Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▼ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

10 Jan 2020

Culex saltanensis and Culex interfor (Diptera: Culicidae) are susceptible and competent to transmit St. Louis encephalitis virus (Flavivirus: Flaviviridae) in central ArgentinaBeranek MD, Quaglia AI, Peralta GC, Flores FS, Stein M, Diaz LA, Almirón WR and Contigiani MS https://doi.org/10.1101/722579Multiple vector species may be responsible for transmission of Saint Louis Encephalatis Virus in ArgentinaRecommended by Anna Cohuet based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersMedical and veterinary entomology is a discipline that deals with the role of insects on human and animal health. A primary objective is the identification of vectors that transmit pathogens. This is the aim of Beranek and co-authors in their study [1]. They focus on mosquito vector species responsible for transmission of St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV), an arbovirus that circulates in avian species but can incidentally occur in dead end mammal hosts such as humans, inducing symptoms and sometimes fatalities. Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus is known as the most common vector, but other species are suspected to also participate in transmission. Among them Culex saltanensis and Culex interfor have been found to be infected by the virus in the context of outbreaks. The fact that field collected mosquitoes carry virus particles is not evidence for their vector competence: indeed to be a competent vector, the mosquito must not only carry the virus, but also the virus must be able to replicate within the vector, overcome multiple barriers (until the salivary glands) and be present at sufficient titre within the saliva. This paper describes the experiments implemented to evaluate the vector competence of Cx. saltanensis and Cx. interfor from ingestion of SLEV to release within the saliva. Females emerged from field-collected eggs of Cx. pipiens quinquefasciatus, Cx. saltanensis and Cx. interfor were allowed to feed on SLEV infected chicks and viral development was measured by using (i) the infection rate (presence/absence of virus in the mosquito abdomen), (ii) the dissemination rate (presence/absence of virus in mosquito legs), and (iii) the transmission rate (presence/absence of virus in mosquito saliva). The sample size for each species is limited because of difficulties for collecting, feeding and maintaining large numbers of individuals from field populations, however the results are sufficient to show that this strain of SLEV is able to disseminate and be expelled in the saliva of mosquitoes of the three species at similar viral loads. This work therefore provides evidence that Cx saltanensis and Cx interfor are competent species for SLEV to complete its life-cycle. Vector competence does not directly correlate with the ability to transmit in real life as the actual vectorial capacity also depends on the contact between the infectious vertebrate hosts, the mosquito life expectancy and the extrinsic incubation period of the viruses. The present study does not deal with these characteristics, which remain to be investigated to complete the picture of the role of Cx saltanensis and Cx interfor in SLEV transmission. However, this study provides proof of principle that that SLEV can complete it’s life-cycle in Cx saltanensis and Cx interfor. Combined with previous knowledge on their feeding preference, this highlights their potential role as bridge vectors between birds and mammals. These results have important implications for epidemiological forecasting and disease management. Public health strategies should consider the diversity of vectors in surveillance and control of SLEV. References | Culex saltanensis and Culex interfor (Diptera: Culicidae) are susceptible and competent to transmit St. Louis encephalitis virus (Flavivirus: Flaviviridae) in central Argentina | Beranek MD, Quaglia AI, Peralta GC, Flores FS, Stein M, Diaz LA, Almirón WR and Contigiani MS | <p>Infectious diseases caused by mosquito-borne viruses constitute health and economic problems worldwide. St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV) is endemic and autochthonous in the American continent. Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus is the primary ur... |  | Medical entomology | Anna Cohuet | 2019-08-03 00:56:38 | View | |

09 Jul 2021

First detection of herpesvirus and mycoplasma in free-ranging Hermann tortoises (Testudo hermanni), and in potential pet vectorsJean-marie Ballouard, Xavier Bonnet, Julie Jourdan, Albert Martinez-Silvestre, Stephane Gagno, Brieuc Fertard, Sebastien Caron https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.22.427726Welfare threatened speciesRecommended by Peter Galbusera based on reviews by Francis Vercammen and Maria Luisa MarenzoniWildlife is increasingly threatened by drops in number of individuals and populations, and eventually by extinction. Besides loss of habitat, persecution, pet trade,… a decrease in individual health status is an important factor to consider. In this article, Ballouard et al (2021) perform a thorough analysis on the prevalence of two pathogens (herpes virus and mycoplasma) in (mainly) Western Hermann’s tortoises in south-east France. This endangered species was suspected to suffer from infections obtained through released/escaped pet tortoises. By incorporating samples of captive as well as wild tortoises, they convincingly confirm this and identify some possible ‘pet’ vectors. In February this year, a review paper on health assessments in wildlife was published (Kophamel et al 2021). Amongst others, it shows reptilia/chelonia are relatively well-represented among publications. It also contains a useful conceptual framework, in order to improve the quality of the assessments to better facilitate conservation planning. The recommended manuscript (Ballouard et al 2021) adheres to many aspects of this framework (e.g. minimum sample size, risk status, …) while others might need more (future) attention. For example, climate/environmental changes are likely to increase stress levels, which could lead to more disease symptoms. So, follow-up studies should consider conducting endocrinological investigations to estimate/monitor stress levels. Kophamel et al (2021) also stress the importance of strategic international collaboration, which may allow more testing of Eastern Hermann’s Tortoise, as these were shown to be infected by mycoplasma. The genetic health of individuals/populations shouldn’t be forgotten in health/stress assessments. As noted by Ballouard et al (2021), threatened species often have low genetic diversity which makes them more vulnerable to diseases. So, it would be interesting to link the infection data with (individual) genetic characteristics. In future research, the samples collected for this paper could fit that purpose. Finally, it is expected that this paper will contribute to the conservation management strategy of the Hermann’s tortoises. As such, it will be interesting to see how the results of the current paper will be implemented in the ‘field’. As the infections are likely caused by releases/escaped pets and as treating the wild animals is difficult, preventing them from getting infected through pets seems a priority. Awareness building among pet holders and monitoring/treating pets should be highly effective. References Ballouard J-M, Bonnet X, Jourdan J, Martinez-Silvestre A, Gagno S, Fertard B, Caron S (2021) First detection of herpesvirus and mycoplasma in free-ranging Hermann’s tortoises (Testudo hermanni), and in potential pet vectors. bioRxiv, 2021.01.22.427726, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.22.427726 Kophamel S, Illing B, Ariel E, Difalco M, Skerratt LF, Hamann M, Ward LC, Méndez D, Munns SL (2021), Importance of health assessments for conservation in noncaptive wildlife. Conservation Biology. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13724 | First detection of herpesvirus and mycoplasma in free-ranging Hermann tortoises (Testudo hermanni), and in potential pet vectors | Jean-marie Ballouard, Xavier Bonnet, Julie Jourdan, Albert Martinez-Silvestre, Stephane Gagno, Brieuc Fertard, Sebastien Caron | <p style="text-align: justify;">Two types of pathogens cause highly contagious upper respiratory tract diseases (URTD) in Chelonians: testudinid herpesviruses (TeHV) and a mycoplasma (<em>Mycoplasma agassizii</em>). In captivity, these infections ... | Parasitology, Reptiles | Peter Galbusera | 2021-01-25 17:25:34 | View | ||

