Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * ▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

02 Nov 2021

Cuckoo male bumblebees perform slower and longer flower visits than free-living male and worker bumblebeesAlessandro Fisogni, Gherardo Bogo, François Massol, Laura Bortolotti, Marta Galloni https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4489066Cuckoo bumblebee males might reduce plant fitnessRecommended by Michael Lattorff based on reviews by Patrick Lhomme, Silvio Erler and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Patrick Lhomme, Silvio Erler and 2 anonymous reviewers

In pollinator insects, especially bees, foraging is almost exclusively performed by females due to the close linkage with brood care. They collect pollen as a protein- and lipid-rich food to feed developing larvae in solitary and social species. Bees take carbohydrate-rich nectar in small quantities to fuel their flight and carry the pollen load. To optimise the foraging flight, they tend to be flower constant, reducing the flower handling time and time among individual inflorescences (Goulson, 1999). Males of pollinator species might be found on flowers as well. As they do not collect any pollen for brood care, their foraging flights and visits to flowers might not be shaped by the selective forces that optimise the foraging flights of females. They might stay longer in individual flowers, take up nectar if needed, but might unintentionally carry pollen on their body surface (Wolf & Moritz, 2014). | Cuckoo male bumblebees perform slower and longer flower visits than free-living male and worker bumblebees | Alessandro Fisogni, Gherardo Bogo, François Massol, Laura Bortolotti, Marta Galloni | <p>Cuckoo bumblebees are a monophyletic group within the genus Bombus and social parasites of free-living bumblebees, upon which they rely to rear their offspring. Cuckoo bumblebees lack the worker caste and visit flowers primarily for their own s... |  | Behavior, Biology, Ecology, Insecta, Invertebrates, Terrestrial | Michael Lattorff | Patrick Lhomme, Seth Barribeau , Silvio Erler, Denis Michez | 2021-02-02 01:41:35 | View |

05 Jan 2021

Do substrate roughness and gap distance impact gap-bridging strategies in arboreal chameleons?Allison M. Luger, Vincent Vermeylen, Anthony Herrel, Dominique Adriaens https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.260596Gap-bridging strategies in arboreal chameleonsRecommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Simon Baeckens and 2 anonymous reviewersUntil now, very little is known about the tail use and functional performance in tail prehensile animals. Luger et al. (2020) are the first to provide explorative observations on trait related modulation of tail use, despite the lack of a sufficiently standardized data set to allow statistical testing. They described whether gap distance, perch diameter, and perch roughness influence tail use and overall locomotor behavior of the species Chamaeleo calyptratus. References Luger, A.M., Vermeylen, V., Herrel, A. and Adriaens, D. (2020) Do substrate roughness and gap distance impact gap-bridging strategies in arboreal chameleons? bioRxiv, 2020.08.21.260596, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.260596 | Do substrate roughness and gap distance impact gap-bridging strategies in arboreal chameleons? | Allison M. Luger, Vincent Vermeylen, Anthony Herrel, Dominique Adriaens | <p>Chameleons are well-equipped for an arboreal lifestyle, having ‘zygodactylous’ hands and feet as well as a fully prehensile tail. However, to what degree tail use is preferred over autopod prehension has been largely neglected. Using an indoor ... |  | Behavior, Biology, Herpetology, Reptiles, Vertebrates | Ellen Decaestecker | 2020-08-25 10:06:42 | View | |

