hoffmeyer, Alexei V. Tchesunov, Lewis Stevens, Sylke Winkler, Graham M. Hughes, Sofia Traikov, Michael Hiller, Elizaveta Rivkina, Philipp H. Schiffer, Eugene W Myers, Teymuras V. Kurzchalia https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.28.478251A novel nematode species from the Siberian permafrost shares adaptive mechanisms for cryptobiotic survival with C. elegans dauer larvaRecommended by Isa Schon based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThis article [1] investigated two nematode genera, Panagrolaimus and Plectus, from the Siberian permafrost to unravel the adaptations allowing them to survive cryptobiosis; radio carbon dating showed that the individuals of Panagrolaimus had been in cryobiosis in Siberia for as long as 46,000 years! I was impressed by the multidisciplinary approach of this study, including morphological as well as phylogenetic and -genomic analyses to describe a new species. In triploids as some of the species studied here, it is quite challenging to assemble a novel genome. The authors furthermore not only managed to successfully reanimate the Siberian specimens but could also expose them to repeated freezing and desiccation in the lab, not an easy task. This study reports some amazing discoveries - comparing the molecular toolkits between C. elegans and Panagrolaimus and Plectus revealed that several components were orthologues. Likewise, some of the biochemical mechanisms for surviving freezing in the lab turned out to be similar for C. elegans and the Siberian nematodes. This study thus provides strong evidence that nematodes developed specific mechanisms allowing them to stay in cryobiosis over very long times. A surprising additional experimental result concerns the well-studied C. elegans - dauer larvae of this species can stay viable much longer after periods of animated suspension than previously thought. I highly recommend this article as it is an important contribution to the fields of evolution and molecular biology. This study greatly advanced our understanding of how nematodes could have adapted to cryobiosis. The applied techniques could also be useful for studying similar research questions in other organisms. Reference [1] Shatilovich A, Gade VR, Pippel M, Hoffmeyer TT, Tchesunov AV, Stevens L, Winkler S, Hughes GM, Traikov S, Hiller M, Rivkina E, Schiffer PH, Myers EW, Kurzchalia TV (2023) A novel nematode species from the Siberian permafrost shares adaptive mechanisms for cryptobiotic survival with C. elegans dauer larva. bioRxiv, 2022.01.28.478251, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.28.478251 | A novel nematode species from the Siberian permafrost shares adaptive mechanisms for cryptobiotic survival with C. elegans dauer larva | Anastasia Shatilovich, Vamshidhar R. Gade, Martin Pippel, Tarja T. Hoffmeyer, Alexei V. Tchesunov, Lewis Stevens, Sylke Winkler, Graham M. Hughes, Sofia Traikov, Michael Hiller, Elizaveta Rivkina, Philipp H. Schiffer, Eugene W Myers, Teymuras V. K... | <p style="text-align: justify;">Some organisms in nature have developed the ability to enter a state of suspended metabolism called cryptobiosis1 when environmental conditions are unfavorable. This state-transition requires the execution of comple... |  | Ecology, Evolution, Genetics/Genomics | Isa Schon | 2022-05-20 14:32:02 | View | |