10 Mar 2022

Analyses of symbiotic bacterial communities in the plant pest Bemisia tabaci reveal high prevalence of Candidatus Hemipteriphilus asiaticus on the African continentLaurence Mouton, Helene Henri, Rahim Romba, Zainab Belgaidi, Olivier Gnankine, Fabrice Vavre https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.06.463217Cross-continents whitefly secondary symbiont revealed by metabarcodingRecommended by Yuval Gottlieb based on reviews by François Renoz, Vincent Hervé and 1 anonymous reviewerWhiteflies are serious global pests that feed on phloem sap of many agricultural crop plants. Like other phloem feeders, whiteflies rely on a primary-symbiont to supply their poor, sugar-based diet. Over time, the genomes of primary-symbionts become degraded, and they are either been replaced or complemented by co-hosted secondary-symbionts (McCutcheon and Moran 2012). In Bemisia tabaci species complex, the primary-symbiont is Candidatus Portiera aleyrodidarium, with seven secondary-symbionts that have been described to date. The prevalence and dynamics of these secondary-symbionts have been studied in various whitefly populations and genetic groups around the world, and certain combinations are determined under specific biotic and environmental factors (Zchori-Fein et al. 2014). To understand the potential metabolic or other interactions of various secondary-symbionts with Ca. Portiera aleyrodidarium and the hosts, Mouton et al. used metabarcoding approach and diagnostic PCR confirmation, to describe symbiont compositions in a collection of whiteflies from eight populations with four genetic groups in Burkina Faso. They found that one of the previously recorded secondary-symbiont from Asian whitefly populations, Candidatus Hemipteriphilus asiaticus, is also found in the tested African whiteflies. The newly identified Ca. Hemipteriphilus asiaticus forms a different strain than the ones described in Asia, and is found in high prevalence in six of the tested populations and in three genetic groups. They also showed that Portiera densities are not affected by the presence of Ca. Hemipteriphilus asiaticus. The authors suggest that based on its high prevalence, Ca. Hemipteriphilus asiaticus may benefit certain whitefly populations, however, there is no attempt to test this assumption or to relate it to environmental factors, or to identify the source of introduction. Mouton et al. bring new perspectives to the study of complex hemipteran symbioses, emphasizing the need to use both unbiased approaches such as metabarcoding, together with a priori methods such as PCR, in order to receive a complete description of symbiont population structures. Their findings are awaiting future screens for this secondary-symbiont, as well as its functional genomics and experimental manipulations to clarify its role. Discoveries on whitefly-symbionts delicate interactions are required to develop alternative control strategies for this worldly devastating pest. References McCutcheon JP, Moran NA (2012) Extreme genome reduction in symbiotic bacteria. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 10, 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2670 Mouton L, Henri H, Romba R, Belgaidi Z, Gnankiné O, Vavre F (2022) Analyses of symbiotic bacterial communities in the plant pest Bemisia tabaci reveal high prevalence of Candidatus Hemipteriphilus asiaticus on the African continent. bioRxiv, 2021.10.06.463217, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.06.463217 Zchori-Fein E, Lahav T, Freilich S (2014) Variations in the identity and complexity of endosymbiont combinations in whitefly hosts. Frontiers in Microbiology, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00310 | Analyses of symbiotic bacterial communities in the plant pest Bemisia tabaci reveal high prevalence of Candidatus Hemipteriphilus asiaticus on the African continent | Laurence Mouton, Helene Henri, Rahim Romba, Zainab Belgaidi, Olivier Gnankine, Fabrice Vavre | <p style="text-align: justify;">Microbial symbionts are widespread in insects and some of them have been associated to adaptive changes. Primary symbionts (P-symbionts) have a nutritional role that allows their hosts to feed on unbalanced diets (p... |  | Biological invasions, Pest management, Symbiosis | Yuval Gottlieb | 2021-10-11 17:45:22 | View | |