25 Mar 2022

Pre- and post-oviposition behavioural strategies to protect eggs against extreme winter cold in an insect with maternal careJean-Claude Tourneur, Claire Cole, Jess Vickruck, Simon Dupont, Joel Meunier https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.23.469705New insights into maternal egg care in insects: egg transport as an adaptive behavior to extreme temperatures in the European earwigRecommended by Anna Cohuet based on reviews by Ana Rivero, Nicolas Sauvion and Wolf U. BlanckenhornBecause of the inability of eggs to move, the fitness of oviparous organisms is particularly dependent on the oviposition site. The choice of oviposition site by mothers is therefore the result of trade-offs between exposure to risk factors or favorable conditions such as the presence/absence of predators, the threat of extreme temperatures, the risk of desiccation, the presence and quality of nutritional resources... In addition to these trade-offs between different biotic and abiotic factors that determine oviposition site selection, the ability of mothers to move their eggs after oviposition is a game-changer in insect strategies to optimize egg development and survival [1]. Oviposition site selection combined with egg transport has been explored in insects in relation to the risk of exposure to egg parasitoids [2] or needs for oxygenation [3] but surprisingly has not been investigated in regards to temperatures. Considering egg transport in the ability of insects to adapt their behavior to environmental conditions and in particular to potential extreme temperatures is yet inherent in providing a complete picture of the diversity of behaviors that shape adaptation to temperature and potential tolerance to climate change. In this sense, the study presented by Tourneur et al. [4], explores whether insects capable of egg-care might use egg transport as an adaptive behavior to protect them from suboptimal or extreme temperatures. The study was conducted in the European earwig, Forficula auricularia Linnaeus, 1758, which is known to practice egg-care in a variety of ways, that presumably includes egg-transportation, for several weeks or months during winter until hatching. The authors characterized different life-history traits related to egg-laying, egg-transport, and egg-development in two device systems with three experimental temperature regimes in two populations of European earwigs from Canada. The inclusion of two populations, which turned out to belong to two clades, allowed the identification of a diversity of behaviors although this did not allow to attribute the differences between the two populations to specific population differences, genetic differences, or to their geographical origins. Interestingly, the study showed that oviposition site selection in the European earwig is driven by temperature and that in winter temperatures, female earwigs may move their eggs to warmer temperatures that are adequate for hatching. These results are original in the sense that they highlight new adaptive strategies in female insects used during the post-oviposition stage to protect their eggs from temperature changes. In the current context of climate change and potential changes in selective pressures, the study contributes to the understanding of the wide range of strategies deployed by insects to adapt to the temperature. This appears essential to predict and anticipate the consequences of global instability, it also describes from an academic point of view a new and fascinating adaptive strategy in an overlooked biological system. References [1] Machado G, Trumbo ST (2018) Parental care. In: Insect Behavior, pp. 203–218. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198797500.003.0014 [2] Carrasco D, Kaitala A (2009) Egg-laying tactic in Phyllomorpha laciniata in the presence of parasitoids. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 131, 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2009.00857.x [3] Smith RL (1997) Evolution of paternal care in the giant water bugs (Heteroptera: Belostomatidae). In: The Evolution of Social Behaviour in Insects and Arachnids (eds Crespi BJ, Choe JC), pp. 116–149. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511721953.007 [4] Tourneur J-C, Cole C, Vickruck J, Dupont S, Meunier J (2022) Pre- and post-oviposition behavioural strategies to protect eggs against extreme winter cold in an insect with maternal care. bioRxiv, 2021.11.23.469705, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.23.469705 | Pre- and post-oviposition behavioural strategies to protect eggs against extreme winter cold in an insect with maternal care | Jean-Claude Tourneur, Claire Cole, Jess Vickruck, Simon Dupont, Joel Meunier | <p style="text-align: justify;">Depositing eggs in an area with adequate temperature is often crucial for mothers and their offspring, as the eggs are immobile and therefore cannot avoid exposure to sub-optimal temperatures. However, the importanc... |  | Behavior, Ecology, Evolution, Insecta, Invertebrates, Life histories | Anna Cohuet | 2021-11-24 16:43:06 | View | |

01 Jul 2020

Sub-lethal insecticide exposure affects host biting efficiency of Kdr-resistant Anopheles gambiaeMalal Mamadou Diop, Fabrice Chandre, Marie Rossignol, Angelique Porciani, Mathieu Chateau, Nicolas Moiroux, Cedric Pennetier https://doi.org/10.1101/653980kdr homozygous resistant An. gambiae displayed enhanced feeding success when exposed to permethrin Insect-Treated NetsRecommended by Adrian Diaz based on reviews by Thomas Guillemaud, Niels Verhulst, Etienne Bilgo and 1 anonymous reviewerMalaria is a vector-borne parasitic disease found in 91 countries with an estimated of 228 million cases occurred worldwide during 2018. The 93% (213 million) of those cases were reported in the African Region (WHO 2019). Six species of Plasmodium parasites can produce the disease but only P. falciparum and P. vivax are the predominant species globally. More than 40 species of Anopheles mosquitoes are important malaria vectors (Asley et al. 2018). Intrinsic (genetic background, parasite susceptibility) and extrinsic (feeding host preference, host diversity and availability, mosquito abundance) factors affect the capacity of mosquitoes to vector the disease (Macdonald 1952). Malaria is prevented by chemoprophylaxis, vaccination, bite-avoidance and vector-control measures. The mainstays of vector control are long-lasting insecticide (pyrethroid) treated nets and indoor residual spraying with insecticides (Asley et al. 2018). The widespread use of pyrethroid insecticides forced the emergence of insecticide resistance in malaria vectors reducing the insecticidal effect. Mosquitoes can modify their behaviour avoiding insecticide contact and so potentially reducing vector control tools efficacy. In this sense, Diop et al. (2020) investigated whether pre-exposure to an Insecticide-Treated Net (ITN) modulates the mosquito ability to take a blood meal in Anopheles gambiae. By means of video recording experiments the authors analyzed how the feeding/bitting behaviour was affected by kdr mutation genotypes (homozygous susceptible – SS-, heterozygotes -RS- and homozygous resistant -RR-) when exposed to two different insecticides (permethrin and deltamethrin). According to the results, the blood-feeding success did not differ between the three genotypes in the absence of insecticide exposure. However, authors observed differences in the feeding duration and blood meal size. In example, RR mosquitoes spent less time taking their blood meal than RS and SS. On the other hand, RS mosquitoes took higher blood volumes than RR females. These differences can affect the mosquito fitness by decreasing/increasing the likelihood to be killed by the host defensive behavior or increase the oogenesis so enhancing fecundity. Regarding the effect of exposition to insecticides authors detected a strong relationship between kdr genotype and Knock Down (KD) phenotype when mosquitoes were exposed to Permethrin. Previously, the authors have evidenced that RR mosquitoes prefer a host protected by a permethrin-treated net rather than an untreated net and that heterozygotes RS mosquitoes have a remarkable ability to find a hole into a bet net (Diop et al. 2015, Porciani et al. 2017). With data here obtained, they demonstrated that kdr homozygous resistant An. gambiae displayed enhanced feeding success when exposed to permethrin ITN. The changes observed in the feeding/biting mosquito behaviour can affect their fitness shaping the evolution of the insecticide resistance in mosquitoes’ natural populations. Moreover, this may also alter parasite transmission dynamics by modifying vector/host interactions and so vector capacity. References World Health Organization (2019). World malaria report 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. ISBN 978-92-4-156572-1 | Sub-lethal insecticide exposure affects host biting efficiency of Kdr-resistant Anopheles gambiae | Malal Mamadou Diop, Fabrice Chandre, Marie Rossignol, Angelique Porciani, Mathieu Chateau, Nicolas Moiroux, Cedric Pennetier | <p>The massive use of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) has drastically changed the environment for malaria vector mosquitoes, challenging their host-seeking behaviour and biting success. Here, we investigated the effect of a brief exposure to an IT... |  | Behavior, Ecology, Evolution, Medical entomology, Pesticide resistance | Adrian Diaz | Anonymous | 2019-05-29 19:40:25 | View |