20 Dec 2022

Non-target effects of ten essential oils on the egg parasitoid Trichogramma evanescensLouise van Oudenhove, Aurélie Cazier, Marine Fillaud, Anne-Violette Lavoir, Hicham Fatnassi, Guy Pérez, Vincent Calcagno https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.14.476310Side effects of essential oils on pest natural enemiesRecommended by Cedric Pennetier based on reviews by Olivier Roux and 2 anonymous reviewersIntegrated pest management relies on the combined use of different practices in time and/or space. The main objectives are to better control pests, not to induce too much selective pressure on resistance mechanisms present in pest populations and to minimize non-targeted effects on the ecosystem [1]. The efficiency of such a strategy requires at least additional or synergistic effects of chosen tools against targeted pest population in a specific environment. Any antagonistic effect on targeted or non-targeted organisms might reduce control effort to nil even worst. Van Oudenhove et al [2] raised the question of the interaction between botanical pesticides (BPs) and egg parasitoids. Each of these two strategies used for pest management present advantages and are described as eco-friendly. First, the use of parasitoids is a great example of biological control and is massively used in a broad range of crop production in different ecological settings. Second, BPs, especially essential oils (EOs) used for a wide range of activities on pests (repellent, antifeedant, antiovipositant, ovicidal, larvicidal and simply pesticidal) present low-toxicity to non-target vertebrates and do not last too long in the environment. Combining these two strategies might be considered as a great opportunity to better pest control with minimized impact on environment. However, EOs used to target a wide range of pest might directly or indirectly affect parasitoids. Van Oudenhove et al [2] focused their study on non-target effects of 10 essentials oils with pesticide potential on larval development and egg-seeking behaviour of five strains of the biocontrol agent Trichogramma evanescens. Within two laboratory experiments mimicing EOs fumigation (i.e. contactless EOs exposure), the authors evaluated (1) the toxicity of EOs on parasitoid development and (2) the repellent effect of these EOs on adult wasps. They confirmed that contactless exposure of EOs can (1) induce mortality during pre-imaginal development (more acute at the pupal stage) and (2) induce behavioural avoidance of EOs odour plume. These experiments ran onto five strains of T. evanescens also highlighted the variation of the effects of EOs among parasitoid strains. The complex and dynamic interaction between pest, plant, parasitoid (a natural enemy) and their environment is disturbed by EOs. EOs plumes are also dynamic and variable upon the environmental conditions. The results of van Oudenhove et al. experimentally illustrate such a complexity by describing opposite effects (repellent and attractive) of the same EO on the behaviour of two T. evanescens strains. These contrasting results led us to question more broadly the non-target effects of pest management programs based on EOs fumigation on natural enemies. Finally, the limits of this experimental study as discussed in the paper draw research avenues taking into account biotic variables such as plant chemical cues, odour plume dynamics, individual behavioural experiences and abiotic variables such as temperature, light and gravity [3] in laboratory, semi-field and field experiments. Facing such a complexity, modelling studies at fine scale in time and space have the operational objective to help farmers to choose the best IPM strategy regarding their environment (as illustrated for aphid population management in the recent review by Stell et al. [4]). But before such research effort to be undertaken, Van Oudenhove et al study [2] sounds like an alert for a cautious use of EOs in pest control programs that integrate biological control with parasitoids.

References [1] Fauvergue, X. Biocontrôle Elements Pour Une Protection Agroecologique des Cultures; Éditions Quae: Versailles, France, 2020. [2] van Oudenhove L, Cazier A, Fillaud M, Lavoir AV, Fatnassi H, Pérez G, Calcagno V. Non-target effects of ten essential oils on the egg parasitoid Trichogramma evanescens. bioRxiv 2022.01.14.476310, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.14.476310 [3] Victor Burte, Guy Perez, Faten Ayed, Géraldine Groussier, Ludovic Mailleret, Louise van Oudenhove and Vincent Calcagno (2022) Up and to the light: intra- and interspecific variability of photo- and geo-tactic oviposition preferences in genus Trichogramma, Peer Community Journal, 2: e3. https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.78 [4] Stell E, Meiss H, Lasserre-Joulin F, Therond O. Towards Predictions of Interaction Dynamics between Cereal Aphids and Their Natural Enemies: A Review. Insects 2022, 13, 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13050479 | Non-target effects of ten essential oils on the egg parasitoid Trichogramma evanescens | Louise van Oudenhove, Aurélie Cazier, Marine Fillaud, Anne-Violette Lavoir, Hicham Fatnassi, Guy Pérez, Vincent Calcagno | <p style="text-align: justify;">Essential oils (EOs) are increasingly used as biopesticides due to their insecticidal potential. This study addresses their non-target effects on a biological control agent: the egg parasitoid <em>Trichogramma evane... |  | Behavior, Biochemistry, Biocontrol, Biodiversity, Computer modelling, Conservation biology, Demography/population dynamics, Development, Ecology, Insecta, Insectivores, Invertebrates, Life histories, Methodology, Pest management, Theoretical biolo... | Cedric Pennetier | 2022-01-31 16:05:32 | View | |