21 Mar 2023

Population genetics of Glossina fuscipes fuscipes from southern ChadSophie Ravel, Mahamat Hissène Mahamat, Adeline Ségard, Rafael Argiles-Herrero, Jérémy Bouyer, Jean-Baptiste Rayaisse, Philippe Solano, Brahim Guihini Mollo, Mallaye Pèka, Justin Darnas, Adrien Marie Gaston Belem, Wilfrid Yoni, Camille Noûs, Thierry de Meeûs https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7763870Population genetics of tsetse, the vector of African Trypanosomiasis, helps informing strategies for control programsRecommended by Michael Lattorff based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT), or sleeping sickness, is caused by trypanosome parasites. In sub-Saharan Africa, two forms are present, Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and T. b. rhodesiense, the former responsible for 95% of reported cases. The parasites are transmitted through a vector, Genus Glossina, also known as tsetse, which means fly in Tswana, a language from southern Africa. Through a blood meal, tsetse picks up the parasite from infected humans or animals (in animals, the parasite causes Animal African Trypanosomiasis or nagana disease). Through medical interventions and vector control programs, the burden of the disease has drastically reduced over the past two decades, so the WHO neglected tropical diseases road map targets the interruption of transmission (zero cases) for 2030 (WHO 2022). Meaningful vector control programs utilize traps for the removal of animals and for surveillance, along with different methods of spraying insecticides. However, in existing HAT risk areas, it will be essential to understand the ecology of the vector species to implement control programs in a way that areas cleared from the vector will not be reinvaded from other populations. Thus, it will be crucial to understand basic population genetics parameters related to population structure and subdivision, migration frequency and distances, population sizes, and the potential for sex-biased dispersal. The authors utilize genotyping using nine highly polymorphic microsatellite markers of samples from Chad collected in differently affected regions and at different time points (Ravel et al., 2023). Two major HAT zones exist that are targeted by vector control programs, namely Madoul and Maro, while two other areas, Timbéri and Dokoutou, are free of trypanosomes. Samples were taken before vector control programs started. The sex ratio was female-biased, most strongly in Mandoul and Maro, the zones with the lowest population density. This could be explained by resource limitation, which could be the hosts for a blood meal or the sites for larviposition. Limited resources mean that females must fly further, increasing the chance that more females are caught in traps. The effective population densities of Mandoul and Maro were low. However, there was a convergence of population density and trapping density, which might be explained by the higher preservation of flies in the high-density areas of Timbéri and Dokoutou after the first round of sampling, which can only be tested using a second sampling. The dispersal distances are the highest recorded so far, especially in Mandoul and Maro, with 20-30 km per generation. However, in Timbéri and Dokoutou, which are 50 km apart, very little exchange occurs (approx. 1-2 individuals every six months). A major contributor to this is the massive destruction of habitat that started in the early 1990s and left patchily distributed and fragmented habitats. The Mandoul zone might be safe from reinvasion after eradication, as for a successful re-establishment, either a pair of a female and male or a pregnant female are required. As the trypanosome prevalence amongst humans was 0.02 and of tsetse 0.06 (Ibrahim et al., 2021) before interventions began, medical interventions and vector control might have further reduced these levels, making a reinvasion and subsequent re-establishment of HAT very unlikely. Maro is close to the border of the Central African Republic, and the area has not been well investigated concerning refugee populations of tsetse, which could contribute to a reinvasion of the Maro zone. The higher level of genetic heterogeneity of the Maro population indicates that invasions from neighboring populations are already ongoing. This immigration could also be the reason for not detecting the bottleneck signature in the Maro population. The two HAT areas need different levels of attention while implementing vector eradication programs. While Madoul is relatively safe against reinvasion, Maro needs another type of attention, as frequent and persistent immigration might counteract eradication efforts. Thus, it is recommended that continuous tsetse suppression needs to be implemented in Maro. This study shows nicely that an in-depth knowledge of the processes within and between populations is needed to understand how these populations behave. This can be used to extrapolate, make predictions, and inform the organisations implementing vector control programs to include valuable adjustments, as in the case of Maro. Such integrative approaches can help prevent the failure of programs, potentially saving costs and preventing infections of humans and animals who might die if not treated. References Ibrahim MAM, Weber JS, Ngomtcho SCH, Signaboubo D, Berger P, Hassane HM, Kelm S (2021) Diversity of trypanosomes in humans and cattle in the HAT foci Mandoul and Maro, Southern Chad- Southern Chad-A matter of concern for zoonotic potential? PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 15, e000 323. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0009323 Ravel S, Mahamat MH, Ségard A, Argiles-Herrero R, Bouyer J, Rayaisse JB, Solano P, Mollo BG, Pèka M, Darnas J, Belem AMG, Yoni W, Noûs C, de Meeûs T (2023) Population genetics of Glossina fuscipes fuscipes from southern Chad. Zenodo, ver. 9 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7763870 WHO (2022) Trypanosomiasis, human African (sleeping sickness). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/trypanosomiasis-human-african-(sleeping-sickness), retrieved 17. March 2023 | Population genetics of Glossina fuscipes fuscipes from southern Chad | Sophie Ravel, Mahamat Hissène Mahamat, Adeline Ségard, Rafael Argiles-Herrero, Jérémy Bouyer, Jean-Baptiste Rayaisse, Philippe Solano, Brahim Guihini Mollo, Mallaye Pèka, Justin Darnas, Adrien Marie Gaston Belem, Wilfrid Yoni, Camille Noûs, Thierr... | <p>In Subsaharan Africa, tsetse flies (genus Glossina) are vectors of trypanosomes causing Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT) and Animal African Trypanosomosis (AAT). Some foci of HAT persist in Southern Chad, where a program of tsetse control wa... | Biology, Ecology, Evolution, Genetics/Genomics, Insecta, Medical entomology, Parasitology, Pest management, Veterinary entomology | Michael Lattorff | Audrey Bras | 2022-04-22 11:25:24 | View | |