07 Jun 2024

Relationship between weapon size and six key behavioural and physiological traits in males of the European earwigSamantha E.M. Blackwell, Laura Pasquier, Simon Dupont, Séverine Devers, Charlotte Lécureuil, *Joël Meunier https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.20.585871The unreliable signal: No correlation between forceps length and male quality in European earwigsRecommended by Olivier Roux based on reviews by Luna Grey and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Luna Grey and 2 anonymous reviewers

In animals, male weapons such as antlers, horns, spurs, fangs, and tusks typically provide advantages in male contests and increase access to females, thereby enhancing reproductive success. However, such large and extravagant morphological structures are expected to come at a cost, potentially imposing trade-offs with life history traits, physiological functions, or certain behaviors (Emlen, 2001; Emlen, 2008). These costs should be manageable only by males in the best condition. The present study by Blackwell et al. (2024) examines this assumption through a comprehensive study on the European earwig, where males possess forceps-like cerci that vary widely in size within populations. In the European earwig (Forficula auricularia), male forceps are used in male-male contests as weapons to deter competitors prior to mating (Styrsky & Rhein, 1999) or to interrupt mating pairs by non-copulating males (Forslund, 2000; Walker & Fell, 2001). Despite providing benefits in terms of mating success (Eberhard & Gutierrez, 1991; Tomkins & Brown, 2004), it remains unknown whether long or short forceps are associated with other important life-history traits. In this laboratory study, Blackwell et al. (2024) investigated two European earwig populations, each divided into two subpopulations: one with the shortest forceps and one with the longest forceps. They examined the potential costs of long forceps on six different traits: one reproductive trait (sperm storage); three non-reproductive behavioral traits such as locomotor performance (involved in search for resources), fleeing reaction face to a risk (long forceps are supposed to be correlated with boldness), and aggregation behavior (European earwigs are facultative group-living organisms); and survival (when deprived of food and subsequently when exposed to an entomopathogenic fungus). As males in the best condition are supposed to be those that can afford to develop large forceps, Blackwell et al. (2024) predicted that males with long forceps would perform better than those with short forceps across the investigated traits. However, their predictions were not validated, as no correlation between weapon size and male quality was detected in either population. Although the sample size is sometimes limited, the consistency of these results across different populations adds robustness to their conclusions. By demonstrating that forceps length in the European earwig does not reliably indicate male quality, this paper challenges existing theories and highlights the complexity of evolutionary processes shaping morphological traits. Furthermore, the study raises important questions about the evolutionary mechanisms maintaining weapon size diversity, providing a fresh perspective that could stimulate further research and debate in the field, notably the search for other traits where costs might be incurred. References Blackwell, S.E.M., Pasquier, L., Dupont, S., Devers, S., Lécureuil, C. & Meunier, J. (2024). Relationship between weapon size and six key behavioural and physiological traits in males of the European earwig. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.20.585871 Eberhard, W.G., & Gutierrez, E.E. (1991). Male dimorphisms in beetles and earwigs and the question of developmental constraints. Evolution, 45(1), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/2409478 Emlen, D.J. (2001). Costs and the diversification of exaggerated animal structures. Science, 291(5508), 1534–1536. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1056607 Emlen, D.J. (2008). The evolution of animal weapons. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 39(1), 387–413. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173502 Forslund, P. (2000). Male-male competition and large size mating advantage in European earwigs, Forficula auricularia. Animal Behaviour, 59(4), 753–762. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.1999.1359 Styrsky, J.D., & Rhein, S.V. (1999). Forceps size does not determine fighting success in European earwigs. Journal of Insect Behavior, 12(4), 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020962606724 Tomkins, J.L., & Brown, G.S. (2004). Population density drives the local evolution of a threshold dimorphism. Nature, 431, 1099–1103. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02936.1. Walker, K.A., & Fell, R.D. (2001). Courtship roles of male and female European earwigs, Forficula auricularia L. (Dermaptera: Forficulidae), and sexual use of forceps. Journal of Insect Behavior, 14(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007843227591 | Relationship between weapon size and six key behavioural and physiological traits in males of the European earwig | Samantha E.M. Blackwell, Laura Pasquier, Simon Dupont, Séverine Devers, Charlotte Lécureuil, *Joël Meunier | <p style="text-align: justify;">In many animals, male weapons are large and extravagant morphological structures that typically enhance fighting ability and reproductive success. It is generally assumed that growing and carrying large weapons is c... |  | Behavior, Evolution, Insecta, Invertebrates, Life histories, Morphology | Olivier Roux | 2024-03-26 08:56:27 | View | |

