Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * ▲ | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

03 Jul 2020

The 'Noble false widow' spider Steatoda nobilis is an emerging public health and ecological threatHambler, C. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/axbd4How the noble false widow spider Steatoda nobilis can turn out to be a rising public health and ecological concernRecommended by Etienne Bilgo based on reviews by Michel Dugon and 2 anonymous reviewers"The noble false widow spider Steatoda nobilis is an emerging public health and ecological threat" by Clive Hambler (2020) is an appealing article discussing important aspects of the ecology and distribution of a medically significant spider, and the health concerns it raises. References [1] Hambler, C. (2020). The “Noble false widow” spider Steatoda nobilis is an emerging public health and ecological threat. OSF Preprints, axbd4, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. doi: 10.31219/osf.io/axbd4 | The 'Noble false widow' spider Steatoda nobilis is an emerging public health and ecological threat | Hambler, C. | <p>*Steatoda nobilis*, the 'Noble false widow' spider, has undergone massive population growth in southern Britain and Ireland, at least since 1990. It is greatly under-recorded in Britain and possibly globally. Now often the dominant spider on an... |  | Arachnids, Behavior, Biogeography, Biological invasions, Conservation biology, Demography/population dynamics, Ecology, Medical entomology, Methodology, Pest management, Toxicology, Veterinary entomology | Etienne Bilgo | 2019-06-28 18:26:05 | View | |