05 Jan 2021

Do substrate roughness and gap distance impact gap-bridging strategies in arboreal chameleons?Allison M. Luger, Vincent Vermeylen, Anthony Herrel, Dominique Adriaens https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.260596Gap-bridging strategies in arboreal chameleonsRecommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by Simon Baeckens and 2 anonymous reviewersUntil now, very little is known about the tail use and functional performance in tail prehensile animals. Luger et al. (2020) are the first to provide explorative observations on trait related modulation of tail use, despite the lack of a sufficiently standardized data set to allow statistical testing. They described whether gap distance, perch diameter, and perch roughness influence tail use and overall locomotor behavior of the species Chamaeleo calyptratus. References Luger, A.M., Vermeylen, V., Herrel, A. and Adriaens, D. (2020) Do substrate roughness and gap distance impact gap-bridging strategies in arboreal chameleons? bioRxiv, 2020.08.21.260596, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.260596 | Do substrate roughness and gap distance impact gap-bridging strategies in arboreal chameleons? | Allison M. Luger, Vincent Vermeylen, Anthony Herrel, Dominique Adriaens | <p>Chameleons are well-equipped for an arboreal lifestyle, having ‘zygodactylous’ hands and feet as well as a fully prehensile tail. However, to what degree tail use is preferred over autopod prehension has been largely neglected. Using an indoor ... |  | Behavior, Biology, Herpetology, Reptiles, Vertebrates | Ellen Decaestecker | 2020-08-25 10:06:42 | View | |

20 Dec 2022

Non-target effects of ten essential oils on the egg parasitoid Trichogramma evanescensLouise van Oudenhove, Aurélie Cazier, Marine Fillaud, Anne-Violette Lavoir, Hicham Fatnassi, Guy Pérez, Vincent Calcagno https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.14.476310Side effects of essential oils on pest natural enemiesRecommended by Cedric Pennetier based on reviews by Olivier Roux and 2 anonymous reviewersIntegrated pest management relies on the combined use of different practices in time and/or space. The main objectives are to better control pests, not to induce too much selective pressure on resistance mechanisms present in pest populations and to minimize non-targeted effects on the ecosystem [1]. The efficiency of such a strategy requires at least additional or synergistic effects of chosen tools against targeted pest population in a specific environment. Any antagonistic effect on targeted or non-targeted organisms might reduce control effort to nil even worst. Van Oudenhove et al [2] raised the question of the interaction between botanical pesticides (BPs) and egg parasitoids. Each of these two strategies used for pest management present advantages and are described as eco-friendly. First, the use of parasitoids is a great example of biological control and is massively used in a broad range of crop production in different ecological settings. Second, BPs, especially essential oils (EOs) used for a wide range of activities on pests (repellent, antifeedant, antiovipositant, ovicidal, larvicidal and simply pesticidal) present low-toxicity to non-target vertebrates and do not last too long in the environment. Combining these two strategies might be considered as a great opportunity to better pest control with minimized impact on environment. However, EOs used to target a wide range of pest might directly or indirectly affect parasitoids. Van Oudenhove et al [2] focused their study on non-target effects of 10 essentials oils with pesticide potential on larval development and egg-seeking behaviour of five strains of the biocontrol agent Trichogramma evanescens. Within two laboratory experiments mimicing EOs fumigation (i.e. contactless EOs exposure), the authors evaluated (1) the toxicity of EOs on parasitoid development and (2) the repellent effect of these EOs on adult wasps. They confirmed that contactless exposure of EOs can (1) induce mortality during pre-imaginal development (more acute at the pupal stage) and (2) induce behavioural avoidance of EOs odour plume. These experiments ran onto five strains of T. evanescens also highlighted the variation of the effects of EOs among parasitoid strains. The complex and dynamic interaction between pest, plant, parasitoid (a natural enemy) and their environment is disturbed by EOs. EOs plumes are also dynamic and variable upon the environmental conditions. The results of van Oudenhove et al. experimentally illustrate such a complexity by describing opposite effects (repellent and attractive) of the same EO on the behaviour of two T. evanescens strains. These contrasting results led us to question more broadly the non-target effects of pest management programs based on EOs fumigation on natural enemies. Finally, the limits of this experimental study as discussed in the paper draw research avenues taking into account biotic variables such as plant chemical cues, odour plume dynamics, individual behavioural experiences and abiotic variables such as temperature, light and gravity [3] in laboratory, semi-field and field experiments. Facing such a complexity, modelling studies at fine scale in time and space have the operational objective to help farmers to choose the best IPM strategy regarding their environment (as illustrated for aphid population management in the recent review by Stell et al. [4]). But before such research effort to be undertaken, Van Oudenhove et al study [2] sounds like an alert for a cautious use of EOs in pest control programs that integrate biological control with parasitoids.