22 Jul 2020

The open bar is closed: restructuration of a native parasitoid community following successful control of an invasive pest.David Muru, Nicolas Borowiec, Marcel Thaon, Nicolas Ris, Madalina Ionela Viciriuc, Sylvie Warot, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.20.884908Raise and fall of an invasive pest and consequences for native parasitoid communitiesRecommended by Stefaniya Kamenova based on reviews by Kévin Tougeron and Miguel González Ximénez de EmbúnHost-parasitoid interactions have been the focus of extensive ecological research for decades. One the of the major reasons is the importance host-parasitoid interactions play for the biological control of crop pests. Parasitoids are the main natural regulators for a large number of economically important pest insects, and in many cases they could be the only viable crop protection strategy. Parasitoids are also integral part of complex food webs whose structure and diversity display large spatio-temporal variations [1-3]. With the increasing globalization of human activities, the generalized spread and establishment of invasive species is a major cause of disruption in local community and food web spatio-temporal dynamics. In particular, the deliberate introduction of non-native parasitoids as part of biological control programs, aiming the suppression of established, and also highly invasive crop pests, is a common practice with potentially significant, yet poorly understood effects on local food web dynamics (e.g. [4]). References [1] Eveleigh ES, McCann KS, McCarthy PC, Pollock SJ, Lucarotti CJ, Morin B, McDougall GA, Strongman DB, Huber JT, Umbanhowar J, Faria LDB (2007). Fluctuations in density of an outbreak species drive diversity cascades in food webs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 16976-16981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704301104 | The open bar is closed: restructuration of a native parasitoid community following successful control of an invasive pest. | David Muru, Nicolas Borowiec, Marcel Thaon, Nicolas Ris, Madalina Ionela Viciriuc, Sylvie Warot, Elodie Vercken | <p>The rise of the Asian chestnut gall wasp *Dryocosmus kuriphilus* in France has benefited the native community of parasitoids originally associated with oak gall wasps by becoming an additional trophic subsidy and therefore perturbing population... |  | Biocontrol, Biological invasions, Ecology, Insecta | Stefaniya Kamenova | 2019-12-31 09:08:49 | View | |