27 Apr 2023

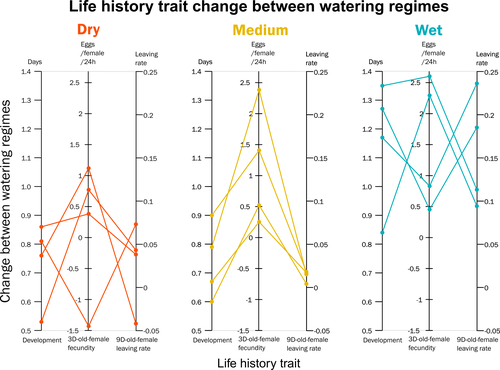

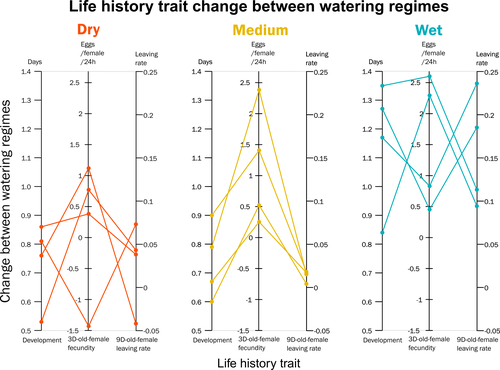

Climate of origin influences how a herbivorous mite responds to drought-stressed host plantsAlain Migeon, Philippe Auger, Odile Fossati-Gaschignard, Ruth A. Hufbauer, Maëva Miranda, Ghais Zriki, Maria Navajas https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.21.465244Not all spider-mites respond in the same way to droughtRecommended by Inês Fragata and Raul Costa-Pereira based on reviews by Bastien Castagneyrol and 2 anonymous reviewersBiotic interactions are often shaped by abiotic factors (Liu and Gaines 2022). Although this notion is not new in ecology and evolutionary biology, we are still far from a thorough understanding of how biotic interactions change along abiotic gradients in space and time. This is particularly challenging because abiotic factors can affect organisms and their interactions in multiple – direct or indirect – ways. For example, because abiotic conditions strongly determine how energy enters biological systems via producers, their effects can propagate through entire food webs, from the bottom to the top (O’Connor 2009, Gilbert et al 2019). Understanding how biological diversity - both within and across species - is shaped by the indirect effects of environmental conditions is a timely question as climate change and anthropogenic activities have been altering temperature and water availability across different ecosystems. Motivated by the current water crisis and severe droughts predicted for the near future worldwide (du Plessis 2019), Migeon et al. (2023) investigated how water limitation on producers scales up to affect life-history patterns of a widespread crop pest, the spider mite Tetranychus urticae. The authors sampled spider mite populations (n = 12) along a striking gradient of climatic conditions (>16 degrees of latitude) in Europe. After letting mites acclimate to lab conditions for several generations, the authors performed a common garden experiment to quantify how the life-history traits of mite populations from different locations respond to drought stress in their host plants. Curiously, the authors found that, when reared on drought-stressed plants, mites tended to develop faster, had higher fecundity and lower dispersion rates. This response was in line with some results obtained previously with Tetranychus species (e.g. Ximénez-Embun et al 2016). Importantly, despite some experimental caveats in the experimental design, which makes it difficult to completely disentangle the specific effects of location vs. environmental noise, results suggest the climate that populations originally experienced was also an important determinant of the plastic response in these herbivores. In fact, populations from wetter and colder regions showed a steeper change in drought response, while populations from arid climates showed a shallower response. This interesting result suggests the importance of intraspecific (between-populations) variation in the response to drought, which might be explained by the climatic heterogeneity in space throughout the evolutionary history of different populations. These results become even more important in our rapidly changing world, highlighting the importance of considering genetic variation (and conditions that generate it) when predicting plastic and evolutionary responses to stressful conditions. du Plessis, A. (2019). Current and Future Water Scarcity and Stress. In: Water as an Inescapable Risk. Springer Water. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03186-2 | Climate of origin influences how a herbivorous mite responds to drought-stressed host plants | Alain Migeon, Philippe Auger, Odile Fossati-Gaschignard, Ruth A. Hufbauer, Maëva Miranda, Ghais Zriki, Maria Navajas | <p style="text-align: justify;">Drought associated with climate change can stress plants, altering their interactions with phytophagous arthropods. Drought not only impacts cultivated plants but also their parasites, which in some cases are favore... |  | Acari, Ecology, Life histories | Inês Fragata | 2021-10-22 14:56:03 | View | |

22 Jul 2020

The open bar is closed: restructuration of a native parasitoid community following successful control of an invasive pest.David Muru, Nicolas Borowiec, Marcel Thaon, Nicolas Ris, Madalina Ionela Viciriuc, Sylvie Warot, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.20.884908Raise and fall of an invasive pest and consequences for native parasitoid communitiesRecommended by Stefaniya Kamenova based on reviews by Kévin Tougeron and Miguel González Ximénez de EmbúnHost-parasitoid interactions have been the focus of extensive ecological research for decades. One the of the major reasons is the importance host-parasitoid interactions play for the biological control of crop pests. Parasitoids are the main natural regulators for a large number of economically important pest insects, and in many cases they could be the only viable crop protection strategy. Parasitoids are also integral part of complex food webs whose structure and diversity display large spatio-temporal variations [1-3]. With the increasing globalization of human activities, the generalized spread and establishment of invasive species is a major cause of disruption in local community and food web spatio-temporal dynamics. In particular, the deliberate introduction of non-native parasitoids as part of biological control programs, aiming the suppression of established, and also highly invasive crop pests, is a common practice with potentially significant, yet poorly understood effects on local food web dynamics (e.g. [4]). References [1] Eveleigh ES, McCann KS, McCarthy PC, Pollock SJ, Lucarotti CJ, Morin B, McDougall GA, Strongman DB, Huber JT, Umbanhowar J, Faria LDB (2007). Fluctuations in density of an outbreak species drive diversity cascades in food webs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 16976-16981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704301104 | The open bar is closed: restructuration of a native parasitoid community following successful control of an invasive pest. | David Muru, Nicolas Borowiec, Marcel Thaon, Nicolas Ris, Madalina Ionela Viciriuc, Sylvie Warot, Elodie Vercken | <p>The rise of the Asian chestnut gall wasp *Dryocosmus kuriphilus* in France has benefited the native community of parasitoids originally associated with oak gall wasps by becoming an additional trophic subsidy and therefore perturbing population... |  | Biocontrol, Biological invasions, Ecology, Insecta | Stefaniya Kamenova | 2019-12-31 09:08:49 | View | |