References [1] Fauvergue, X. Biocontrôle Elements Pour Une Protection Agroecologique des Cultures; Éditions Quae: Versailles, France, 2020. [2] van Oudenhove L, Cazier A, Fillaud M, Lavoir AV, Fatnassi H, Pérez G, Calcagno V. Non-target effects of ten essential oils on the egg parasitoid Trichogramma evanescens. bioRxiv 2022.01.14.476310, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.14.476310 [3] Victor Burte, Guy Perez, Faten Ayed, Géraldine Groussier, Ludovic Mailleret, Louise van Oudenhove and Vincent Calcagno (2022) Up and to the light: intra- and interspecific variability of photo- and geo-tactic oviposition preferences in genus Trichogramma, Peer Community Journal, 2: e3. https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.78 [4] Stell E, Meiss H, Lasserre-Joulin F, Therond O. Towards Predictions of Interaction Dynamics between Cereal Aphids and Their Natural Enemies: A Review. Insects 2022, 13, 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13050479 | Non-target effects of ten essential oils on the egg parasitoid Trichogramma evanescens | Louise van Oudenhove, Aurélie Cazier, Marine Fillaud, Anne-Violette Lavoir, Hicham Fatnassi, Guy Pérez, Vincent Calcagno | <p style="text-align: justify;">Essential oils (EOs) are increasingly used as biopesticides due to their insecticidal potential. This study addresses their non-target effects on a biological control agent: the egg parasitoid <em>Trichogramma evane... |  | Behavior, Biochemistry, Biocontrol, Biodiversity, Computer modelling, Conservation biology, Demography/population dynamics, Development, Ecology, Insecta, Insectivores, Invertebrates, Life histories, Methodology, Pest management, Theoretical biolo... | Cedric Pennetier | 2022-01-31 16:05:32 | View | |

08 Feb 2022

The initial response of females towards congeneric males matches the propensity to hybridise in OphthalmotilapiaMaarten Van Steenberge, Noemie Jublier, Loic Kever, Sophie Gresham, Sofie Derycke, Jos Snoeks, Eric Parmentier, Pascal Poncin, Erik Verheyen https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.07.455508Experimental evidence for asymmetrical species recognition in East African Ophthalmotilapia cichlidsRecommended by Ellen Decaestecker based on reviews by George Turner and 2 anonymous reviewersI recommend the Van Steenberge et al. study. With over 2000 endemic species, the East African cichlids are a well-established model system in speciation research (Salzburger 2018) and several models have been proposed and tested to explain how these radiations formed (Kocher 2004). Hybridization was shown to be a main driver of the rapid speciation and adaptive radiations of the East African Cichlid fishes (Seehausen 2004). However, it is obvious that unrestrained hybridization also has the potential to reduce taxonomic diversity by erasing species barriers. In the classical model of cichlid evolution, special emphasis was placed on mate preference (Kocher 2004). However, no attention was placed on species recognition, which was implicitly assumed. There is, however, more research needed on what species recognition means, especially in radiating lineages such as cichlids. In a previous study, Nevado et al. 2011 found traces of asymmetrical hybridization between members of the Lake Tanganyika radiation: the genus Ophthalmotilapia. This recommended study by Van Steenberge et al. is based on Nevado et al. (2011), which detected that in one genus of Ophthalmotilapia mitochondrial DNA ‘typical’ for one of the four species (O. nasuta) was also found in three other species (O. ventralis, O. heterodonta, and O. boops). The authors suggested that this could be explained by the fact that females of the three other species accepted O. nasuta males, but that O. nasuta females were more selective and accepted only conspecifc males. This could hence be due to asymmetric mate preferences, or by asymmetric abilities for species recognition. This is exactly what the current study by Van Steenberge et al. did. They tested the latter hypothesis by presenting females of two different Ophthalmotilapia species with con- and heterospecific males. This was tested through experiments, making use of wild specimens of two species: O. nasuta and O. ventralis. The authors assumed that if they performed classical “choice-experiments”, they would not notice the recognition effects, given that females would just select preferred, most likely conspecific, males. Instead, specimens were only briefly presented to other fishes since the authors wanted to compare differences in the ability for ‘species recognition’. In this, the authors followed Mendelson and Shaw (2012) who used “a measurable difference in behavioural response towards conspecifics as compared to heterospecifics’’ as a definition for recognition. Instead of the focus on selection/preference, they investigated if females of different species behaved differently, and hence detected the difference between conspecific and heterospecific males. This was tested by a short (15 minutes) exposure to another fish in an isolated part of the aquarium. Recognition was defined as the ‘difference in a particular behaviour between the two conditions’. What was monitored was the swimming behaviour and trajectory (1 image per second) together with known social behaviours of this genus. The selection of these behaviours was further facilitated based on experimental set-ups of reproductive behaviour or the same species previously described by the same research team (Kéver et al. 2018). The result was that O. nasuta females, for which it was expected that they would not hybridize, showed a different behaviour towards a con- or a heterospecific male. They interacted less with males of the other species. What was unexpected is that there was no difference in behaviour of the females whether they recognized a male or (control) female of their own species. This suggests that they did not detect differences in reproductive behaviour, but rather in the interactions between conspecifics. For females of O. ventralis, for which there are indications for hybridization in the wild, they did not find a difference in behaviour. Females of this species behaved identically with respect to the right and wrong males as well as towards the control females. Interestingly is thus that a complex pattern between species in the wild could be (partially) explained by the behaviour/interaction at first impression of the individuals of these species. References Kéver L, Parmentier E, Derycke S, Verheyen E, Snoeks J, Van Steenberge M, Poncin P (2018) Limited possibilities for prezygotic barriers in the reproductive behaviour of sympatric Ophthalmotilapia species (Teleostei, Cichlidae). Zoology, 126, 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zool.2017.12.001 Kocher TD (2004) Adaptive evolution and explosive speciation: the cichlid fish model. Nature Reviews Genetics, 5, 288–298. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg1316 Mendelson TC, Shaw KL (2012) The (mis)concept of species recognition. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 27, 421–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2012.04.001 Nevado B, Fazalova V, Backeljau T, Hanssens M, Verheyen E (2011) Repeated Unidirectional Introgression of Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA Between Four Congeneric Tanganyikan Cichlids. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 28, 2253–2267. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msr043 Salzburger W (2018) Understanding explosive diversification through cichlid fish genomics. Nature Reviews Genetics, 19, 705–717. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-018-0043-9 Seehausen O (2004) Hybridization and adaptive radiation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 19, 198–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2004.01.003 Steenberge MV, Jublier N, Kéver L, Gresham S, Derycke S, Snoeks J, Parmentier E, Poncin P, Verheyen E (2022) The initial response of females towards congeneric males matches the propensity to hybridise in Ophthalmotilapia. bioRxiv, 2021.08.07.455508, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.07.455508 | The initial response of females towards congeneric males matches the propensity to hybridise in Ophthalmotilapia | Maarten Van Steenberge, Noemie Jublier, Loic Kever, Sophie Gresham, Sofie Derycke, Jos Snoeks, Eric Parmentier, Pascal Poncin, Erik Verheyen | <p style="text-align: justify;">Cichlid radiations often harbour closely related species with overlapping niches and distribution ranges. Such species sometimes hybridise in nature, which raises the question how can they coexist. This also holds f... |  | Aquatic, Behavior, Evolution, Fish, Vertebrates, Veterinary entomology | Ellen Decaestecker | 2021-08-09 12:22:49 | View | |