30 Nov 2022

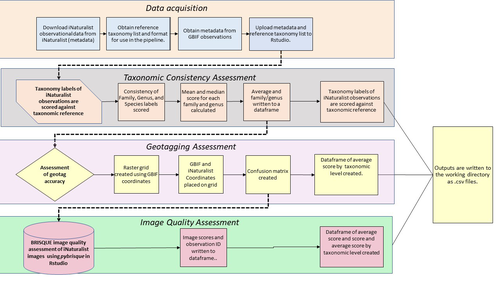

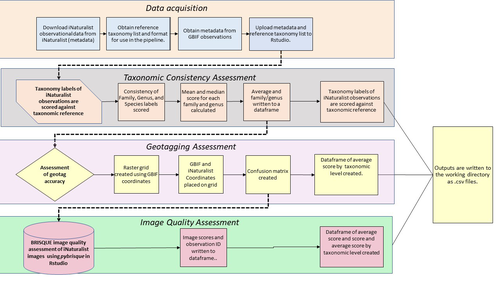

A pipeline for assessing the quality of images and metadata from crowd-sourced databases.Jackie Billotte https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.29.490112Harnessing the full potential of iNaturalist and other databasesRecommended by Matthias Foellmer based on reviews by Clive Hambler and Catherine ScottThe popularity of iNaturalist and other online biodiversity databases to which the general public and specialists alike contribute observations has skyrocketed in recent years (Dance 2022). The AI-based algorithms (computer vision) which provide the first identification of a given organism on an uploaded photograph have become very sophisticated, suggesting initial identifications often down to species level with a surprisingly high degree of accuracy. The initial identifications are then confirmed or improved by feedback from the community, which works particularly well for organismal groups to which many active community members contribute, such as the birds. Hence, providing initial observations and identifying observations of others, as well as browsing the recorded biodiversity for given locales or the range of occurrences of individual taxa has become a meaningful and satisfying experience for the interested naturalist. Furthermore, several research studies have now been published relying on observations uploaded to iNaturalist (Szentivanyi and Vincze 2022). However, using the enormous amount of natural history data available on iNaturalist in a systematic way has remained challenging, since this requires not only retrieving numerous observations from the database (in the hundreds or even thousands), but also some level of transparent quality control. Billotte (2022) provides a protocol and R scripts for the quality assessment of downloaded observations from iNaturalist, allowing an efficient and reproducible stepwise approach to prepare a high-quality data set for further analysis. First, observations with their associated metadata are downloaded from iNaturalist, along with the corresponding entries from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). In addition, a taxonomic reference list is obtained (these are available online for many taxa), which is used to assess the taxonomic consistency in the dataset. Second, the geo-tagging is assessed by comparing the iNaturalist and GBIF metadata. Lastly, the image quality is assessed using pyBRISQUE. The approach is illustrated using spiders (Araneae) as an example. Spiders are a very diverse taxon and an excellent taxonomic reference list is available (World Spider Catalogue 2022). However, spiders are not well known to most non-specialists, and it is not easy to take good pictures of spiders without using professional equipment. Therefore, the ability of iNaturalist’s computer vision to provide identifications is limited to this date and the community of specialists active on iNaturalist is comparatively small. Hence, spiders are a good taxon to demonstrate how the pipeline results in a quality-controlled dataset based on crowed-sourced data. Importantly, the software employed is free to use, although inevitably, the initial learning curve to use R scripts can be steep, depending on prior expertise with R/RStudio. Furthermore, the approach is employable with databases other than iNaturalist. In summary, Billotte's (2022) pipeline allows researchers to use the wealth of observations on iNaturalist and other databases to produce large metadata and image datasets of high-quality in a reproducible way. This should pave the way for more studies, which could include, for example, the assessment of range expansions of invasive species or the evaluation of the presence of endangered species, potentially supporting conservation efforts. References Billotte J (2022) A pipeline for assessing the quality of images and metadata from crowd-sourced databases. BiorXiv, 2022.04.29.490112, ver 5 peer reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.29.490112 Dance A (2022) Community science draws on the power of the crowd. Nature, 609, 641–643. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-02921-3 Szentivanyi T, Vincze O (2022) Tracking wildlife diseases using community science: an example through toad myiasis. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 68, 74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-022-01623-5 World Spider Catalog (2022). World Spider Catalog. Version 23.5. Natural History Museum Bern, online at http://wsc.nmbe.ch. https://doi.org/10.24436/2 | A pipeline for assessing the quality of images and metadata from crowd-sourced databases. | Jackie Billotte | <p style="text-align: justify;">Crowd-sourced biodiversity databases provide easy access to data and images for ecological education and research. One concern with using publicly sourced databases; however, is the quality of their images, taxonomi... |  | Arachnids, Biodiversity, Biology, Conservation biology, Ecology, Insecta, Invertebrates | Matthias Foellmer | 2022-05-03 00:18:23 | View | |