02 Nov 2021

Cuckoo male bumblebees perform slower and longer flower visits than free-living male and worker bumblebeesAlessandro Fisogni, Gherardo Bogo, François Massol, Laura Bortolotti, Marta Galloni https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4489066Cuckoo bumblebee males might reduce plant fitnessRecommended by Michael Lattorff based on reviews by Patrick Lhomme, Silvio Erler and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Patrick Lhomme, Silvio Erler and 2 anonymous reviewers

In pollinator insects, especially bees, foraging is almost exclusively performed by females due to the close linkage with brood care. They collect pollen as a protein- and lipid-rich food to feed developing larvae in solitary and social species. Bees take carbohydrate-rich nectar in small quantities to fuel their flight and carry the pollen load. To optimise the foraging flight, they tend to be flower constant, reducing the flower handling time and time among individual inflorescences (Goulson, 1999). Males of pollinator species might be found on flowers as well. As they do not collect any pollen for brood care, their foraging flights and visits to flowers might not be shaped by the selective forces that optimise the foraging flights of females. They might stay longer in individual flowers, take up nectar if needed, but might unintentionally carry pollen on their body surface (Wolf & Moritz, 2014). | Cuckoo male bumblebees perform slower and longer flower visits than free-living male and worker bumblebees | Alessandro Fisogni, Gherardo Bogo, François Massol, Laura Bortolotti, Marta Galloni | <p>Cuckoo bumblebees are a monophyletic group within the genus Bombus and social parasites of free-living bumblebees, upon which they rely to rear their offspring. Cuckoo bumblebees lack the worker caste and visit flowers primarily for their own s... |  | Behavior, Biology, Ecology, Insecta, Invertebrates, Terrestrial | Michael Lattorff | Patrick Lhomme, Seth Barribeau , Silvio Erler, Denis Michez | 2021-02-02 01:41:35 | View |

26 Apr 2023

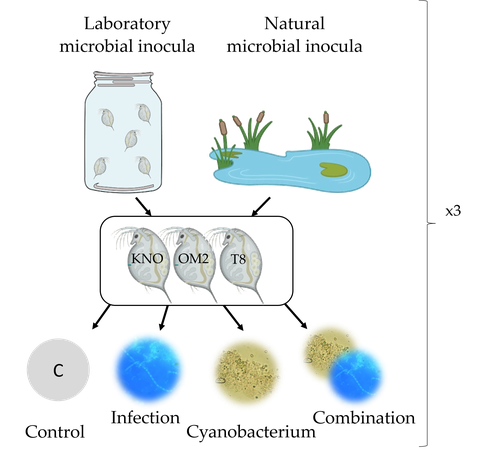

Microbiome mediated tolerance to biotic stressors: a case study of the interaction between a toxic cyanobacterium and an oomycete-like infection in Daphnia magnaShira Houwenhuyse*, Lore Bulteel*, Isabel Vanoverberghe, Anna Krzynowek, Naina Goel, Manon Coone, Silke Van den Wyngaert, Arne Sinnesael, Robby Stoks & Ellen Decaestecker https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/9n4mgMulti-stress responses depend on the microbiome in the planktonic crustacean DaphniaRecommended by Bertanne Visser and Mathilde Scheifler based on reviews by Natacha Kremer and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Natacha Kremer and 2 anonymous reviewers