08 Mar 2024

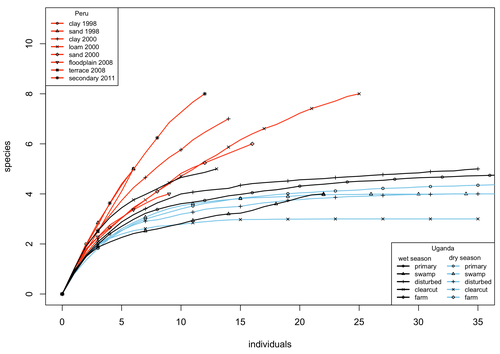

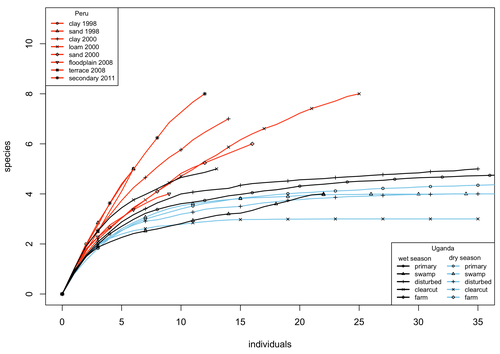

A comparison of the parasitoid wasp species richness of tropical forest sites in Peru and Uganda – subfamily Rhyssinae (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae)Tapani Hopkins, Hanna Tuomisto, Isrrael C. Gómez, Ilari E. Sääksjärvi https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.23.554460Two sides of tropical richness, parasitoid wasps collected by Malaise traps in tropical rainforests of South America and AfricaRecommended by Giovanny Fagua based on reviews by Mabel Alvarado, Filippo Di Giovanni and 2 anonymous reviewersInsect species richness and diversity comparisons between samples of the tropics around the world are rare, especially in taxa composed mainly of cryptic species as parasitoid wasps. The article by Hopkins et al. (2024) compares samples of parasitoid wasps of the subfamily Rhyssinae (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae) collected by Malaise traps in tropical rainforests of Perú and Uganda. The samples presented several differences in the time of collecting, covertures, and the sampling number; however, they used the same kind of traps, and the taxonomic process for species delimitation was made for the same team of ichneumonid experts, using equivalent characters. Publications about this kind of comparative study are difficult to find because cooperative projects on insect richness and diversity from South American and African continents are not frequent. In this sense, this study presented a valuable contrast that shows interesting results about the higher richness and lower abundance of the biota of the American tropics, even with a small sample, in comparison with the biota of the African tropics. The results are supported mainly by the rarefaction curves shown. This pattern of higher species richness and lower specimen abundance, observed in other American tropical taxa such as trees, birds, or butterflies, is observed too in these parasitoid wasps, increasing the body of information that could support the extension of the pattern to the entire biota of the American tropics. The authors recognize the study's limitations, which include strong differences in the size of the forest coverture between places. However, these differences and others are enough described and discussed. This work is useful because it increases the information about the diversity patterns of the tropics around the world and because study a taxon mainly composed of cryptic species, with a small amount of information in tropical regions. References Hopkins T., Tuomisto H., Gómez I.C., Sääksjärvi I. E. 2024. A comparison of the parasitoid wasp species richness of tropical forest sites in Peru and Uganda – subfamily Rhyssinae (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae). bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.23.554460 | A comparison of the parasitoid wasp species richness of tropical forest sites in Peru and Uganda – subfamily Rhyssinae (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae) | Tapani Hopkins, Hanna Tuomisto, Isrrael C. Gómez, Ilari E. Sääksjärvi | <p style="text-align: justify;">The global distribution of parasitoid wasp species richness is poorly known. Past attempts to compare data from different sites have been hampered by small sample sizes and lack of standardisation. During the past d... |  | Biodiversity, Biogeography, Insecta | Giovanny Fagua | 2023-08-24 18:30:26 | View | |