08 Mar 2024

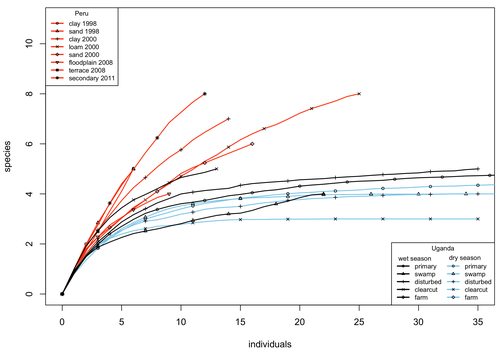

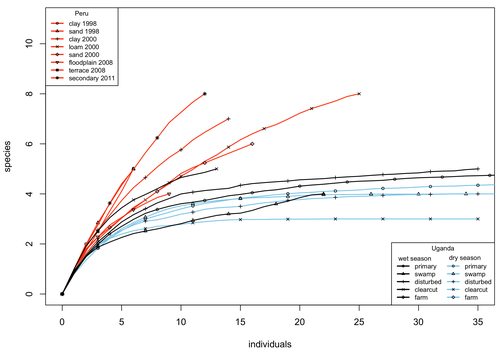

A comparison of the parasitoid wasp species richness of tropical forest sites in Peru and Uganda – subfamily Rhyssinae (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae)Tapani Hopkins, Hanna Tuomisto, Isrrael C. Gómez, Ilari E. Sääksjärvi https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.23.554460Two sides of tropical richness, parasitoid wasps collected by Malaise traps in tropical rainforests of South America and AfricaRecommended by Giovanny Fagua based on reviews by Mabel Alvarado, Filippo Di Giovanni and 2 anonymous reviewersInsect species richness and diversity comparisons between samples of the tropics around the world are rare, especially in taxa composed mainly of cryptic species as parasitoid wasps. The article by Hopkins et al. (2024) compares samples of parasitoid wasps of the subfamily Rhyssinae (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae) collected by Malaise traps in tropical rainforests of Perú and Uganda. The samples presented several differences in the time of collecting, covertures, and the sampling number; however, they used the same kind of traps, and the taxonomic process for species delimitation was made for the same team of ichneumonid experts, using equivalent characters. Publications about this kind of comparative study are difficult to find because cooperative projects on insect richness and diversity from South American and African continents are not frequent. In this sense, this study presented a valuable contrast that shows interesting results about the higher richness and lower abundance of the biota of the American tropics, even with a small sample, in comparison with the biota of the African tropics. The results are supported mainly by the rarefaction curves shown. This pattern of higher species richness and lower specimen abundance, observed in other American tropical taxa such as trees, birds, or butterflies, is observed too in these parasitoid wasps, increasing the body of information that could support the extension of the pattern to the entire biota of the American tropics. The authors recognize the study's limitations, which include strong differences in the size of the forest coverture between places. However, these differences and others are enough described and discussed. This work is useful because it increases the information about the diversity patterns of the tropics around the world and because study a taxon mainly composed of cryptic species, with a small amount of information in tropical regions. References Hopkins T., Tuomisto H., Gómez I.C., Sääksjärvi I. E. 2024. A comparison of the parasitoid wasp species richness of tropical forest sites in Peru and Uganda – subfamily Rhyssinae (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae). bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.23.554460 | A comparison of the parasitoid wasp species richness of tropical forest sites in Peru and Uganda – subfamily Rhyssinae (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae) | Tapani Hopkins, Hanna Tuomisto, Isrrael C. Gómez, Ilari E. Sääksjärvi | <p style="text-align: justify;">The global distribution of parasitoid wasp species richness is poorly known. Past attempts to compare data from different sites have been hampered by small sample sizes and lack of standardisation. During the past d... |  | Biodiversity, Biogeography, Insecta | Giovanny Fagua | 2023-08-24 18:30:26 | View | |

28 Apr 2021

Inference of the worldwide invasion routes of the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus using approximate Bayesian computation analysisSophie Mallez, Chantal Castagnone, Eric Lombaert, Philippe Castagnone-Sereno, Thomas Guillemaud https://doi.org/10.1101/452326Extracting the maximum historical information on pine wood nematode worldwide invasion from genetic dataRecommended by Stéphane Dupas based on reviews by Aude Gilabert and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Aude Gilabert and 1 anonymous reviewer