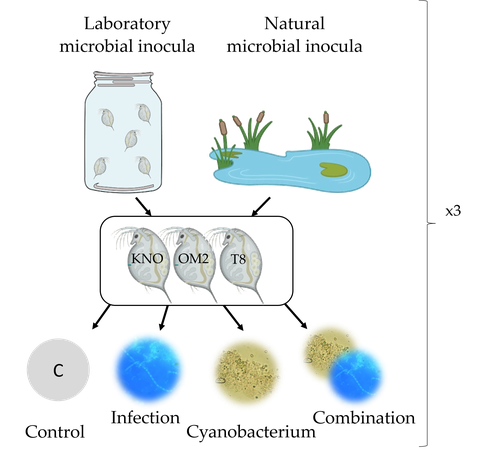

The critical role that gut microbiota play in many aspects of an animal’s life, including pathogen resistance, detoxification, digestion, and nutritional physiology, is becoming more and more apparent (Engel and Moran 2013; Lindsay et al., 2020). Gut microbiota recruitment and maintenance can be largely affected by the surrounding environment (Chandler et al., 2011; Callens et al., 2020). The environment may thus dictate gut microbiota composition and diversity, which in turn can affect organismal responses to stress. Only few studies have, however, taken the gut microbiota into account to estimate life histories in response to multiple stressors in aquatic systems (Macke et al., 2016). Houwenhuyse et al., investigate how the microbiome affects life histories in response to ecologically relevant single and multiple biotic stressors (an oomycete-like parasite, and a toxic cyanobacterium) in Daphnia magna (Houwenhuyse et al., 2023). Daphnia is an excellent model, because this aquatic system lends itself extremely well for gut microbiota transplantation and manipulation. This is due to the possibility to sterilize eggs (making them free of bacteria), horizontal transmission of bacteria from the environment, and the relative ease of culturing genetically similar Daphnia clones in large numbers. The authors use an elegant experimental design to show that the Daphnia gut microbial community differs when derived from a laboratory versus natural inoculum, the latter being more diverse. The authors subsequently show that key life history traits (survival, fecundity, and body size) depend on the stressors (and combination thereof), the microbiota (structure and diversity), and Daphnia genotype. A key finding is that Daphnia exposed to both biotic stressors show an antagonistic interaction effect on survival (being higher), but only in individuals containing laboratory gut microbiota. The exact mechanism remains to be determined, but the authors propose several interesting hypotheses as to why Daphnia with more diverse gut microbiota do less well. This could be due, for example, to increased inter-microbe competition or an increased chance of contracting opportunistic, parasitic bacteria. For Daphnia with less diverse laboratory gut microbiota, a monopolizing species may be particularly beneficial for stress tolerance. Alongside these interesting findings, the paper also provides extensive information about the gut microbiota composition (available in the supplementary files), which is a very useful resource for other researchers. Overall, this study reveals that multiple, interacting factors affect the performance of Daphnia under stressful conditions. Of importance is that laboratory studies may be based on simpler microbiota systems, meaning that stress responses measured in the laboratory may not accurately reflect what is happening in nature. REFERENCES Callens M, De Meester L, Muylaert K, Mukherjee S, Decaestecker E. The bacterioplankton community composition and a host genotype dependent occurrence of taxa shape the Daphnia magna gut bacterial community. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2020;96(8):fiaa128. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiaa128 Chandler JA, Lang JM, Bhatnagar S, Eisen JA, Kopp A. Bacterial communities of diverse Drosophila species: ecological context of a host-microbe model system. PLOS Genetics. 2011;7(9):e1002272. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002272 Engel P, Moran NA. The gut microbiota of insects - diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2013;37(5):699-735. https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6976.12025 Houwenhuyse S, Bulteel L, Vanoverberghe I, Krzynowek A, Goel N et al. Microbiome mediated tolerance to biotic stressors: a case study of the interaction between a toxic cyanobacterium and an oomycete-like infection in Daphnia magna. 2023. OSF, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/9n4mg Lindsay EC, Metcalfe NB, Llewellyn MS. The potential role of the gut microbiota in shaping host energetics and metabolic rate. Journal of Animal Ecology. 2020;89(11):2415-2426. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13327 Macke E, Tasiemski A, Massol F, Callens M, Decaestecker E. Life history and eco-evolutionary dynamics in light of the gut microbiota. Oikos. 2017;126(4):508-531. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.03900 | Microbiome mediated tolerance to biotic stressors: a case study of the interaction between a toxic cyanobacterium and an oomycete-like infection in *Daphnia magna* | Shira Houwenhuyse*, Lore Bulteel*, Isabel Vanoverberghe, Anna Krzynowek, Naina Goel, Manon Coone, Silke Van den Wyngaert, Arne Sinnesael, Robby Stoks & Ellen Decaestecker | <p style="text-align: justify;">Organisms are increasingly facing multiple, potentially interacting stressors in natural populations. The ability of populations coping with combined stressors depends on their tolerance to individual stressors and ... |  | Aquatic, Biology, Crustacea, Ecology, Life histories, Symbiosis | Bertanne Visser | 2021-05-17 16:18:18 | View | |