14 Nov 2023

Time-course of antipredator behavioral changes induced by the helminth Pomphorhynchus laevis in its intermediate host Gammarus pulex: the switch in manipulation according to parasite developmental stage differs between behaviorsThierry Rigaud, Aude Balourdet, Alexandre Bauer https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.25.538244Exploring manipulative strategies of a trophically-transmitted parasite across its ontogenyRecommended by Thierry Lefevre based on reviews by Adèle Mennerat and 1 anonymous reviewerThe intricate relationships between parasites and their hosts often involve a choreography of behavioral changes, with parasites manipulating their hosts in a way that enhances - or seemingly enhances – their transmission (Hughes et al., 2012; Moore, 2002; Poulin, 2010). Host manipulation is increasingly acknowledged as a pervasive adaptive transmission strategy employed by parasites, and as such is one of the most remarkable manifestations of the extended phenotype (Dawkins, 1982). In this laboratory study, Rigaud et al. (2023) delved into the time course of antipredator behavioral modifications induced by the acanthocephalan Pomphorhynchus laevis in its amphipod intermediate host Gammarus pulex. This system has a good foundation of prior knowledge (Bakker et al., 2017; Fayard et al., 2020; Perrot-Minnot et al., 2023), nicely drawn upon for the present work. This parasite orchestrates a switch from predation suppression, during the noninfective phase, to predation enhancement upon maturation. Specifically, G. pulex infected with the non-infective acanthella stage of the parasite can exhibit increased refuge use and reduced activity compared to uninfected individuals (Dianne et al., 2011, 2014), leading to decreased predation by trout (Dianne et al., 2011). In contrast, upon reaching the infective cystacanth stage, the parasite can enhance the susceptibility of its host to trout predation (Dianne et al., 2011). The present work aimed to understand the temporal sequence of these behavioral changes across the entire ontogeny of the parasite. The results confirmed the protective role of P. laevis during the acanthella stage, wherein infected amphipods exhibited heightened refuge use. This protective manipulation, however, became significant only later in the parasite's ontogeny, suggesting a delayed investment strategy, possibly influenced by the extended developmental time of P. laevis. The protective component wanes upon reaching the cystacanth stage, transitioning into an exposure strategy, aligning with theoretical predictions and previous empirical work (Dianne et al., 2011; Parker et al., 2009). The switch was behavior-specific. Unlike the protective behavior, a decline in the amphipod activity rate manifested early in the acanthella stage and persisted throughout development, suggesting potential benefits of reduced activity for the parasite across multiple stages. Furthermore, the findings challenge previous assumptions regarding the condition-dependency of manipulation, revealing that the parasite-induced behavioral changes predominantly occurred in the presence of cues signaling potential predators. Finally, while amphipods infected with acanthella stages displayed survival rates comparable to their uninfected counterparts, increased mortality was observed in those infected with cystacanth stages. Understanding the temporal sequence of host behavioral changes is crucial for deciphering whether it is adaptive to the parasite or not. This study stands out for its meticulous examination of multiple behaviors over the entire ontogeny of the parasite highlighting the complexity and condition-dependent nature of manipulation. The protective-then-expose strategy emerges as a dynamic process, finely tuned to the developmental stages of the parasite and the ecological challenges faced by the host. The delayed emergence of protective behaviors suggests a strategic investment by the parasite, with implications for the host's survival and the parasite's transmission success. The differential impact of infection on refuge use and activity rate further emphasizes the need for a multidimensional approach in studying parasitic manipulation (Fayard et al., 2020). This complexity demands further exploration, particularly in deciphering how trophically-transmitted parasites shape the behavioral landscape of their intermediate hosts and its temporal dynamic (Herbison, 2017; Perrot-Minnot & Cézilly, 2013). As we discover the many subtleties of these parasitic manipulations, new avenues of research are unfolding, promising a deeper understanding of the ecology and evolution of host-parasite interactions. References Bakker, T. C. M., Frommen, J. G., & Thünken, T. (2017). Adaptive parasitic manipulation as exemplified by acanthocephalans. Ethology, 123(11), 779–784. https://doi.org/10.1111/eth.12660 Dawkins, R. (1982). The extended phenotype: The long reach of the gene (Reprinted). Oxford University Press. Dianne, L., Perrot-Minnot, M.-J., Bauer, A., Gaillard, M., Léger, E., & Rigaud, T. (2011). Protection first then facilitation: A manipulative parasite modulates the vulnerability to predation of its intermediate host according to its own developmental stage. Evolution, 65(9), 2692–2698. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01330.x Dianne, L., Perrot-Minnot, M.-J., Bauer, A., Guvenatam, A., & Rigaud, T. (2014). Parasite-induced alteration of plastic response to predation threat: Increased refuge use but lower food intake in Gammarus pulex infected with the acanothocephalan Pomphorhynchus laevis. International Journal for Parasitology, 44(3–4), 211–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2013.11.001 Fayard, M., Dechaume‐Moncharmont, F., Wattier, R., & Perrot‐Minnot, M. (2020). Magnitude and direction of parasite‐induced phenotypic alterations: A meta‐analysis in acanthocephalans. Biological Reviews, 95(5), 1233–1251. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12606 Herbison, R. E. H. (2017). Lessons in Mind Control: Trends in Research on the Molecular Mechanisms behind Parasite-Host Behavioral Manipulation. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 5, 102. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2017.00102 Hughes, D. P., Brodeur, J., & Thomas, F. (2012). Host manipulation by parasites. Oxford university press. Moore, J. (2002). Parasites and the behavior of animals. Oxford University Press. Parker, G. A., Ball, M. A., Chubb, J. C., Hammerschmidt, K., & Milinski, M. (2009). When should a trophically transmitted parasite manipulate its host? Evolution, 63(2), 448–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00565.x Perrot-Minnot, M.-J., & Cézilly, F. (2013). Investigating candidate neuromodulatory systems underlying parasitic manipulation: Concepts, limitations and prospects. Journal of Experimental Biology, 216(1), 134–141. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.074146 Perrot-Minnot, M.-J., Cozzarolo, C.-S., Amin, O., Barčák, D., Bauer, A., Filipović Marijić, V., García-Varela, M., Servando Hernández-Orts, J., Yen Le, T. T., Nachev, M., Orosová, M., Rigaud, T., Šariri, S., Wattier, R., Reyda, F., & Sures, B. (2023). Hooking the scientific community on thorny-headed worms: Interesting and exciting facts, knowledge gaps and perspectives for research directions on Acanthocephala. Parasite, 30, 23. https://doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2023026 Poulin, R. (2010). Parasite Manipulation of Host Behavior. In Advances in the Study of Behavior (Vol. 41, pp. 151–186). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-3454(10)41005-0 Rigaud, T., Balourdet, A., & Bauer, A. (2023). Time-course of antipredator behavioral changes induced by the helminth Pomphorhynchus laevis in its intermediate host Gammarus pulex: The switch in manipulation according to parasite developmental stage differs between behaviors. bioRxiv, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Zoology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.25.538244 | Time-course of antipredator behavioral changes induced by the helminth *Pomphorhynchus laevis* in its intermediate host *Gammarus pulex*: the switch in manipulation according to parasite developmental stage differs between behaviors | Thierry Rigaud, Aude Balourdet, Alexandre Bauer | <p style="text-align: justify;">Many trophically transmitted parasites with complex life cycles manipulate their intermediate host antipredatory defenses in ways facilitating their transmission to final host by predation. Some parasites also prote... |  | Aquatic, Behavior, Crustacea, Invertebrates, Parasitology | Thierry Lefevre | 2023-06-20 15:49:32 | View | |