Redistribution of domesticated and non domesticated species by humans profoundly affected earth biogeography and in return human activities. This process accelerated exponentially since human expansion out of Africa, leading to the modern global, highly connected and homogenized, agriculture and trade system (Mack et al. 2000, Jaksic and Castro 2021), that threatens biological diversity and genetic resources. To accompany quarantine and control effort, the reconstruction of invasion routes provides valuable information that help identifying critical nodes and edges in the global networks (Estoup and Guillemaud 2010, Cristescu 2015). Historical records and genetic markers are the two major sources of information of this corpus of knowledge on Anthropocene historical phylogeography. With the advances of molecular genetics tools, the genealogy of these introductions events could be revisited and empowered. Due to their idiosyncrasy and intimate association with the contingency of human trades and activities, understanding the invasion and domestication routes require particular statistical tools (Fraimout et al. 2017). Because it encompasses all these theoretical, ecological and economical implications, I am pleased to recommend the readers of PCI Zoology this article by Mallez et al. (2021) on pine wood nematode invasion route inference from genetic markers using Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) methods. Economically and ecologically, this pest, is responsible for killing millions of pines worldwide each year. The results show these damages and the global genetic patterns are due to few events of successful introductions. The authors consider that this low probability of introductions success reinforces the idea that quarantine measures are efficient. This is illustrated in Europe where the pine-worm has been quarantined successfully in the Iberian Peninsula since 1999. Another relevant conclusion is that hybridization between invasive populations have not been observed and implied in the invasion process. Finally the present study reinforced the role of Asiatic bridgehead populations in invasion process including in Europe. Methodologically, for the first time, ABC was applied to this species. A total of 310 individual sequences were added to the Mallez et al. (2015) microsatellite dataset. Fraimoult et al. (2017) showed the interest to apply random forest to improve scenario selection in ABC framework. This method, implemented in the DiYABC software (Collin et al. 2020) for invasion route scenario selection allows to handle more complex scenario alternatives and was used in this study. In this article by Mallez et al. (2021), you will also find a clear illustration of the step-by-step approach to select scenario using ABC techniques (Lombaert et al. 2014). The rationale is to reduce number of scenario to be tested by assuming that most recent invasions cannot be the source of the most ancient invasions and to use posterior results on most ancient routes as prior hypothesis to distinguish following invasions. The other simplification is to perform classical population genetic analysis to characterize genetic units and representative populations prior to invasion routes scenarios selection by ABC. Yet, even when using the most advanced Bayesian inference methods, it is recognized by the authors that the method can be pushed to its statistical power limits. The method is appropriate when population show strong inter-population genetic structure. But the high number of differentiated populations in native area can be problematic since it is generally associated to incomplete sampling scheme. The hypothesis of ghost populations source allowed to bypass this difficulty, but the authors consider simulation studies are needed to assess the joint effect of genetic diversity and number of genetic markers on the inference results in such situation. Also the need to use a stepwise approach to reduce the number of scenario to test has to be considered with caution. Scenarios that are not selected but have non negligible posterior, cannot be ruled out in the constitution of next step scenarios hypotheses. Due to its interest to understand this major facet of Anthropocene, reconstruction of invasion routes should be more considered as a guide to damper biological homogenization process. References Collin, F.-D., Durif, G., Raynal, L., Lombaert, E., Gautier, M., Vitalis, R., Marin, J.-M. and Estoup, A. (2020) Extending Approximate Bayesian Computation with Supervised Machine Learning to infer demographic history from genetic polymorphisms using DIYABC Random Forest. Authorea. doi: https://doi.org/10.22541/au.159480722.26357192 Cristescu, M.E. (2015) Genetic reconstructions of invasion history. Molecular Ecology, 24, 2212–2225. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.13117 Estoup, A. and Guillemaud, T., (2010) Reconstructing routes of invasion using genetic data: Why, how and so what? Molecular Ecology, 9, 4113-4130. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04773.x Fraimout, A., Debat, V., Fellous, S., Hufbauer, R.A., Foucaud, J., Pudlo, P., Marin, J.M., Price, D.K., Cattel, J., Chen, X., Deprá, M., Duyck, P.F., Guedot, C., Kenis, M., Kimura, M.T., Loeb, G., Loiseau, A., Martinez-Sañudo, I., Pascual, M., Richmond, M.P., Shearer, P., Singh, N., Tamura, K., Xuéreb, A., Zhang, J., Estoup, A. and Nielsen, R. (2017) Deciphering the routes of invasion of Drosophila suzukii by Means of ABC Random Forest. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 34, 980-996. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msx050 Jaksic, F.M. and Castro, S.A. (2021). Biological Invasions in the Anthropocene, in: Jaksic, F.M., Castro, S.A. (Eds.), Biological Invasions in the South American Anthropocene: Global Causes and Local Impacts. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 19-47. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56379-0_2 Lombaert, E., Guillemaud, T., Lundgren, J., Koch, R., Facon, B., Grez, A., Loomans, A., Malausa, T., Nedved, O., Rhule, E., Staverlokk, A., Steenberg, T. and Estoup, A. (2014) Complementarity of statistical treatments to reconstruct worldwide routes of invasion: The case of the Asian ladybird Harmonia axyridis. Molecular Ecology, 23, 5979-5997. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12989 Mack, R.N., Simberloff, D., Lonsdale, M.W., Evans, H., Clout, M., Bazzaz, F.A. (2000) Biotic Invasions : Causes , Epidemiology , Global Consequences , and Control. Ecological Applications, 10, 689-710. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[0689:BICEGC]2.0.CO;2 Mallez, S., Castagnone, C., Lombaert, E., Castagnone-Sereno, P. and Guillemaud, T. (2021) Inference of the worldwide invasion routes of the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus using approximate Bayesian computation analysis. bioRxiv, 452326, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Zoology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/452326 | Inference of the worldwide invasion routes of the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus using approximate Bayesian computation analysis | Sophie Mallez, Chantal Castagnone, Eric Lombaert, Philippe Castagnone-Sereno, Thomas Guillemaud | <p>Population genetics have been greatly beneficial to improve knowledge about biological invasions. Model-based genetic inference methods, such as approximate Bayesian computation (ABC), have brought this improvement to a higher level and are now... |  | Biogeography, Biological invasions, Ecology, Evolution, Genetics/Genomics, Herbivores, Invertebrates, Molecular biology, Nematology | Stéphane Dupas | 2020-09-15 10:59:41 | View | |