28 Aug 2022

A simple procedure to detect, test for the presence of stuttering, and cure stuttered data with spreadsheet programsThierry de Meeûs and Camille Noûs https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7029324Improved population genetics parameters through control for microsatellite stutteringRecommended by Michael Lattorff based on reviews by Thibaut Malausa, Fabien Halkett and Thierry Rigaud based on reviews by Thibaut Malausa, Fabien Halkett and Thierry Rigaud

Molecular markers have drastically changed and improved our understanding of biological processes. In combination with PCR, markers revolutionized the study of all organisms, even tiny insects, and eukaryotic pathogens amongst others. Microsatellite markers were the most prominent and successful ones. Their success started in the early 1990s. They were used for population genetic studies, mapping of genes and genomes, and paternity testing and inference of relatedness. Their popularity is based on some of their characteristics as codominance, the high polymorphism information content, and their ease of isolation (Schlötterer 2004). Still, microsatellites are the marker of choice for a range of non-model organisms as next-generation sequencing technologies produce a huge amount of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), but often at expense of sample size and higher costs. | A simple procedure to detect, test for the presence of stuttering, and cure stuttered data with spreadsheet programs | Thierry de Meeûs and Camille Noûs | <p>Microsatellite are powerful markers for empirical population genetics, but may be affected by amplification problems like stuttering that produces heterozygote deficits between alleles with one repeat difference. In this paper, we present a sim... | Acari, Ecology, Evolution, Genetics/Genomics, Helminthology, Invertebrates, Medical entomology, Molecular biology, Parasitology, Theoretical biology, Veterinary entomology | Michael Lattorff | 2021-12-06 14:30:47 | View | ||

09 Feb 2023

A novel nematode species from the Siberian permafrost shares adaptive mechanisms for cryptobiotic survival with C. elegans dauer larvaAnastasia Shatilovich, Vamshidhar R. Gade, Martin Pippel, Tarja T. Hoffmeyer, Alexei V. Tchesunov, Lewis Stevens, Sylke Winkler, Graham M. Hughes, Sofia Traikov, Michael Hiller, Elizaveta Rivkina, Philipp H. Schiffer, Eugene W Myers, Teymuras V. Kurzchalia https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.28.478251A novel nematode species from the Siberian permafrost shares adaptive mechanisms for cryptobiotic survival with C. elegans dauer larvaRecommended by Isa Schon based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersThis article [1] investigated two nematode genera, Panagrolaimus and Plectus, from the Siberian permafrost to unravel the adaptations allowing them to survive cryptobiosis; radio carbon dating showed that the individuals of Panagrolaimus had been in cryobiosis in Siberia for as long as 46,000 years! I was impressed by the multidisciplinary approach of this study, including morphological as well as phylogenetic and -genomic analyses to describe a new species. In triploids as some of the species studied here, it is quite challenging to assemble a novel genome. The authors furthermore not only managed to successfully reanimate the Siberian specimens but could also expose them to repeated freezing and desiccation in the lab, not an easy task. This study reports some amazing discoveries - comparing the molecular toolkits between C. elegans and Panagrolaimus and Plectus revealed that several components were orthologues. Likewise, some of the biochemical mechanisms for surviving freezing in the lab turned out to be similar for C. elegans and the Siberian nematodes. This study thus provides strong evidence that nematodes developed specific mechanisms allowing them to stay in cryobiosis over very long times. A surprising additional experimental result concerns the well-studied C. elegans - dauer larvae of this species can stay viable much longer after periods of animated suspension than previously thought. I highly recommend this article as it is an important contribution to the fields of evolution and molecular biology. This study greatly advanced our understanding of how nematodes could have adapted to cryobiosis. The applied techniques could also be useful for studying similar research questions in other organisms. Reference [1] Shatilovich A, Gade VR, Pippel M, Hoffmeyer TT, Tchesunov AV, Stevens L, Winkler S, Hughes GM, Traikov S, Hiller M, Rivkina E, Schiffer PH, Myers EW, Kurzchalia TV (2023) A novel nematode species from the Siberian permafrost shares adaptive mechanisms for cryptobiotic survival with C. elegans dauer larva. bioRxiv, 2022.01.28.478251, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.28.478251 | A novel nematode species from the Siberian permafrost shares adaptive mechanisms for cryptobiotic survival with C. elegans dauer larva | Anastasia Shatilovich, Vamshidhar R. Gade, Martin Pippel, Tarja T. Hoffmeyer, Alexei V. Tchesunov, Lewis Stevens, Sylke Winkler, Graham M. Hughes, Sofia Traikov, Michael Hiller, Elizaveta Rivkina, Philipp H. Schiffer, Eugene W Myers, Teymuras V. K... | <p style="text-align: justify;">Some organisms in nature have developed the ability to enter a state of suspended metabolism called cryptobiosis1 when environmental conditions are unfavorable. This state-transition requires the execution of comple... |  | Ecology, Evolution, Genetics/Genomics | Isa Schon | 2022-05-20 14:32:02 | View | |