21 Jun 2023

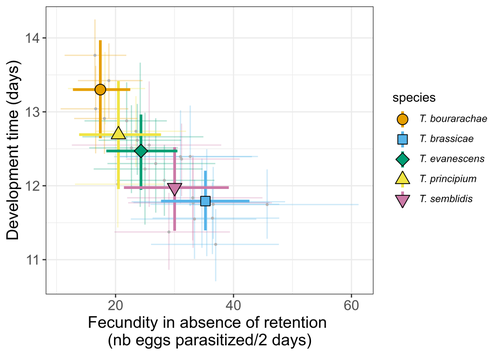

Life-history traits, pace of life and dispersal among and within five species of Trichogramma wasps: a comparative analysisChloé Guicharnaud, Géraldine Groussier, Erwan Beranger, Laurent Lamy, Elodie Vercken, Maxime Dahirel https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.24.525360The relationship between dispersal and pace-of-life at different scalesRecommended by Jacques Deere based on reviews by Mélanie Thierry and 1 anonymous reviewerThe sorting of organisms along a fast-slow continuum through correlations between life history traits is a long-standing framework (Stearns 1983) and corresponds to the pace-of-life axis. This axis represents the variation in a continuum of life-history strategies, from fast-reproducing short-lived species to slow-reproducing long-lived species. The pace-of-life axis has been the focus of much research largely in mammals, birds, reptiles and plants but less so in invertebrates (Salguero-Gómez et al. 2016; Araya-Ajoy et al. 2018; Healy et al. 2019; Bakewell et al. 2020). Outcomes from this research have highlighted variation across taxa on this axis and mixed support for, and against, patterns expected of the pace-of-life continuum. Given this, a greater understanding of the variation of the pace-of-life across-, and within, taxa are needed. Indeed, Guicharnard et al. (2023) highlight several points regarding our broader understanding of pace-of-life. In general, invertebrates are poorly represented, the variation of pace-of-life across taxonomic scales is less well understood and the relationship between pace-of-life and dispersal, a key life history, requires more attention. Here, Guicharnard et al. (2023) provide a first attempt at addressing the relationship between dispersal and pace-of-life at different scales. The authors, under controlled conditions, investigated how life-history traits and effective dispersal covary for 28 lines from five species of endoparasitoid wasps from the genus Trichogramma. At the species level negative correlations were found between development time and fecundity, matching pace-of-life axis predictions. Although this correlation was not found to be significant among lines, within species, a similar pattern of a negative correlation was observed. This outcome matches previous findings that consistent pace-of-life axes become more difficult to find at lower taxonomic levels. Unlike the other life-history traits measured, effective dispersal showed no evidence of differences between species or between lines. The authors also found no correlation between effective dispersal and other-life history traits which suggests no dispersal/life-history syndromes in the species investigated. One aspect that was not assessed was the impact of density dependence on pace-of-life and effective dispersal, largely as this was a first step in assessing relationship of dispersal with pace-of-life at different scales. However, the authors do acknowledge the importance of future studies incorporating density dependence and that such studies could potentially lead to more generalizable understanding of pace-of-life and dispersal within Trichogramma. A pleasant addition was the link to potential implications for biocontrol. This addition showed an awareness by the authors of how insights into pace-of-life can have an applied component. The results of the study highlighted that selecting for specific lines of a species, to maximise a trait of interest at the cost of another, may not be as effective as selecting different species when implementing biocontrol. This is especially important as often single, established species used in biocontrol are favoured without consideration of the potential of other species which can lead to more efficient biocontrol. REFERENCES Araya-Ajoy, Y.G., Bolstad, G.H., Brommer, J., Careau, V., Dingemanse, N.J. & Wright, J. (2018). Demographic measures of an individual's "pace of life": fecundity rate, lifespan, generation time, or a composite variable? Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 72, 75. | Life-history traits, pace of life and dispersal among and within five species of *Trichogramma* wasps: a comparative analysis | Chloé Guicharnaud, Géraldine Groussier, Erwan Beranger, Laurent Lamy, Elodie Vercken, Maxime Dahirel | <p>Major traits defining the life history of organisms are often not independent from each other, with most of their variation aligning along key axes such as the pace-of-life axis. We can define a pace-of-life axis structuring reproduction and de... |  | Biology, Ecology, Insecta, Invertebrates, Life histories | Jacques Deere | 2023-01-25 18:15:20 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Dominique Adriaens

Ellen Decaestecker

Benoit Facon

Isabelle Schon

Emmanuel Toussaint

Bertanne Visser