28 Aug 2022

A simple procedure to detect, test for the presence of stuttering, and cure stuttered data with spreadsheet programsThierry de Meeûs and Camille Noûs https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7029324Improved population genetics parameters through control for microsatellite stutteringRecommended by Michael Lattorff based on reviews by Thibaut Malausa, Fabien Halkett and Thierry Rigaud based on reviews by Thibaut Malausa, Fabien Halkett and Thierry Rigaud

Molecular markers have drastically changed and improved our understanding of biological processes. In combination with PCR, markers revolutionized the study of all organisms, even tiny insects, and eukaryotic pathogens amongst others. Microsatellite markers were the most prominent and successful ones. Their success started in the early 1990s. They were used for population genetic studies, mapping of genes and genomes, and paternity testing and inference of relatedness. Their popularity is based on some of their characteristics as codominance, the high polymorphism information content, and their ease of isolation (Schlötterer 2004). Still, microsatellites are the marker of choice for a range of non-model organisms as next-generation sequencing technologies produce a huge amount of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), but often at expense of sample size and higher costs. | A simple procedure to detect, test for the presence of stuttering, and cure stuttered data with spreadsheet programs | Thierry de Meeûs and Camille Noûs | <p>Microsatellite are powerful markers for empirical population genetics, but may be affected by amplification problems like stuttering that produces heterozygote deficits between alleles with one repeat difference. In this paper, we present a sim... | Acari, Ecology, Evolution, Genetics/Genomics, Helminthology, Invertebrates, Medical entomology, Molecular biology, Parasitology, Theoretical biology, Veterinary entomology | Michael Lattorff | 2021-12-06 14:30:47 | View | ||

26 Aug 2022

Within and among population differences in cuticular hydrocarbons in the seabird tick Ixodes uriaeMarlène Dupraz, Chloe Leroy, Thorkell Lindberg Thórarinsson, Patrizia d’Ettorre, Karen D. McCoy https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.21.477272Seabird tick diversification and cuticular hydrocarbonsRecommended by Felix Sperling based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersTicks are notorious vectors of diseases in humans and other vertebrates. Much effort has been expended to understand tick diversity and ecology with the aim of managing their populations to alleviate the misery they bring. Further, the fundamental question of whether ticks are usually host generalists or host specialists has been debated at length and is important both for understanding the mechanisms of their diversification as well as for focusing control of ticks [1]. One elegant resolution of this question is to consider most tick species to be global generalists but local specialists [1]. This is well illustrated in a series of studies of the seabird tick, Ixodes uriae, which is comprised of host-specific races that show genetic [2], morphological [3] and host performance [4] differences associated with the seabirds they feed on. Such a pattern has clear ramifications for sympatric speciation; however, the factors that potentially act to drive these differences have remained elusive. Dupraz et al. [5] have now made intriguing and important steps toward bridging the gap between demonstrating local patterns of tick host association and understanding the physiological mechanisms that may facilitate such divergences. They collected I. uriae ticks from the nests of two seabirds – Atlantic puffins and common guillemots – on the north side of Iceland. Four populations of ticks were sampled, with one island providing both puffin ticks and guillemot ticks, to give two tick populations from each of the two seabird host species. They then washed the ticks in solvent and analyzed the dissolved cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs) using GC mass spectrometry, revealing 22 different hydrocarbon compounds common to most of these samples. CHCs are known to be important across arthropods for a variety of functions ranging from reducing water loss to facilitating communication and recognition between individuals with species. Dupraz et al. [5] found three hydrocarbons that distinguished puffin ticks most consistently from guillemot ticks. A cross-validation test for host type also assigned 75% of the tick pools to the seabird host of origin. However, with these limited sample sizes, statistical analysis revealed no significant difference in CHC profiles between the host types, although a tendency was evident. Nonetheless, this study revealed a number of potentially diagnostic CHCs for tick host type, as well as some that may be more diagnostic of locations. This provides a fascinating and actionable foundation for further work using additional sites and host types, as well as an entry point into discerning the mechanisms at play in producing the diversity, complexity and adaptability that make ticks such medical menaces. References | Within and among population differences in cuticular hydrocarbons in the seabird tick Ixodes uriae | Marlène Dupraz, Chloe Leroy, Thorkell Lindberg Thórarinsson, Patrizia d’Ettorre, Karen D. McCoy | <p>The hydrophobic layer of the arthropod cuticle acts to maintain water balance, but can also serve to transmit chemical signals via cuticular hydrocarbons (CHC), essential mediators of arthropod behavior. CHC signatures typically vary qualitativ... |  | Acari, Biology, Ecology, Evolution | Felix Sperling | 2022-02-08 13:00:52 | View | |