27 Apr 2023

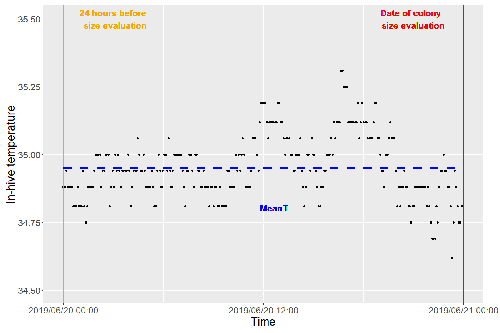

Brood thermoregulation effectivenessis positively linked to the amount of brood but not to the number of bees in honeybee coloniesUgoline Godeau, Maryline Pioz, Olivier Martin, Charlotte Rüger, Didier Crauser, Yves Le Conte, Mickael Henry, Cédric Alaux https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/9mwyePrecision and accuracy of honeybee thermoregulationRecommended by Michael Lattorff based on reviews by Jakob Wegener and Christopher Mayack based on reviews by Jakob Wegener and Christopher Mayack

The Western honeybee, Apis mellifera L., is one of the best-studied social insects. It shows a reproductive division of labour, cooperative brood care, and age-related polyethism. Furthermore, honeybees regulate the temperature in the hive. Although bees are invertebrates that are usually ectothermic, this is still true for individual worker bees, but the colony maintains a very narrow range of temperature, especially within the brood nest. This is quite important as the development of individuals is dependent on ambient temperature, with higher temperatures resulting in accelerated development and vice versa. In honeybees, a feedback mechanism couples developmental temperature and the foraging behaviour of the colony and the future population development (Tautz et al., 2003). Bees raised under lower temperatures are more likely to perform in-hive tasks, while bees raised under higher temperatures are better foragers. To maintain optimal levels of worker population growth and foraging rates, it is adaptive to regulate temperature to ensure optimal levels of developing brood. Moreover, this allows honeybees to decouple the internal developmental processes from ambient temperatures enhancing the ecological success of the species. In every system of thermoregulation, whether it is endothermic under the utilization of energetic resources as in mammals or the honeybee or ectothermic as in lower vertebrates and invertebrates through differential exposure to varying environmental temperature gradients, there is a need for precision (low variability) and accuracy (hitting the target temperature). However, in honeybees, the temperature is regulated by workers through muscle contraction and fanning of the wings and thus, a higher number of workers could be better at achieving precise and accurate temperature within the brood nest. Alternatively, the amount of brood could trigger responses with more brood available, a need for more precise and accurate temperature control. The authors aimed at testing these two important factors on the precision and accuracy of within-colony temperature regulation by monitoring 28 colonies equipped with temperature sensors for two years (Godeau et al., 2023). They found that the number of brood cells predicted the mean temperature (accuracy of thermoregulation). Other environmental factors had a small effect. However, the model incorporating these factors was weak in predicting the temperature as it overestimated temperatures in lower ranges and underestimated temperatures in higher ranges. In contrast, the variability of the target temperature (precision of thermoregulation) was positively affected by the external temperature, while all other factors did not show a significant effect. Again, the model was weak in predicting the data. Overall colony size measured in categories of the number of workers and the number of brood cells did not show major differences in variability of the mean temperature, but a slight positive effect for the number of bees on the mean temperature. Unfortunately, the temperature was a poor predictor of colony size. The latter is important as the remote control of beehives using Internet of Things (IoT) technologies get more and more incorporated into beekeeping management. These IoT technologies and their success are dependent on good proxies for the control of the status of the colony. Amongst the factors to monitor, the colony size (number of bees and/or amount of brood) is extremely important, but temperature measurements alone will not allow us to predict colony sizes. Nevertheless, this study showed clearly that the number of brood cells is a crucial factor for the accuracy of thermoregulation in the beehive, while ambient temperature affects the precision of thermoregulation. In the view of climate change, the latter factor seems to be important, as more extreme environmental conditions in the future call for measures of mitigation to ensure the proper functioning of the bee colony, including the maintenance of homeostatic conditions inside of the nest to ensure the delivery of the ecosystem service of pollination. REFERENCES Godeau U, Pioz M, Martin O, Rüger C, Crauser D, Le Conte Y, Henry M, Alaux C (2023) Brood thermoregulation effectiveness is positively linked to the amount of brood but not to the number of bees in honeybee colonies. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/9mwye Tautz J, Maier S, Claudia Groh C, Wolfgang Rössler W, Brockmann A (2003) Behavioral performance in adult honey bees is influenced by the temperature experienced during their pupal development. PNAS 100: 7343–7347. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1232346100 | Brood thermoregulation effectivenessis positively linked to the amount of brood but not to the number of bees in honeybee colonies | Ugoline Godeau, Maryline Pioz, Olivier Martin, Charlotte Rüger, Didier Crauser, Yves Le Conte, Mickael Henry, Cédric Alaux | <p style="text-align: justify;">To ensure the optimal development of brood, a honeybee colony needs to regulate its temperature within a certain range of values (thermoregulation), regardless of environmental changes in biotic and abiotic factors.... |  | Biology, Conservation biology, Demography/population dynamics, Ecology, Insecta | Michael Lattorff | Mauricio Daniel Beranek | 2022-07-06 09:20:10 | View |