10 Mar 2022

Analyses of symbiotic bacterial communities in the plant pest Bemisia tabaci reveal high prevalence of Candidatus Hemipteriphilus asiaticus on the African continentLaurence Mouton, Helene Henri, Rahim Romba, Zainab Belgaidi, Olivier Gnankine, Fabrice Vavre https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.06.463217Cross-continents whitefly secondary symbiont revealed by metabarcodingRecommended by Yuval Gottlieb based on reviews by François Renoz, Vincent Hervé and 1 anonymous reviewerWhiteflies are serious global pests that feed on phloem sap of many agricultural crop plants. Like other phloem feeders, whiteflies rely on a primary-symbiont to supply their poor, sugar-based diet. Over time, the genomes of primary-symbionts become degraded, and they are either been replaced or complemented by co-hosted secondary-symbionts (McCutcheon and Moran 2012). In Bemisia tabaci species complex, the primary-symbiont is Candidatus Portiera aleyrodidarium, with seven secondary-symbionts that have been described to date. The prevalence and dynamics of these secondary-symbionts have been studied in various whitefly populations and genetic groups around the world, and certain combinations are determined under specific biotic and environmental factors (Zchori-Fein et al. 2014). To understand the potential metabolic or other interactions of various secondary-symbionts with Ca. Portiera aleyrodidarium and the hosts, Mouton et al. used metabarcoding approach and diagnostic PCR confirmation, to describe symbiont compositions in a collection of whiteflies from eight populations with four genetic groups in Burkina Faso. They found that one of the previously recorded secondary-symbiont from Asian whitefly populations, Candidatus Hemipteriphilus asiaticus, is also found in the tested African whiteflies. The newly identified Ca. Hemipteriphilus asiaticus forms a different strain than the ones described in Asia, and is found in high prevalence in six of the tested populations and in three genetic groups. They also showed that Portiera densities are not affected by the presence of Ca. Hemipteriphilus asiaticus. The authors suggest that based on its high prevalence, Ca. Hemipteriphilus asiaticus may benefit certain whitefly populations, however, there is no attempt to test this assumption or to relate it to environmental factors, or to identify the source of introduction. Mouton et al. bring new perspectives to the study of complex hemipteran symbioses, emphasizing the need to use both unbiased approaches such as metabarcoding, together with a priori methods such as PCR, in order to receive a complete description of symbiont population structures. Their findings are awaiting future screens for this secondary-symbiont, as well as its functional genomics and experimental manipulations to clarify its role. Discoveries on whitefly-symbionts delicate interactions are required to develop alternative control strategies for this worldly devastating pest. References McCutcheon JP, Moran NA (2012) Extreme genome reduction in symbiotic bacteria. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 10, 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2670 Mouton L, Henri H, Romba R, Belgaidi Z, Gnankiné O, Vavre F (2022) Analyses of symbiotic bacterial communities in the plant pest Bemisia tabaci reveal high prevalence of Candidatus Hemipteriphilus asiaticus on the African continent. bioRxiv, 2021.10.06.463217, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.06.463217 Zchori-Fein E, Lahav T, Freilich S (2014) Variations in the identity and complexity of endosymbiont combinations in whitefly hosts. Frontiers in Microbiology, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00310 | Analyses of symbiotic bacterial communities in the plant pest Bemisia tabaci reveal high prevalence of Candidatus Hemipteriphilus asiaticus on the African continent | Laurence Mouton, Helene Henri, Rahim Romba, Zainab Belgaidi, Olivier Gnankine, Fabrice Vavre | <p style="text-align: justify;">Microbial symbionts are widespread in insects and some of them have been associated to adaptive changes. Primary symbionts (P-symbionts) have a nutritional role that allows their hosts to feed on unbalanced diets (p... |  | Biological invasions, Pest management, Symbiosis | Yuval Gottlieb | 2021-10-11 17:45:22 | View | |

27 Apr 2023

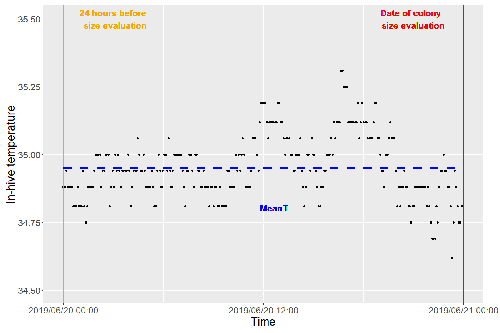

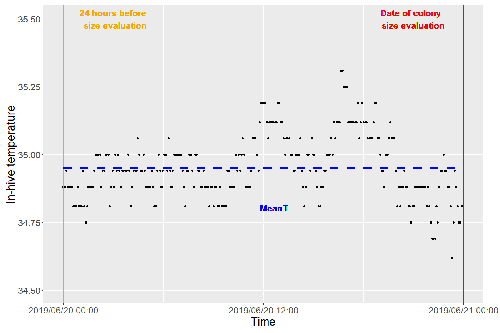

Brood thermoregulation effectivenessis positively linked to the amount of brood but not to the number of bees in honeybee coloniesUgoline Godeau, Maryline Pioz, Olivier Martin, Charlotte Rüger, Didier Crauser, Yves Le Conte, Mickael Henry, Cédric Alaux https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/9mwyePrecision and accuracy of honeybee thermoregulationRecommended by Michael Lattorff based on reviews by Jakob Wegener and Christopher Mayack based on reviews by Jakob Wegener and Christopher Mayack