25 Aug 2022

Improving species conservation plans under IUCN's One Plan Approach using quantitative genetic methodsDrew Sauve, Jane Hudecki, Jessica Steiner, Hazel Wheeler, Colleen Lynch, Amy A. Chabot https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/n3zxpQuantitative genetics for a more qualitative conservationRecommended by Peter Galbusera based on reviews by Timothée Bonnet and 1 anonymous reviewerGenetic (bio)diversity is one of three recognised levels of biodiversity, besides species and ecosystem diversity. Its importance for species survival and adaptation is increasingly highlighted and its monitoring recommended (e.g. O’Brien et al 2022). Especially the management of ex-situ populations has a long history of taking into account genetic aspects (through pedigree analysis but increasingly also by applying molecular tools). As in-situ and ex-situ efforts are nowadays often aligned (in a One-Plan-Approach), genetic management is becoming more the standard (supported by quickly developing genomic techniques). However, rarely quantitative genetic aspects are raised in this issue, while its relevance cannot be underestimated. Hence, the current manuscript by Sauve et al (2022) is a welcome contribution, in order to improve conservation efforts. The authors give a clear overview on how quantitative genetic analysis can aid the measurement, monitoring, prediction and management of adaptive genetic variation. The main tools are pedigrees (mainly of ex-situ populations) and the Animal Model. The main goal is to prevent adaption to captivity and altered genetics in general (in reintroduction projects). The confounding factors to take into account (like inbreeding, population structure, differences between facilities, sample size and parental/social effects) are well described by the authors. As such, I fully recommend this manuscript for publication, hoping increased interest in quantitative analysis will benefit the quality of species conservation management. References O'Brien D, Laikre L, Hoban S, Bruford MW et al. (2022) Bringing together approaches to reporting on within species genetic diversity. Journal of Applied Ecology, 00, 1–7. https://doi/10.1111/1365-2664.14225 Sauve D., Spero J., Steiner J., Wheeler H., Lynch C., Chabot A.A. (2022) Improving species conservation plans under IUCN’s One Plan Approach using quantitative genetic methods. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 9 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/n3zxp | Improving species conservation plans under IUCN's One Plan Approach using quantitative genetic methods | Drew Sauve, Jane Hudecki, Jessica Steiner, Hazel Wheeler, Colleen Lynch, Amy A. Chabot | <p>Human activities are resulting in altered environmental conditions that are impacting the demography and evolution of species globally. If we wish to prevent anthropogenic extinction and extirpation, we need to improve our ability to restore wi... |  | Conservation biology, Ecology, Evolution, Genetics/Genomics | Peter Galbusera | 2022-02-21 10:45:22 | View |