30 Nov 2022

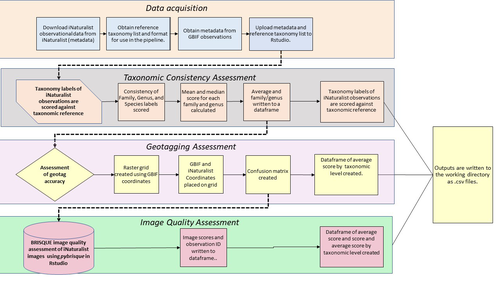

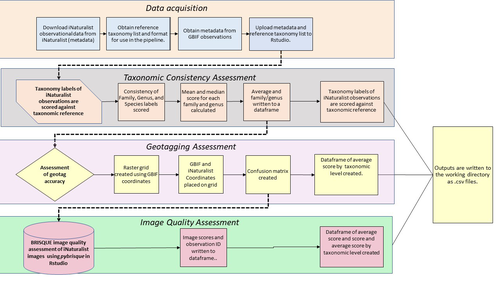

A pipeline for assessing the quality of images and metadata from crowd-sourced databases.Jackie Billotte https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.29.490112Harnessing the full potential of iNaturalist and other databasesRecommended by Matthias Foellmer based on reviews by Clive Hambler and Catherine ScottThe popularity of iNaturalist and other online biodiversity databases to which the general public and specialists alike contribute observations has skyrocketed in recent years (Dance 2022). The AI-based algorithms (computer vision) which provide the first identification of a given organism on an uploaded photograph have become very sophisticated, suggesting initial identifications often down to species level with a surprisingly high degree of accuracy. The initial identifications are then confirmed or improved by feedback from the community, which works particularly well for organismal groups to which many active community members contribute, such as the birds. Hence, providing initial observations and identifying observations of others, as well as browsing the recorded biodiversity for given locales or the range of occurrences of individual taxa has become a meaningful and satisfying experience for the interested naturalist. Furthermore, several research studies have now been published relying on observations uploaded to iNaturalist (Szentivanyi and Vincze 2022). However, using the enormous amount of natural history data available on iNaturalist in a systematic way has remained challenging, since this requires not only retrieving numerous observations from the database (in the hundreds or even thousands), but also some level of transparent quality control. Billotte (2022) provides a protocol and R scripts for the quality assessment of downloaded observations from iNaturalist, allowing an efficient and reproducible stepwise approach to prepare a high-quality data set for further analysis. First, observations with their associated metadata are downloaded from iNaturalist, along with the corresponding entries from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). In addition, a taxonomic reference list is obtained (these are available online for many taxa), which is used to assess the taxonomic consistency in the dataset. Second, the geo-tagging is assessed by comparing the iNaturalist and GBIF metadata. Lastly, the image quality is assessed using pyBRISQUE. The approach is illustrated using spiders (Araneae) as an example. Spiders are a very diverse taxon and an excellent taxonomic reference list is available (World Spider Catalogue 2022). However, spiders are not well known to most non-specialists, and it is not easy to take good pictures of spiders without using professional equipment. Therefore, the ability of iNaturalist’s computer vision to provide identifications is limited to this date and the community of specialists active on iNaturalist is comparatively small. Hence, spiders are a good taxon to demonstrate how the pipeline results in a quality-controlled dataset based on crowed-sourced data. Importantly, the software employed is free to use, although inevitably, the initial learning curve to use R scripts can be steep, depending on prior expertise with R/RStudio. Furthermore, the approach is employable with databases other than iNaturalist. In summary, Billotte's (2022) pipeline allows researchers to use the wealth of observations on iNaturalist and other databases to produce large metadata and image datasets of high-quality in a reproducible way. This should pave the way for more studies, which could include, for example, the assessment of range expansions of invasive species or the evaluation of the presence of endangered species, potentially supporting conservation efforts. References Billotte J (2022) A pipeline for assessing the quality of images and metadata from crowd-sourced databases. BiorXiv, 2022.04.29.490112, ver 5 peer reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.29.490112 Dance A (2022) Community science draws on the power of the crowd. Nature, 609, 641–643. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-02921-3 Szentivanyi T, Vincze O (2022) Tracking wildlife diseases using community science: an example through toad myiasis. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 68, 74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-022-01623-5 World Spider Catalog (2022). World Spider Catalog. Version 23.5. Natural History Museum Bern, online at http://wsc.nmbe.ch. https://doi.org/10.24436/2 | A pipeline for assessing the quality of images and metadata from crowd-sourced databases. | Jackie Billotte | <p style="text-align: justify;">Crowd-sourced biodiversity databases provide easy access to data and images for ecological education and research. One concern with using publicly sourced databases; however, is the quality of their images, taxonomi... |  | Arachnids, Biodiversity, Biology, Conservation biology, Ecology, Insecta, Invertebrates | Matthias Foellmer | 2022-05-03 00:18:23 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Dominique Adriaens

Ellen Decaestecker

Benoit Facon

Isabelle Schon

Emmanuel Toussaint

Bertanne Visser