The Western honeybee, Apis mellifera L., is one of the best-studied social insects. It shows a reproductive division of labour, cooperative brood care, and age-related polyethism. Furthermore, honeybees regulate the temperature in the hive. Although bees are invertebrates that are usually ectothermic, this is still true for individual worker bees, but the colony maintains a very narrow range of temperature, especially within the brood nest. This is quite important as the development of individuals is dependent on ambient temperature, with higher temperatures resulting in accelerated development and vice versa. In honeybees, a feedback mechanism couples developmental temperature and the foraging behaviour of the colony and the future population development (Tautz et al., 2003). Bees raised under lower temperatures are more likely to perform in-hive tasks, while bees raised under higher temperatures are better foragers. To maintain optimal levels of worker population growth and foraging rates, it is adaptive to regulate temperature to ensure optimal levels of developing brood. Moreover, this allows honeybees to decouple the internal developmental processes from ambient temperatures enhancing the ecological success of the species. In every system of thermoregulation, whether it is endothermic under the utilization of energetic resources as in mammals or the honeybee or ectothermic as in lower vertebrates and invertebrates through differential exposure to varying environmental temperature gradients, there is a need for precision (low variability) and accuracy (hitting the target temperature). However, in honeybees, the temperature is regulated by workers through muscle contraction and fanning of the wings and thus, a higher number of workers could be better at achieving precise and accurate temperature within the brood nest. Alternatively, the amount of brood could trigger responses with more brood available, a need for more precise and accurate temperature control. The authors aimed at testing these two important factors on the precision and accuracy of within-colony temperature regulation by monitoring 28 colonies equipped with temperature sensors for two years (Godeau et al., 2023). They found that the number of brood cells predicted the mean temperature (accuracy of thermoregulation). Other environmental factors had a small effect. However, the model incorporating these factors was weak in predicting the temperature as it overestimated temperatures in lower ranges and underestimated temperatures in higher ranges. In contrast, the variability of the target temperature (precision of thermoregulation) was positively affected by the external temperature, while all other factors did not show a significant effect. Again, the model was weak in predicting the data. Overall colony size measured in categories of the number of workers and the number of brood cells did not show major differences in variability of the mean temperature, but a slight positive effect for the number of bees on the mean temperature. Unfortunately, the temperature was a poor predictor of colony size. The latter is important as the remote control of beehives using Internet of Things (IoT) technologies get more and more incorporated into beekeeping management. These IoT technologies and their success are dependent on good proxies for the control of the status of the colony. Amongst the factors to monitor, the colony size (number of bees and/or amount of brood) is extremely important, but temperature measurements alone will not allow us to predict colony sizes. Nevertheless, this study showed clearly that the number of brood cells is a crucial factor for the accuracy of thermoregulation in the beehive, while ambient temperature affects the precision of thermoregulation. In the view of climate change, the latter factor seems to be important, as more extreme environmental conditions in the future call for measures of mitigation to ensure the proper functioning of the bee colony, including the maintenance of homeostatic conditions inside of the nest to ensure the delivery of the ecosystem service of pollination. REFERENCES Godeau U, Pioz M, Martin O, Rüger C, Crauser D, Le Conte Y, Henry M, Alaux C (2023) Brood thermoregulation effectiveness is positively linked to the amount of brood but not to the number of bees in honeybee colonies. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/9mwye Tautz J, Maier S, Claudia Groh C, Wolfgang Rössler W, Brockmann A (2003) Behavioral performance in adult honey bees is influenced by the temperature experienced during their pupal development. PNAS 100: 7343–7347. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1232346100 | Brood thermoregulation effectivenessis positively linked to the amount of brood but not to the number of bees in honeybee colonies | Ugoline Godeau, Maryline Pioz, Olivier Martin, Charlotte Rüger, Didier Crauser, Yves Le Conte, Mickael Henry, Cédric Alaux | <p style="text-align: justify;">To ensure the optimal development of brood, a honeybee colony needs to regulate its temperature within a certain range of values (thermoregulation), regardless of environmental changes in biotic and abiotic factors.... |  | Biology, Conservation biology, Demography/population dynamics, Ecology, Insecta | Michael Lattorff | Mauricio Daniel Beranek | 2022-07-06 09:20:10 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Dominique Adriaens

Ellen Decaestecker

Benoit Facon

Isabelle Schon

Emmanuel Toussaint

Bertanne Visser